There are abandoned iron furnaces — limestone monoliths ranging from 30 to 50 feet tall that cause passersby to stop and stare — all over Dickson, Stewart and Montgomery counties.

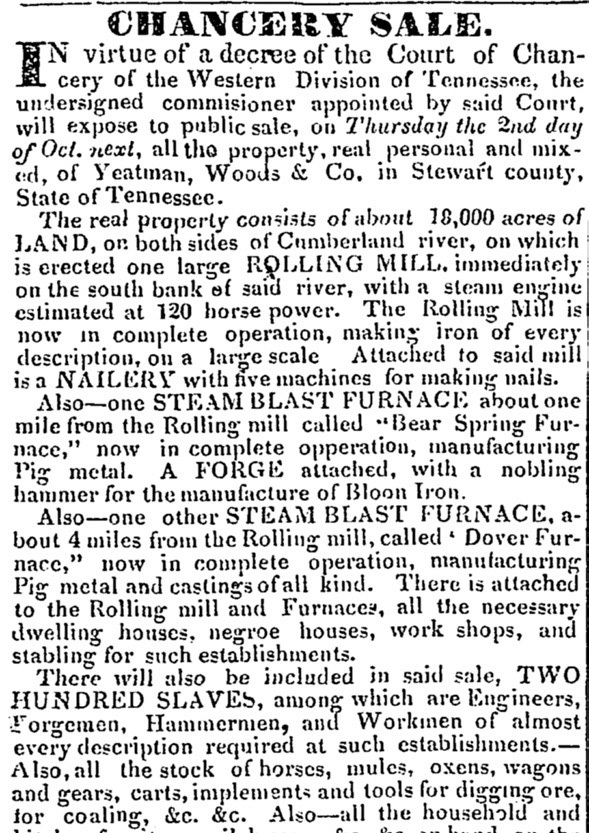

One of them is the Bear Spring Furnace. Just east of Dover, it sits in a rural part of a county in which, today, only about 1 percent of the residents are African American. And yet, in October 1834, because of the death of Thomas Yeatman, the entire industrial operation at Bear Spring Furnace was set to be auctioned — forge, factory, horses, wagons, 18,000 acres and no fewer than 200 enslaved people.

For years I’ve wondered who Yeatman was and how it is that the only remaining signs of him are few letters etched in stone.

In 1815, Yeatman ran a Nashville dry goods store that sold everything from cloth to spices to glassware — things people wanted but that had to be imported from far away. Like every other merchant of that era, Yeatman operated on credit. In the fall after harvest season, he’d ask his customers to settle their accounts. Then he’d make the long trip to Philadelphia where he’d order all the goods he intended to stock the next year. “Those persons indebted to the subscriber will please call at his store to settle their accounts, as he expects to start for Philadelphia in a few weeks,” he announced in a Nashville Whig ad in November 1816.

Yeatman made this trip every winter, making better contacts with merchants and bankers each time. On one of his buying trips, he learned there had been a sharp increase in the price of cotton. Yeatman sped home from Philadelphia, moving faster than the U.S. mail. (Remember, the telegraph did not exist yet.) Once he got home, he bought up all the cotton he could find in the warehouses of Middle Tennessee and north Alabama at 12.5 cents a pound, knowing it would be worth 25 cents a pound when it got to distant markets.

Yeatman made a lot of money on the cotton deal, but he didn’t stop there. He built a large warehouse beside the Cumberland River in Nashville where tobacco and cotton were stored before being loaded onto boats. He partnered with Joseph and Robert Woods and bought a steamboat, then a second, and then a third, which they renamed the Thomas Yeatman.

In 1825, the partners started a bank — Yeatman, Woods & Co. — which would remain one of the best-known financial institutions in the South for decades. (If you do a Google search, you’ll find images of its currency from the early 19th century.)

Thomas Yeatman loaned money for many ventures ranging from the Franklin Turnpike Company to the Nashville Water Works. He bought and sold paper currency. Although he was not a professional slave trader, he was a slaveholder who loaned money to other slaveholders so they could buy more slaves. His three steamboats would have been regularly commissioned to move enslaved people west and south as part of the interstate slave trade. In fact, an explosion on board the Thomas Yeatman killed half a dozen enslaved men in 1833.

The Thomas Yeatman was also one of the steamboats hired by the U.S. government to move Cherokee and Choctaw west during the Trail of Tears.

In the early 1800s, the most important industry on the Highland Rim was iron — separating ore into pig iron, then shaping it into nails, horseshoes, kitchen appliances, wagon axles and other products. These iron furnaces required thousands of acres and hundreds of people to tend fires and haul rock, firewood and finished product. It was difficult, hot work, and a lot of it was done by slaves.

In 1830 Yeatman, Woods & Co. bought Dickson County’s Cumberland Iron Works. The firm then built another big operation in Stewart County east of Dover. By 1833, Bear Spring Furnace produced 2,000 tons of rolled iron and 4,000 kegs of nails.

But on June 12, 1833, at the age of 45, Thomas Yeatman died of cholera on a steamboat bound for Philadelphia. The legal process of settling his estate led to plans being made for the Bear Spring operation to be auctioned in October 1834.

As it turns out, outsiders did not take over ownership of the Bear Spring Furnace; Yeatman’s sons and remaining partners simply shifted their ownership percentages. In 1843 the firm expanded and changed its name to Woods, Yeatman & Co. By the time the Civil War began, the business owned nearly 60,000 acres and more than 400 slaves.

Only 6 miles separated the Bear Spring Furnace from Fort Donelson, and the U.S. Army destroyed much of the iron smelting operation in the weeks after the 1862 battle at the fort. However, the owners resumed the operation after the war and built the limestone furnace that still stands on Highway 49 in Stewart County. But in the late 1870s, a sharp decline in iron prices soured the outlook for the industry. In 1878 the business sold 14,000 acres, but some version of the operation remained until around World War I.

Reading the complicated story of Yeatman, Woods and the Bear Spring Furnace might make you overlook that each enslaved person who showed up on the company balance sheets was a human being. But here’s a troubling anecdote from the history of the Highland Rim: In 1856, there was a rebellion among the thousands of enslaved people who worked in the iron industry in Montgomery, Dickson and Stewart counties. Although the extent of the insurrection was exaggerated in the press (as such rebellions typically were in that era), six of the enslaved were executed for their alleged roles in the insurrection.

Among the condemned were some of the enslaved held by U.S. Sen. John Bell of Tennessee. Bell had acquired those slaves two decades earlier when he married Thomas Yeatman’s widow, Jane Eakin Yeatman.