There is nothing small about the talents of Wes and Rachelle Siegrist, whose artistic paths have been forged one little painting at a time.

Wes and Rachelle Siegrist of Townsend are award-winning miniature artists who have traveled the world painting, teaching and passing along the techniques of a unique art form. They first met in Florida in 1989 when Rachelle was Wes’ student. They were married the next year after Wes joked he would give her art lessons if she agreed to marry him. In short, she took him up on the offer, and the couple have been heart to heart — and elbow to elbow — painting together at their easels ever since.

The Siegrists have created their share of large-format paintings, but since the mid-1990s, they have focused almost exclusively on the beauty and discipline of miniature art as it’s been done since before the 15th century.

“We just love this way of painting,” says Wes, who, quite literally, wrote the book on miniature wildlife painting. His encyclopedic knowledge of the art form is demonstrated in “Modern Masters of Miniature Art in America,” and the Siegrists have co-authored “The World of Nature in Miniature” as well as a compilation of their own work, “Exquisite Miniatures.” These titles are all available at their website: artofwildlife.com.

“Miniature art quickly became a big part of who we are. It gets in your blood,” Rachelle says, sitting among the collection of tiny rocks and shells they have collected on their travels. An aquarium of guppies — countless guppies, each no larger than a quarter-inch in size — bubbles serenely in the corner of the room. Their delectation for the diminutive is represented everywhere.

Miniature painters were first employed as portrait artists long before the invention of photography. (See history on page 11.)

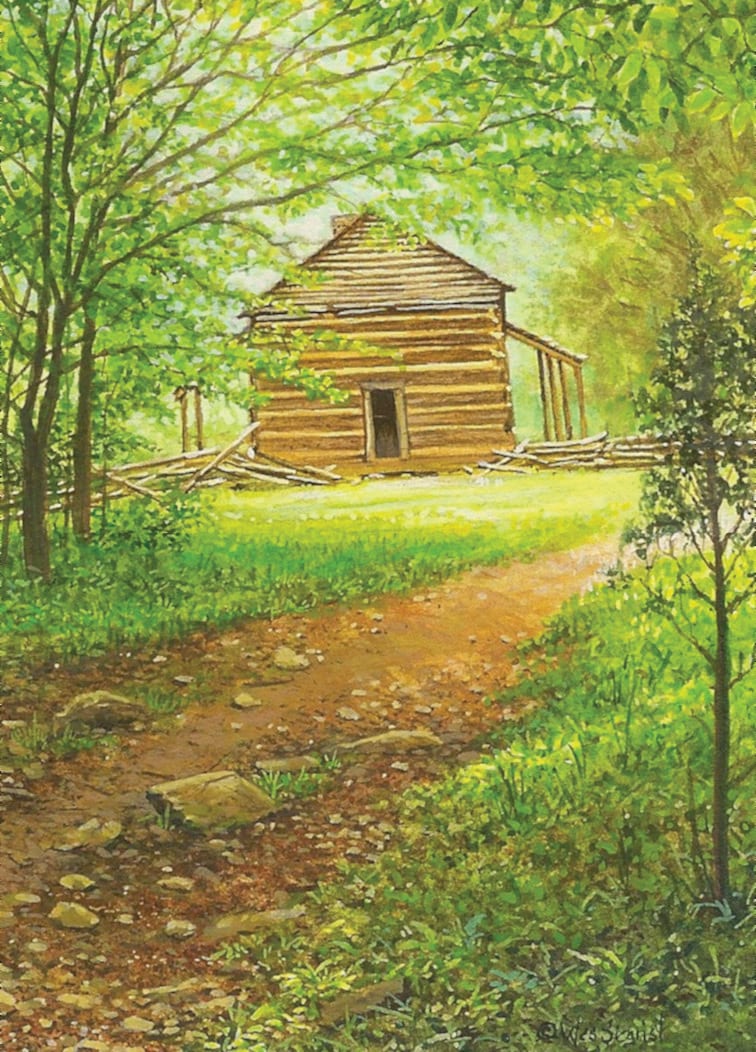

“Cabin in the Woods” by Wes Siegrist, 3.5 by 2.5 inches

These days, miniature painting has widened its scope to include more than just portraiture. It runs the gamut from landscapes to wildlife to still life — even abstracts. The Siegrists’ portfolios consist of all these things, with Rachelle’s known specialty at one time being pet portraiture. She has painted dozens of commissions of dogs, cats, horses, birds and other family pets — all on canvases 5 by 5 inches or smaller. Commissions, however, along with appearances at arts shows, have taken a very distant backseat as they’ve made the decision to focus on the handful of museum and gallery exhibits they participate in each year.

