A few weeks ago, I drove from Nashville to Knoxville and back on the same day to see my son for his birthday. It took about three hours each way, which was notable because it was raining and dark on the return drive.

I realize how impossible it would have been to pull off such a short round trip before Interstate 40 existed. So I thought I’d write a column about the history of I-40. Here are some things I’ve learned:

The general route Interstate 40 takes through Tennessee was tentatively laid out in a 1955 U.S. government document now known as the “Yellow Book.” After the plan was funded by Congress, it was up to civil engineers in each state to find the best places for interstates to cross rivers and mountain passes. It wasn’t until May 1959, for example, that it was decided that the split between I-40 and I-75 west of Knoxville would be at a place called Hope Gap, in Loudon County. Today, hundreds of thousands of people drive through Hope Gap on their way to and from Knoxville. I suspect that almost none of them know what the gap was once called.

Interstates got numerical identifiers in September 1957. It was then that the public learned that the superhighway connecting Memphis to Knoxville would be called Interstate 40.

When interstates were built, there were newspaper articles explaining that they would be “limited access” — a concept not everyone understood at the time. Also, the impact interstates would have on small-town downtowns was not fully understood when they were under construction. There were people who owned hotels near town squares who thought interstates would improve their business. They wouldn’t learn otherwise until the interstate opened and people started going to the brand-new Holiday Inn at the exit ramp.

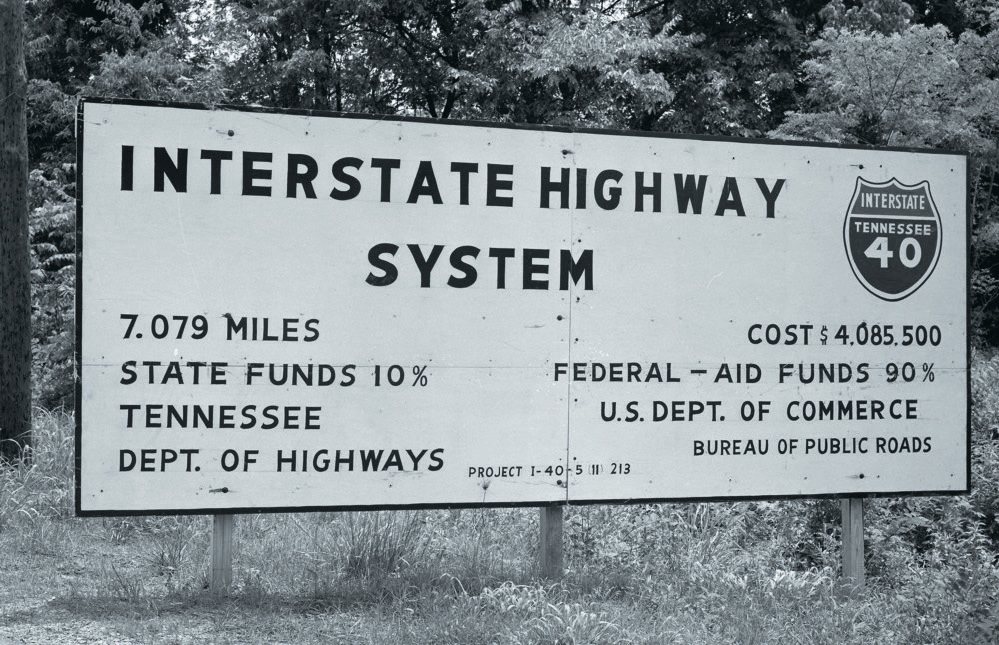

Interstates weren’t built by state governments, but by private contractors who graded, drained and paved segments of it along the way. In July 1958 alone, Tennessee bid out and awarded 53 interstate contracts to companies such as McDowell & McDowell Construction Co. of Nashville, Oman Construction of Nashville, J.B. Michael Construction of Memphis and Tillet Brothers Construction of Shelbyville. By 1960, more than 6,000 Tennessee residents were working on the new superhighways.

The first two segments of Interstate 40 to be opened were a 22-mile stretch near Jackson and a 35-mile stretch between Kingston and Knoxville — both of which were opened to traffic on Dec. 1, 1961. “The 35-mile Knoxville-Kingston Interstate stretch will definitely be opened to carry traffic for the Tennessee-Vanderbilt football game here Dec. 2,” reported the Knoxville News Sentinel. The next year saw the opening of 16 miles of I-40 in Putnam County, 19 miles in Cheatham and Williamson counties, and 9 miles in Haywood County.

It would be some time until Interstate 40 was completed all the way from Nashville to Knoxville. The various stretches of interstate in Nashville weren’t completed until about 1969 because there were so many property owners to be dealt with in the city. And, due to problematic terrain, it wouldn’t be until 1974 that the steep 9-mile stretch of I-40 between Cumberland County and Harriman was finished. “It has taken eight years to complete and stabilize the area, which transverses a geological fault that crosses the state from Kentucky to Alabama on the eastern slope of the Cumberland Mountains,” the Tennessean explained on Aug. 20, 1974.

