In my view, the influenza epidemic of 1918 is the most overlooked event in American history. It killed up to 50 million people — possibly three times the number who died in World War I. Close to home, the epidemic killed about 8,000 Tennesseans.

In my view, the influenza epidemic of 1918 is the most overlooked event in American history. It killed up to 50 million people — possibly three times the number who died in World War I. Close to home, the epidemic killed about 8,000 Tennesseans.

Nearly everyone who was alive at that time had a story about how they lost a friend, a relative or a number of both. They remembered how schools were closed, churches were shut down and life was different. Quite a few of them recalled how they got sick and weren’t sure if they would survive.

And yet, you read almost nothing about the influenza epidemic in textbooks.

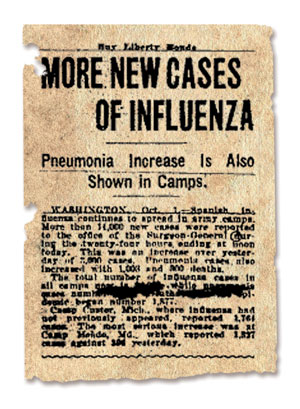

Medical historians are still trying to learn more about this virus. They believe it was strengthened by the large number of weak and malnourished people at the end of World War I and spread by millions of soldiers who came home at the end of that conflict.

Today, there is no consensus on the geographic origins of the outbreak. Some believe the virus originated in China, others say France and some believe Kansas. The epidemic didn’t just attack the weak, elderly and very young. It killed millions of previously healthy young adults as well.

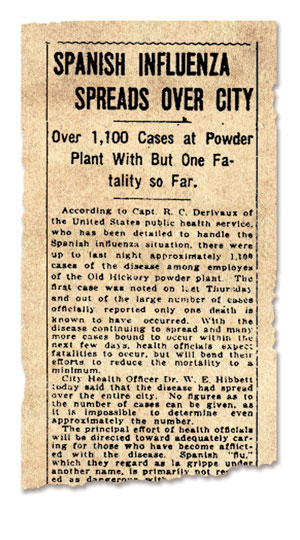

In Tennessee, the virus was most deadly in populated places like Memphis, Nashville and Old Hickory, a place in northeast Davidson County where a gunpowder plant was being constructed.

The disease was not confined to any one place, however. In Cumberland County, Dr. May Wharton could hardly keep up with the many cases of influenza at Pleasant Hill Academy. “On the first day five girls were laid low,” she wrote in her autobiography, “Doctor Woman of the Cumberlands.” “The next morning there were ten more. I put them in neighboring rooms.

“By the time the siege was at its height all but five of the fifty girls and six teachers were in bed.”

“By the time the siege was at its height all but five of the fifty girls and six teachers were in bed.”

Sixty miles east, in the Morgan County community of Coalfield, 98 percent of the 500 residents fell sick.

The University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine has created a website with scans of newspaper articles about the epidemic. Thanks to this site, one can easily access dozens of articles about it in the Nashville Banner and Nashville Tennessean.

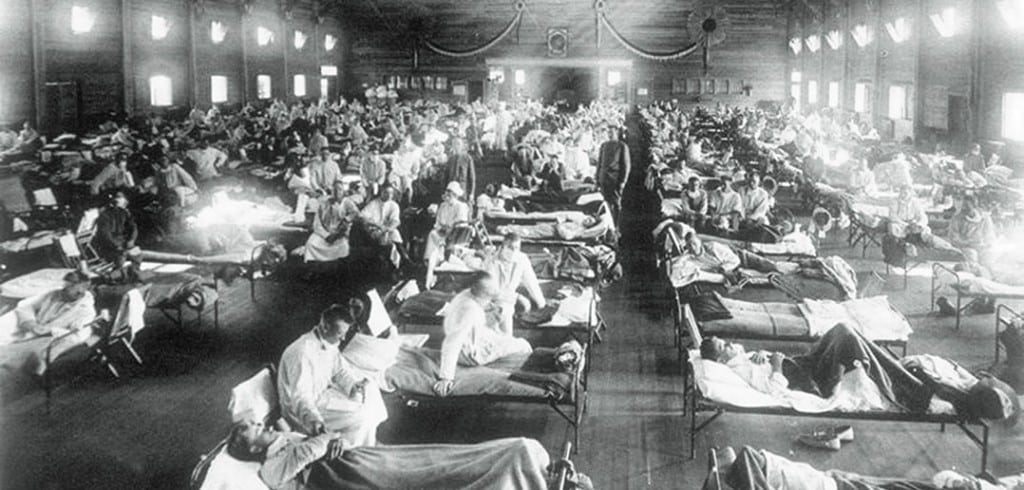

According to stories, the virus hit Nashville hard on Oct. 1, 1918. Within a few hours, the city hospital was overfilled. “A number of patients are in critical condition and will die, the disease being generally far more serious than previous epidemics of grip,” said Dr. Feasey of Nashville City Hospital. “Never before have we had to contend with as widespread an epidemic, and on account of the lack of accommodations, it is necessary for us to turn down calls.”