Being at the top of a very specialized field, the Siegrists are regularly presented with a variety of opportunities to showcase their work. “Several years ago,” says Rachelle, “we were asked by the Woolaroc Museum in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, to carry on the tradition of presidential portraits in miniature. They have a collection there of all the presidents in miniature. Wes did George W. Bush, and I did Obama and Trump. It’s a standing thing now. As long as we’re painting, we’ll add to their collection.”

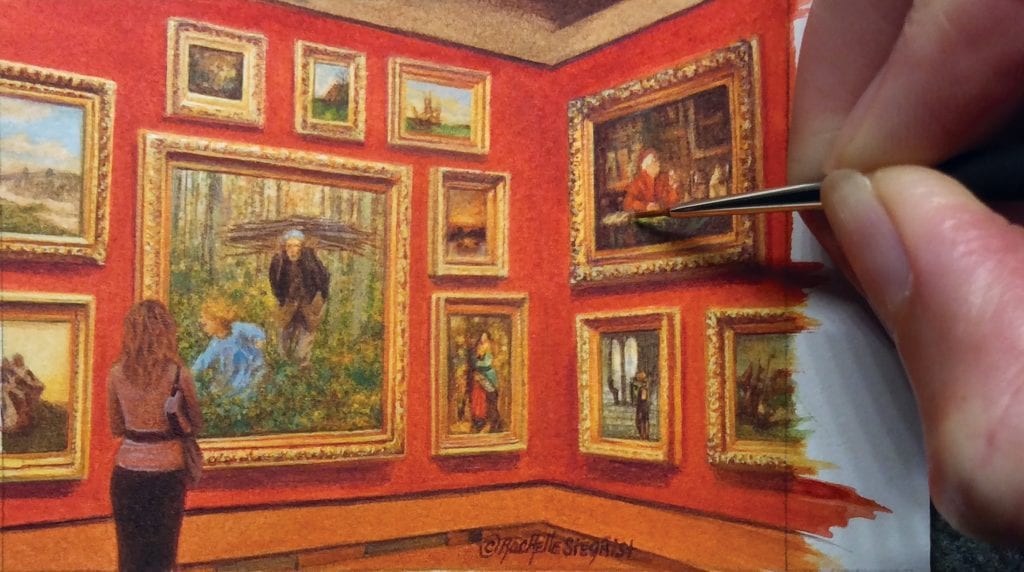

Rachelle Siegrist works on a 3.5-by-5-inch painting for an upcoming show.

Their studio combines as their office and is the size of a small bedroom. As one might imagine, when painting canvases 5 inches or smaller, there is little need for a large studio loft with massive easels and space to pace back and forth. The Siegrists sit facing a large window overlooking the deck just outside where squirrels and birds make themselves at home. Most artists want sunlight behind or above them, but the Siegrists prefer the window facing them as they work with magnifying glasses. The chance to gaze outside, they say, changes their focal length, basically giving their eyes a break.

The Siegrists say the desired result of all serious miniature artists is to emulate the quality and strength of a painting and showcase all the principles that make up good art — but to do it on a much smaller scale. Light and shadow, brushstrokes, texture, color — all things every artist learns in their training — are certainly no less important with miniature painting. One might argue they’re even more important, and it takes years to get accustomed to the tedium of working small, downsizing one’s brushes and canvas.

Wes Siegrist uses a razor blade to remove a particle of dirt from the paint surface of a 1-by-1-inch painting.

