Chestnut trees face extinction unless measures are taken

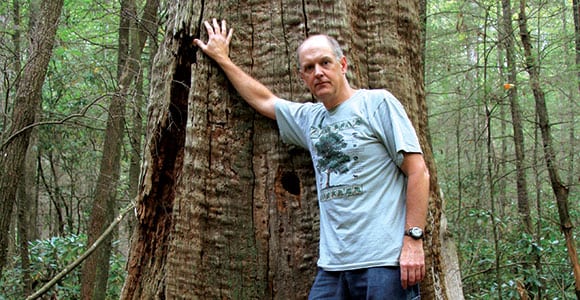

Dr. Gregory Weaver is too young to remember the American chestnut when it was the kingpin of trees — the most common and important tree in the eastern United States, a forest giant, often growing up to 100 feet tall and 5 feet in diameter. But chestnut blight, technically Cryphonectria parasitica, was accidentally imported from Asia, and by the end of the 1930s, the Tennessee chestnut forests were largely destroyed. Today, though, Weaver is one of the people determined to breed a blight-resistant cultivar of the American chestnut and return the tree to its rightful place as “king of the forest.”

Dr. Gregory Weaver is too young to remember the American chestnut when it was the kingpin of trees — the most common and important tree in the eastern United States, a forest giant, often growing up to 100 feet tall and 5 feet in diameter. But chestnut blight, technically Cryphonectria parasitica, was accidentally imported from Asia, and by the end of the 1930s, the Tennessee chestnut forests were largely destroyed. Today, though, Weaver is one of the people determined to breed a blight-resistant cultivar of the American chestnut and return the tree to its rightful place as “king of the forest.”

The tree earned its exalted title because of its many attributes.

“Chestnut trees grow all the way up to Canada,” Weaver says. “They are resistant to 30 degrees below zero and can tolerate 100-degree heat and go without rain. When harvested, chestnut wood is rot-resistant, lighter than oak but strong for its weight. It has a good combination of lightness, strength and rot-resistance. The chestnut also does not require the use of wood preservatives.”

In addition, the trees support wildlife from black bears to turkeys, songbirds, squirrels and chipmunks. The loss of chestnuts, a tasty and nutritious food source, is largely responsible for the 20th century decline in the number of black bears. Scientists don’t even know the full impact of the loss of the chestnut tree — considered one of the worst ecological disasters of the century — because ecological science was too primitive in the 1920s and ’30s. But, as Weaver notes, “You can’t erase 25 percent of a forest and not have an impact.”

A lifelong quest

Weaver’s journey to help restore the American chestnut actually began more than five decades ago, although he didn’t know it then. At the time, Weaver was just relishing Sunday afternoon walks on the family farm with his dad, Arles, mother Joyce and brothers Anthony and Tom.

“Daddy knew a lot about trees,” Weaver recalls, “and he would tell us about them. There were a lot of big chestnut stumps on the farm, and he would tell us stories about how important the chestnuts once were.

“Daddy remembered eating the nuts and how one of the signs of toughness as a young man was to stomp open the chestnut burrs with your bare feet. He could do it. Dad remembered watching the trees die, the tops dying first until they were just chestnut ghosts. Chestnuts are rot-resistant, though, so the trunks and stumps stood many years.”

Stumps were still scattered around the family farm when Greg left for college for a degree in forestry. He didn’t like the idea of cutting down trees, so that degree soon changed to premed followed by medical school and a specialty in radiology. Weaver never lost his love of forests and trees, though, most especially the chestnut.

In 1995, Weaver — by then a respected radiologist with a farm of his own — found a brochure about The American Chestnut Foundation (TACF) and the organization’s special breeding process. He joined immediately and went to its fall meeting.

“My knowledge of what was going on in regard to the chestnut was limited,” Weaver says. “I knew the history of the tree, but I didn’t know where the science was. I found out there were a wide assortment of people — scientists, academics, people like me, industrial foresters — who are serious about restoring the American chestnut. This wasn’t a theory. They were going to do this.”

Weaver is a doer. His idea of leisure is to haul rocks and build stately stone fences at the entrance to his farm on Leipers Creek Road just outside of Nashville. The goal of developing a stronger, blight-resistant strain of the tree intrigued him, although he knew prior attempts to breed blight-resistant trees in the mid-1900s were unsuccessful.

Weaver soon planted TACF-provided chestnut seeds on his farm.