On Oct. 8, the Banner had three stories about influenza. In one, a local medical official is quoted as saying that “the spreading of hearsay stories” about the flu’s grim effects “will be promptly stopped, since there is no truth in them.” In the second story, the Nashville Board of Education announced that public schools would be shut down until further notice. In the third (and longest of all), it was reported that the surgeon general of the United States was sending eight additional doctors to Nashville to treat the sick.

“Theaters, picture shows, carnivals, dance halls, billiard and pool parlors were closed yesterday throughout the city by order of Dr. Hibbert (the city health officer),” the paper reported.

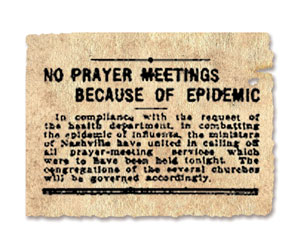

Five days later, the ministers of Nashville decided to stop holding services until further notice. For many of them, this was an easy decision because their sanctuaries had already been converted into hospitals for the sick and dying. “Pastors of the city request that members of their congregation hold family worship inside their homes,” it was reported.

By this time, public health officials estimated that there had been between 10,000 and 15,000 influenza cases in Nashville, 7,000 cases in Chattanooga and 1,500 in Knoxville. On Oct. 21, the Banner reported that Memphis had, so far, reported 278 fatalities from influenza, Nashville 266 and Knoxville 58.

By this time, public health officials estimated that there had been between 10,000 and 15,000 influenza cases in Nashville, 7,000 cases in Chattanooga and 1,500 in Knoxville. On Oct. 21, the Banner reported that Memphis had, so far, reported 278 fatalities from influenza, Nashville 266 and Knoxville 58.

As it turns out, those numbers appear to have been understatements. An article in the April 1978 Journal of the Tennessee Medical Association claims that the epidemic killed 435 people in Nashville alone in October 1918.

Reported cases of influenza decreased greatly in number by November. Around the first of that month, schools, churches, courts, movie theaters and other places were reopened. “Let us make it a great day of rejoicing that the pestilence is passing and that permanent peace is dawning,” suggested a Nov. 1 article in the Nashville Tennessean.

In smaller numbers, the epidemic continued for another year throughout the South. On July 14, 1919, Mr. and Mrs. O.B. Harris of Montgomery, Ala., had the great misfortune of losing two small children to the disease in the same day. “Death caused by stomach trouble claimed (2-year-old) Fred at 6:30 Monday morning, and (11-month-old) Mary Grace fell a victim to the same trouble at 4:30 Monday afternoon,” reported the Montgomery Advertiser.

The reason I know about this particular incident is that Mrs. O.B. Harris was my great aunt.

So why is the influenza epidemic overlooked? I have two theories, both related to World War I.

Catastrophic events that immediately follow wars have a tendency to be overlooked because historians are so focused on war. This explains why relatively few people know about the worst maritime disaster in American history (the explosion of the steamboat Sultana in 1865 near Memphis, which killed 1,700 people).

The other reason has to do with the media. In the fall of 1918, almost all newspapers in the United States and in Europe still had a form of wartime censorship in place. Bad news, including news about the epidemic, was intentionally being played down.

Today, we may not recognize the significance of this event, but that is not to say that it didn’t change world history. The influenza epidemic of 1918 marked a turning point in medical education and procedures. It created an impetus for the creation and expansion of hospitals in Tennessee and around the world.

In Nashville, for instance, the epidemic prompted civic leaders to start a new hospital in December 1918. That facility, originally Protestant Hospital and later named Baptist Hospital, is today a part of the St. Thomas chain.

Also, shortly after the epidemic, the Carnegie Foundation increased its donation to the new Vanderbilt Medical School from $1 million to $5 million. It was largely because of this money that Vanderbilt opened the first combined medical school and hospital in the United States in 1925.

There’s more on the Web

Go to tnhistoryforkids.org to learn more tales of Tennessee history.