I interrupt this nonexistent gubernatorial campaign for the following historical tidbit: It hasn’t always been like this.

Before radio and television caused people to stay home all the time, the two nominees for governor traveled together, conducting stump debates in as many as 56 towns along the way.

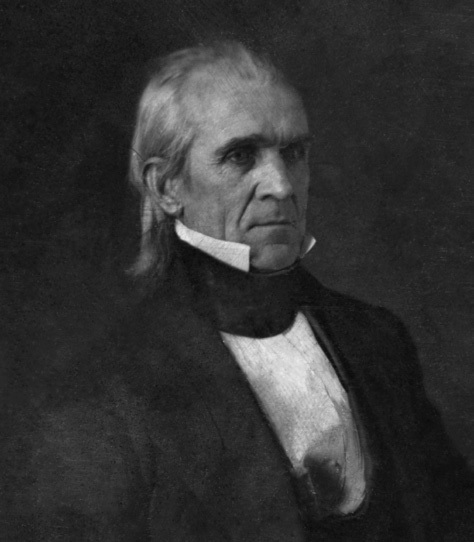

As best I can tell, we can thank James K. Polk for starting this tradition. In 1839 Polk ran against incumbent Gov. Newton Cannon and repeatedly asked his opponent to join him on his tour of the state. Cannon did so only a couple of times, which may have been why he lost to his young challenger.

When Polk ran for re-election two years later, his opponent was James C. Jones, a man so tall and slender that he was known as “Lean Jimmy.” Jones and Polk agreed on a 30-stop debate schedule.

The “gubernatorial canvass,” as it was known, started on June 7 in Shelbyville. From there the candidates migrated to Manchester, Salem (in Franklin County), Fayetteville, Pulaski, Lawrenceburg and the list went on and on through the rest of June, all of July and until Aug. 4, when they concluded at the Hamblen County community of Panther Springs.

Everyone expected Polk to win the debates, but that’s not exactly what happened. “Tall, unusually homely of features and spare, he (Jones) used his own lack of personal charms,” historian W.T. Hale said many years later. “He twisted Polk’s beautiful sentences into ridiculous jargon and successfully gave them a meaning entirely opposite to that intended.”

There are places in Tennessee where the Polk-Jones debates were the most important thing to have ever happened. Haywood County’s community of Dancyville, for instance, has a historical marker about the debate that occurred there on June 23, 1841.

“Lean Jimmy” won the 1841 election. The tour was so popular that the two men did an encore two years later when they were both renominated. This time, Jones and Polk started on May 26 and didn’t stop until July 31, visiting 47 towns in 66 days. That 1843 tour featured several communities that aren’t even incorporated today such as Harrison (Hamilton County), Washington (Rhea), Rheatown (Greene), Miller’s Store (Hawkins), Montgomery (Morgan) and Silver Springs (Wilson).

Jones also won the 1843 gubernatorial election, but (as a consolation prize) James K. Polk became president of the United States two years later.

The Polk-Jones debates started a tradition that stuck. In just about every election for the rest of the century, the two main candidates for governor toured together. Granted, there were times when this didn’t happen — the Civil War being one of those times — but it was expected by the electorate and the voters.

I want to remind everyone what it was like to travel in Tennessee in the mid-19th century. There were no planes, no cars and no well-paved roads. Railroads did start showing up in Tennessee in the 1850s, but many small towns didn’t have rail service as late as 1880. One took the public stagecoach, a private coach or a horse.

Meanwhile, the vast majority of towns in Tennessee had no hotels. It was not unusual for the candidates to have to share a bed and have meals together.