Since it took so long to complete Interstate 40, drivers had to take a lot of steps when they planned trips that they don’t have to take now. During the era in which the interstate was being built, drivers had to read the newspaper, ask the gas station attendant along the way and/or obtain the highway map. It might have taken six hours to get from Nashville to Knoxville in 1960, five in 1965 and three in 1975.

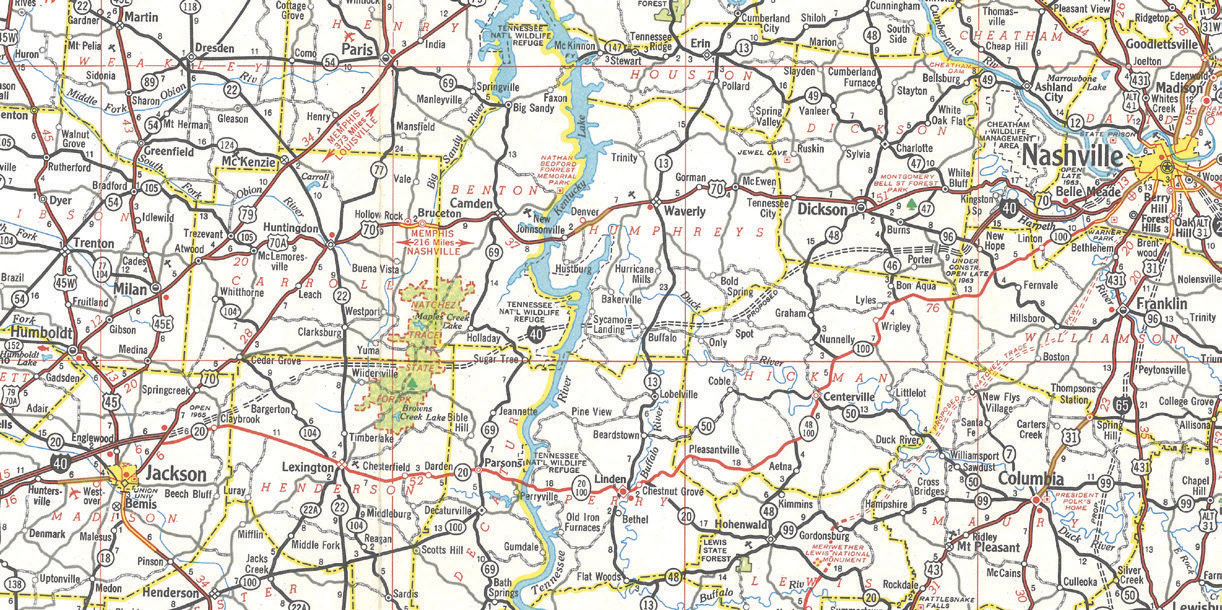

One way to document the completion of Tennessee’s interstate system is to look at old highway maps. The 1963 map shows only a segment here and there of I-40 open. The 1974 map shows Interstate 40 as mostly completed, other than a 17-mile stretch between Knoxville and Jefferson County.

The I-40 story in Memphis is a long one about which I devoted an entire column in 2018. The original plan called for the interstate to go through Overton Park. However, a grassroots organization called Citizens to Preserve Overton Park fought this proposal, citing a federal law that said the government could not run a highway through an existing public park unless there was “no feasible or prudent alternative to do so.” In 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the grassroots organization, but it wasn’t until 1981 that the Tennessee Department of Transportation gave up on the plan for I-40 to go through Overton Park. Because of this change of plans, Interstate 40 goes around Memphis instead of directly through it today.

When I-40 was built, there were no billboards along the way, and more than one person noted how beautiful the route was. “As one travels I-40, one of the most impressive features is its complete freedom from eye-soring signs and advertisements,” a Nashville Banner columnist wrote in February 1962. If you’ve driven I-40, you know that this didn’t remain the case for long.

Finally, here’s a somber discovery: The first person killed on I-40 (in Tennessee) was almost certainly 16-year-old Beth Harris. On Oct. 17, 1961, after a pep rally at Jackson High School in Madison County, Harris got into a car driven by another high school student. I-40 was paved in that part of the state but not yet opened to the public. The teenage driver ignored the “Do Not Enter” signs and floored the accelerator, according to the next day’s Jackson Sun.

Because the road was still being worked on, there was an eight-ton gravel spreader parked in the middle of the highway. By the time the driver saw it, it was too late. The convertible skidded 300 feet and crashed into the back of the gravel spreader — killing Beth Harris and injuring the driver.

Harris is buried in Jackson’s Hollywood Cemetery — about 4 miles south of Interstate 40.