Watching the Siegrists work as they manipulate brushes the size of toothpicks — rendering the eye of a crocodile or the feathers of a bird — one realizes the great patience and discipline required to do what they do. There is a settled, almost zen-like quality to them as individuals, and it clearly reflects in the still, peacefulness of their work.

“Miniature art fans and collectors come to our exhibits with magnifying glasses,” says Wes, “so even a speck of dirt is visible if it gets into the paint. We are probably scrutinized to a higher degree than the other paintings that might be on exhibit.” Razor blades rest among their palettes and brushes and are used to scrape any imperfections from the surface of their paintings.

Rachelle says a square-inch painting will take her two to three days to complete while a larger one may take one to two weeks. Wes tends to work a bit faster. Depending on the size and complexity, the Siegrists’ miniature paintings sell at galleries for $600 to $2,000.

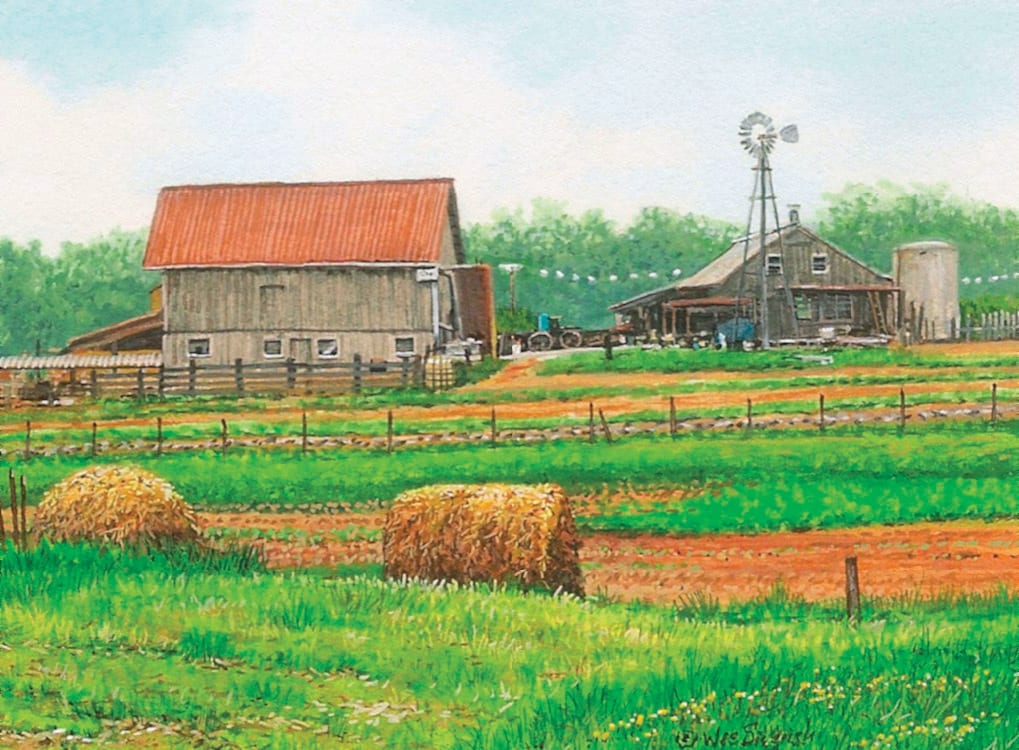

“A Tennessee Farmstead” by Wes Siegrist, 2.5 by 3.5 inches, shown here actual size.

Wes handles the business side of things, shouldering the financial and scheduling details, and last year began his busy tenure as executive director for the Society of Animal Artists. It’s a full-time job managing the career interests of hundreds of members worldwide.

When asked if miniature painting might soon see its extinction, Wes says, “Over time, our popularity has definitely gone in waves — up and down — and we are certainly at one of the bottom points of this current wave.” To further illustrate this point, he looks at his wife and smiles. “At 49 years old, Rachelle is the youngest member of the Miniature Artists of America society (the world’s only honor society of miniature art, based in Clearwater, Florida). She’s the kid.”

Rachelle nods. “That’s really sad to me,” she says. “There is no one younger who we can see to carry it on after we’ve gone.”