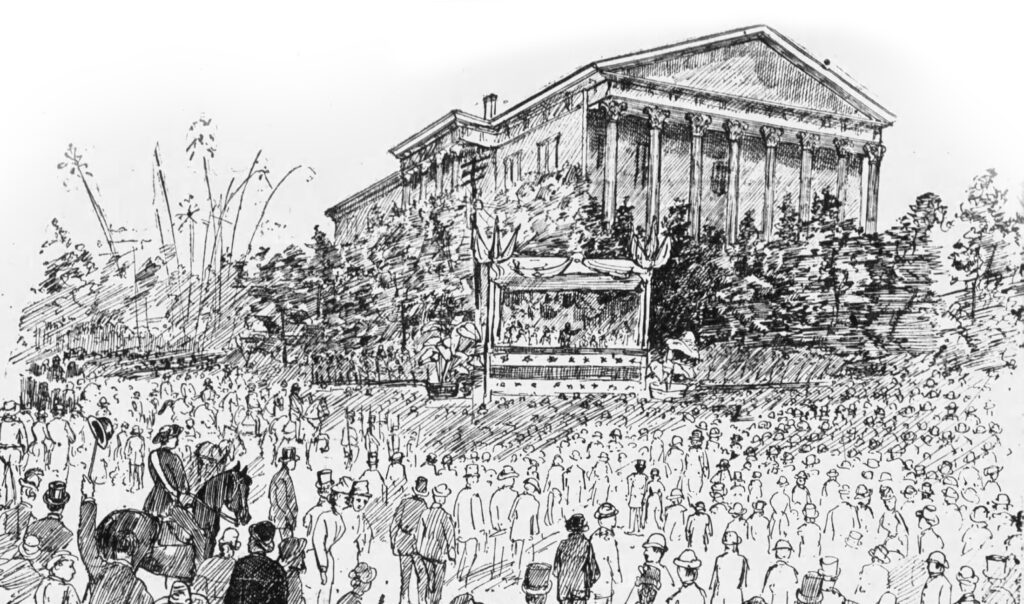

Speaking of tradition, debates never occurred on Sunday. When Isham Harris and Robert Hatton conducted a 53-town tour between May 25 and Aug. 3, 1857, they debated every day of the week except Sunday. The same thing happened on the 56-stop gubernatorial stump tour in 1880, the 47-stop tour in 1884, the 40-stop tour in 1898 and the 30-stop tour in 1904.

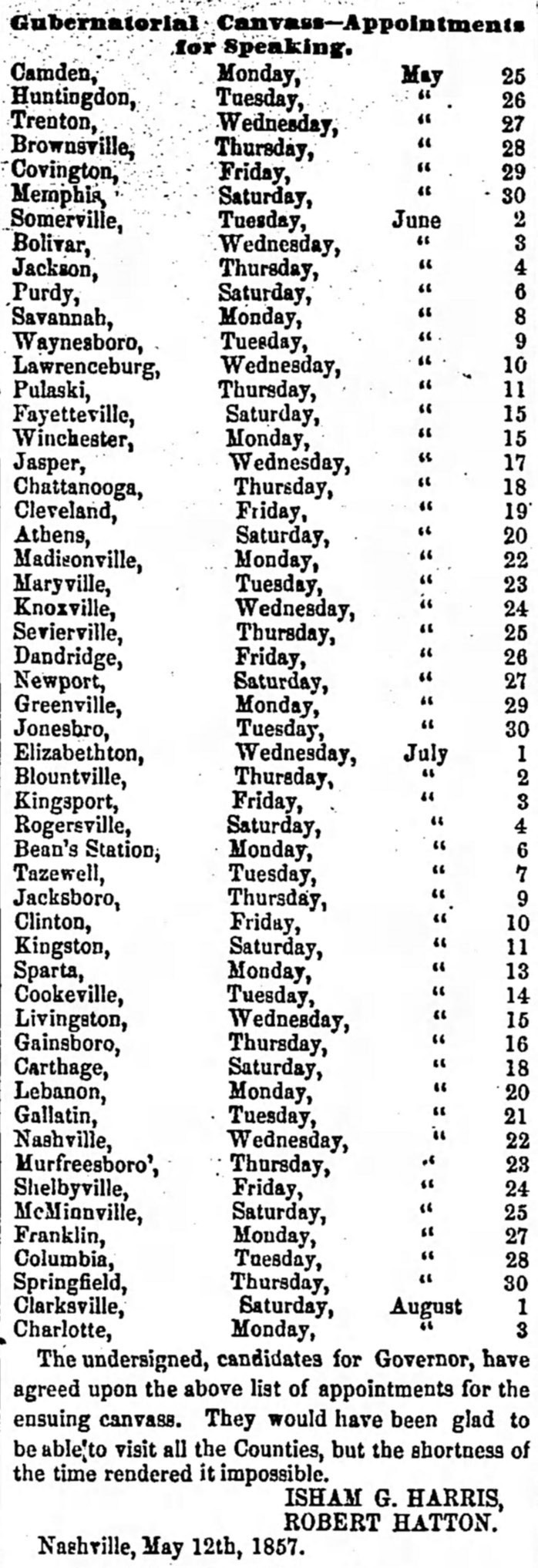

The most famous gubernatorial campaign in Tennessee history took place in 1886 when Democrat Robert Taylor ran against his brother, Republican Alfred Taylor. The very tone of this election was different than any other in history, with the two candidates playing fiddle on stage in between bits of humorous, lighthearted political banter. Since Robert wore a white rose and Albert wore a red rose, it became known as the “war of the roses” and made the cover of Harper’s Magazine.