“These were pure American chestnuts, so we knew they would get a blight infection and ultimately die,” he says, “but I needed to learn the proper technique of planting the trees and how to care for them. An intermediate step for my chestnut-growing efforts was to plant hybrids — trees that are partially blight-resistant and used to successively concentrate blight resistance in their offspring. A lot of my work has been to grow the generations of trees proximal to the ultimate goal.”

A recent addition to Weaver’s orchard are chestnut saplings that have already been crossbred. The trees — F3B3 chestnuts as they are known among TACF members — are 15/16 American chestnut and 1/16 Chinese chestnut.

“We want an American phenotype that is a forest canopy tree,” he says. “Before the blight, it was common for American chestnuts to be 120 feet tall when fully matured.”

But breeding a tree isn’t like other endeavors where you put the right ingredients together and create the product you desire. The breeding program has to go through six generations to reach the 15/16 American gene fraction, with the 1/16 for Chinese origin blight-resistance.

“Along the way you select American chestnut traits,” Weaver says. “Only about 8 percent are blight-resistant enough to propagate to the next generation. We’re still in testing. We will have to see how they grow.”

A microcosm of a bigger movement

Weaver can see some of that growth in his own chestnut orchard set high on a hill at his farm (chestnuts grow best on the top of hills). Each year, he has planted more trees.

“It’s important to keep planting,” Weaver says. “Some, the deer get; some, drought gets. Small rodents are a big problem. Voles, for instance, eat the plant roots and essentially amputate the trees. The aim is to increase the number over time.”

In this regard, Weaver says he and his fellow association members are farmers. “We’re growing a crop for a charitable cause and for future use, but we’re still farmers. We are subject to all the same problems that farmers are subject to.”

Drought is particularly rough on the trees, according to Weaver. He has designed a system to collect rainwater in huge barrels and then distribute it with hoses so the trees can be watered when there isn’t enough rain. The system can capture 13,000 gallons of rainwater and does not require electricity. It was a significant development because otherwise Weaver had to haul water in 5-gallon buckets a half a mile up the steep hill.

After years of protecting the seedlings from deer and other animals, keeping the young trees watered and building fences and watering systems, last summer members of the Tennessee chapter of The American Chestnut Association came to poison the very trees Weaver had worked so hard to grow.

They deliberately infected Weaver’s trees with two virulent strains of Cryphonectria parasitica. Then the trees were graded according to how they responded to the infection. Weaver said most of his trees were killed. “I have a few left,” he says, “and they will become parents for the next generation.”

This process is being duplicated across the nation. One of the leaders nationwide is the Hill Craddock, a professor at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga and one of the world’s pre-eminent chestnut scientists. Some 300 people in Tennessee and 6,000 nationwide are doing their part to help restore the tree.

In October, Weaver was honored for his work with a Volunteer Service Award from TACF. The award recognized his service as (past) president of the Tennessee chapter and his volunteer work growing an orchard, giving lectures and presentations and constructing an informational display about chestnuts that he made from recycled chestnut lumber. The display is currently on extended loan to the Science Department at Volunteer State Community College in Gallatin.

“This work is very important to me,” Weaver says, “but I am a small part of the total puzzle. We need everyone to volunteer, to do something. You don’t have to have a farm to participate. It is a huge commitment, and it is gratifying to see people across the spectrum pulling together.”

Now assisted by members and volunteers such as Weaver in 16 state chapters, TACF is planting restoration chestnuts in select locations throughout the eastern United States.

“My father’s generation saw chestnut trees in the forest,” Weaver says. “My generation is doing the work to get them back, but we won’t know if we were successful for 400 years. My hope is that my children will see the chestnuts introduced back into the forest.”

The website for the American Chestnut Foundation is www.acf.org. You can contact the Tennessee Chapter of TACF via email at lschibig@gmail.com.

Triumph from Tragedy

After the chestnut blight killed entire forests of trees, the trunks still stood tall for decades. In 1936, some farmers in Indiana decided to turn the tragedy into triumph, according to a December 2013 article in Rural Electric magazine. The farmers used the trunks to build an electric distribution system. Tall, strong and rot-resistant, the trunks were perfect poles, and soon, aided by a $100,000 loan from the Rural Electrification Administration, an electric cooperative was born and people who never had electricity before could now flip a switch and light their homes.

The first pole was set on Feb. 12, 1936. The last one was taken out of service in 1997. The American chestnut’s reputation for being strong and rot-resistant remained true even after the trees’ deaths.

These tree trunks were used as poles throughout the country. The trees were bought and sold in Tennessee and became an integral part of electrifying the nation.