Wes agrees and says solemnly, “We might just be it.”

The Siegrists work in their tidy studio that doubles as office space where Wes organizes their gallery and tour schedule as well as his activities as executive director for the Society of Animal Artists. The couple have worked side by side since the early 1990s. They face an open window in order to give their eyes a rest by gazing outside frequently.

People of the 15th century surely never imagined the miracle of instant photography, let alone the smartphone cameras of our day, where images can be snapped, saved and pulled back up in seconds. A lot is changing in this fast-paced age of immediate gratification — but not everything.

It’s nice to know there are galleries, museums and entire societies of people around the world honoring artists who stubbornly, quietly refuse to take the easy way. They show us that art, wildlife and the natural world is worthy of our time and attention. And they remind us that great things do come in small packages. Sometimes it just takes a magnifying glass to find them.

“Stealthy Approach” by Rachelle Siegrist, 3.5 by 5.5 inches, shown here actual size. For more about the Siegrists, go to their website at artofwildlife.com or search for “The miniature paintings of Wes and Rachelle Siegrist” on Facebook.

The History of Miniature Painting

Portrait of an unknown woman by Christian Friedrich Zincke, 1716, courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

“Miniature portraits were always something for the wealthy gentry class,” says Wes Siegrist. “Even today, it is certainly a luxury item.”

Miniature portrait painting was an art form borne out of necessity by royals, military officers and on their travels, which could last many months at a time. The portraits were pulled out in quiet moments of homesickness when weary travelers needed to see a friendly face. Artists filled the demand for pocket-sized portraiture, trading in their large brushes and wall-sized canvases for this more demure and delicate form of expression and saw a boom that lasted more than 300 years.

Those artists passed it along to younger painters, training them to narrow their focus to the up-close and personal. They painted full-color portraits with tiny, custom brushes rendered on vellum, copper or ivory and fitted into lockets and onto the covers of snuff boxes. The frames of these impossibly small portraits — 1 to 3 inches, on average — had to be constructed by jewelers. That is largely still the case today.

Daguerreotype of Mary Ann Warren, 1850s, courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

By the 1700s, thousands of artists who painted in conventional scale also painted miniatures. The art form migrated from Europe and saw great popularity in the Americas as artists like Charles Peale shared their work in galleries across the colonies.

“Throughout history, almost all artists did miniatures,” explains Wes. “They’re what a lot of artists call ‘our bread-and-butter pieces,’ things that would pay our bills, not necessarily the ‘grand’ things. But that was obliterated almost overnight when photography got printed on paper and went to color.”

In the early 1800s, miniature artists felt the shock of technological progress with the advent of the daguerrotype, the first widely available photography made on silver-plated copper. A customer could step into a photography studio with a loved one and walk out minutes later with a sharp, lifelike image that was cheaper and less delicate than its labor-intensive predecessor. Over the next century, photography kept getting cheaper, faster and more portable, and the sales of miniature portraiture saw a dramatic decline.

See the Siegrists’ work up close in 2020

Society of Animal Artists’ 59th Annual Art & The Animal Tour One painting from each artist

Feb. 1–April 15

The Evelyn Burrow Museum, Hanceville, Alabama

May 22–Sept. 13

The Stamford Museum & Nature Center, Stamford, Connecticut

45th Annual International Miniature Art Show Seven paintings

Jan. 19–Feb. 9

Dunedin Fine Art Center, Dunedin, Florida

38th Southeastern Wildlife Exposition 45 paintings with artists in attendance

Feb. 12–16

Charleston, South Carolina

The Siegrists’ Exquisite Miniatures Touring Exhibition — 62 paintings

Jan. 25–April 26

Brookgreen Gardens, Murrells Inlet, South Carolina

(The Siegrists will be in attendance Jan. 24 and 25.)

May 15–Aug. 15

Shafer Art Gallery, Barton Community College, Great Bend, Kansas

Sept. 4–Nov. 4

The Art Center, Quincy, Illinois

Nov. 21, 2020–March 7, 2021

Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum, Chicago Academy of Science, Chicago