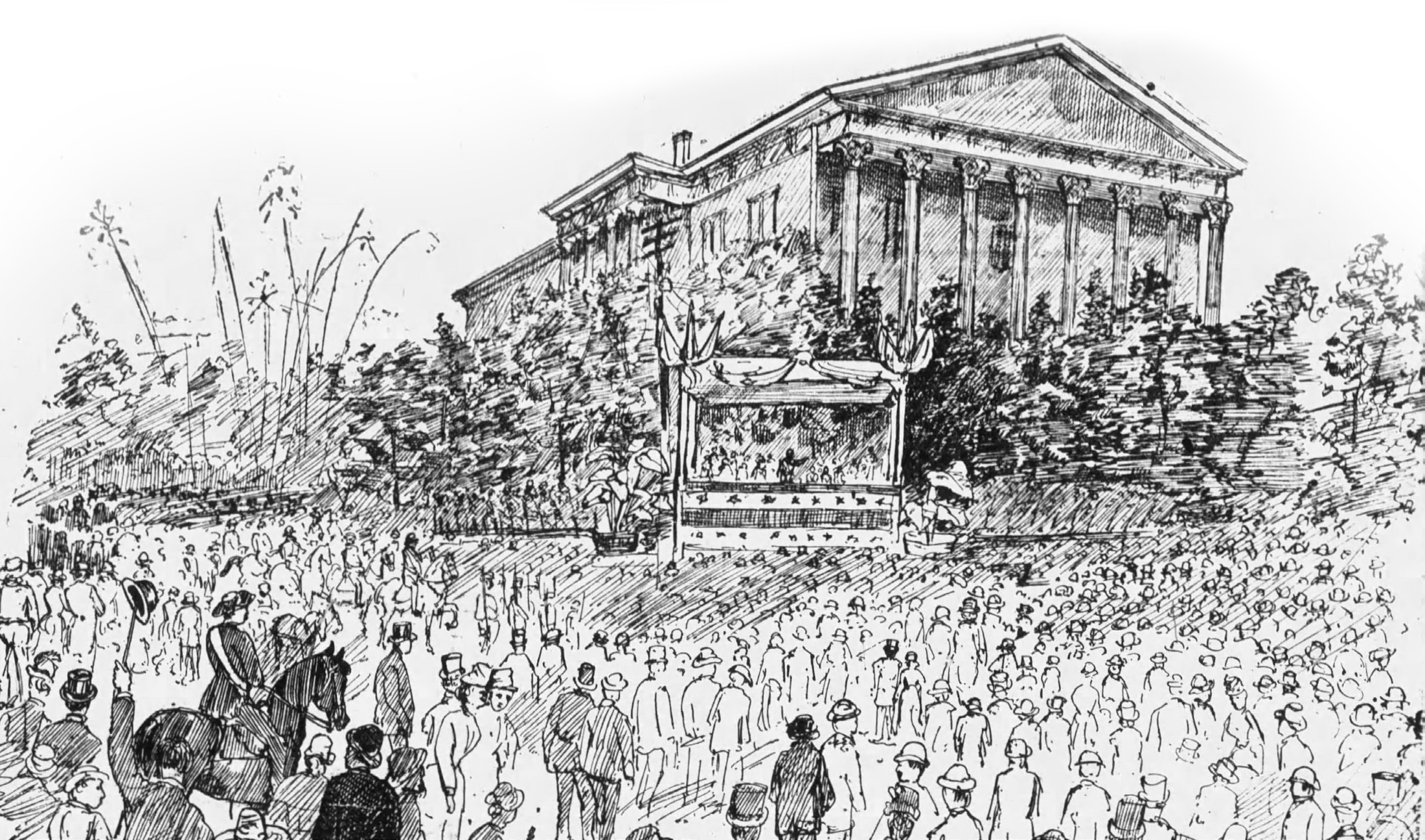

The road show arrived in Nashville on Monday, Oct. 18. Some 25,000 people turned out to see the brothers; there were parades, balloons and fireworks — but, unfortunately, no microphone. “Bob attempted to speak,” the Nashville American reported, “but the din of voices was so heavy that it was impossible to do so, and after a few minutes he bade the audience good night. No man could have addressed such a crowd, it was so large.”

So why did this remarkable Tennessee tradition end? In a word, animosity.

In 1908, plans were made for Edward Carmack and Malcolm Patterson to debate 41 times. However, the crowds were so badly behaved and the candidates so uncivil to each other that the events devolved into near riots. On May 1, things got so bad in Fayetteville that, according to the Chattanooga Star, “the candidates stood glowering at each other, about four feet apart, both trembling with excitement, while those seated on the platform jumped to their feet and begged both men not to engage in personal difficulty.” They might have come to blows right then were it not for the presence on the stage of 72-year-old Col. J.H. Holman, who served in the U.S. Army from 1857 to 1861 and the Confederate Army from 1861 to 1865. “Stop that right now!” Holman ordered the candidates, and they did.

The rest of the debates were called off; Patterson won the election. On Nov. 8, 1908, Carmack was shot and killed in Nashville by Duncan Cooper, a son of one of Patterson’s closest advisers.

I can find no evidence of a multitown gubernatorial canvass ever occurring in Tennessee after that time. There have been debates between candidates, of course, but only a small number each election — nothing like the 50-town stump tours of the 19th century.