Fisk interviews reveal accurate details of our disturbing history

What was slavery in Tennessee really like? We do have some idea, as it turns out, in part because of a Fisk University researcher named Ophelia Settle Egypt.

In the late 1920s, Egypt interviewed Tennesseans who had been slaves prior to the Civil War. Her work, directed by a Fisk professor named Charles S. Johnson, may have inspired a similar but much larger project the federal government conducted between 1936 and 1938 (today known as the “slave narratives”). However, unlike the federal writer’s project, transcripts of the Fisk slave interviews were never widely circulated.

About a year ago, I bought a rare early edition of Egypt’s interviews titled “Unwritten History of Slavery.” The manuscript was printed by typewriter, only has text on one side of each page and is missing 26 pages. However, I can assure you that the 28 interviews transcribed in it are legitimate, priceless and paint a horrifying picture of slavery.

They are not, however, easy to comprehend. For some reason, Ophelia Egypt did not reveal the names of some of the people she interviewed (at least not in this rough draft). The people she interviewed were very old, never received much in the way of formal education and drifted from subject to subject. They also often didn’t make clear distinctions among events they saw and heard for themselves and those they learned about second hand. Furthermore, like many people of that generation, the interviewees frequently refer to slaves using the “N” word, which I will not quote in this column.

Here are summaries of what I considered to be the four best interviews: One man (name never revealed) said he was born in 1843 and had been a slave in Missouri, Mississippi and Tennessee. Like several of the interviewees, this man said his natural father was also his original slaveholder. “I was sold four times in my life,” he said, “the first time by my half-brother.”

This former slave went on to say that at one of the auction houses in which he had been sold, “You could see the women crying about their babies and children they had left.” He also recalled being transported from Missouri to Louisville via riverboat during a winter in which the Ohio River froze. This struck me as implausible, so I looked it up. Sure enough, the Ohio River froze in 1856.

One thing that makes this interviewee fascinating is his recollection of Nashville geography. The unnamed man, interviewed in the late 1920s, recalled the locations of Fort Gillem (present-day site of Fisk University) and the African-American institution known as Roger Williams University (present-day site of Vanderbilt’s Peabody campus.) “They (the Roger Williams administration) bought a place on Hillsboro Pike, right opposite Vanderbilt, and built a large building there,” he said. “It got burned down for some reason, and the white folks would not let them build it back.”

This summary of events is fairly accurate, as I retold in my July 2012 column.The interviewee also remembered (precisely) the location of Nashville’s main slave auction house: “right where the Morris Memorial Building is,” he said, referring to the headquarters of the National Baptist Convention at 330 Charlotte Avenue. “There was a sale block where they carried the Negroes there and auctioned them off. Right where that old building is now, those Irishmen got rich selling Negroes to white folks.”

Another man said he was born as a slave on a White County farm that had about eight slaves, including his mother, sister, aunt and uncle. What made this man interesting to me was that he enlisted in the U.S. Army after the Emancipation Proclamation. “I was in the Civil War for 22 months,” he said. “I went in when I was 17. I was with Company B, 42nd Colored Regiment.” However, he downplayed what he did in the war. “We wasn’t in no real fighting,” he said. “We would come to a place and see that nobody would come on it,” an accurate summary of guard duty, I thought.

I looked it up. Sure enough, the 42nd Colored Regiment existed from April 1864 to January 1866 and never saw combat, spending its time in garrison duty in Chattanooga.

With evidence of the man’s credibility, I went back and reread his interview, paying closer attention to some of his general comments about slavery. When asked about slaves who tried to learn how to read, he said that slaveholders “did-n’t want us to look at a book. (They) didn’t want us to know a thing.” In regards to physical abuse, he said slaveholders “wouldn’t whip horses half as hard” as they would whip slaves.

Susanna, one of the women interviewed, was born in 1858 to free black parents who lived near Nashville’s Public Square. In her interview, Susanna explained how her grandfather in the 1830s purchased not only his own freedom but that of his wife, Catherine, and daughter as well. “His white folks hired him to the Nashville Inn,” she said, referring to a long-standing hotel near the Davidson County courthouse. “Every Saturday, he would make about $5 or $10, and he would give to them (his slaveholders).

“He worked and worked, till I guess he paid them about $800 in all for himself. Then, one day, they sent for him and they said, ‘Well, Hardy, you are a free man; you can go anywhere you please, but you can’t take Catherine.’ Well, he was just like any other man, he wanted Catherine with him, so he turned ’round, and the white folks made him pay the same for Grandma.”

Susanna said her grandfather then saved enough money to buy his 3-year-old daughter (Susanna’s mother). “Finally they charged him, now mind you, for his own child, they charged him $350.”

A woman whose first name was Cornelia said she had been brought up as a slave in “Eden,” which I eventually discovered (by her reference to other locations) was the Gibson County community of Eaton. Cornelia said she and her family were the slaves of a man named Jennings. She said that, as slaves, her father worked as a “yardman, houseman, plowman, gardener, blacksmith, carpenter, keysmith” and “anything else they chose him to be,” while her mother “cooked, washed, ironed, spun, nursed and labored in the field.”

Her mother, however, was not an ideal slave because (in Cornelia’s words) she was “high spirited and independent.” This trait manifested itself one day when her mother got in a physical fight with Jennings’ wife, an event that led the family to send Cornelia’s parents away to work in Memphis.

Seven decades after the event, Cornelia remembered vividly the day Mr. Jennings took her parents to Memphis. “I cannot tell in words the feelings I had at that time,” she said. “My sorrow knew no bound. My very soul seemed to cry out, ‘gone, gone, gone forever.’ I cried until my eyes looked like balls of fire. I felt for the first time in my life that I had been abused. How cruel it was to take my mother and father away from me, I thought.

“My mother had been right. Slavery was cruel, so very cruel.”

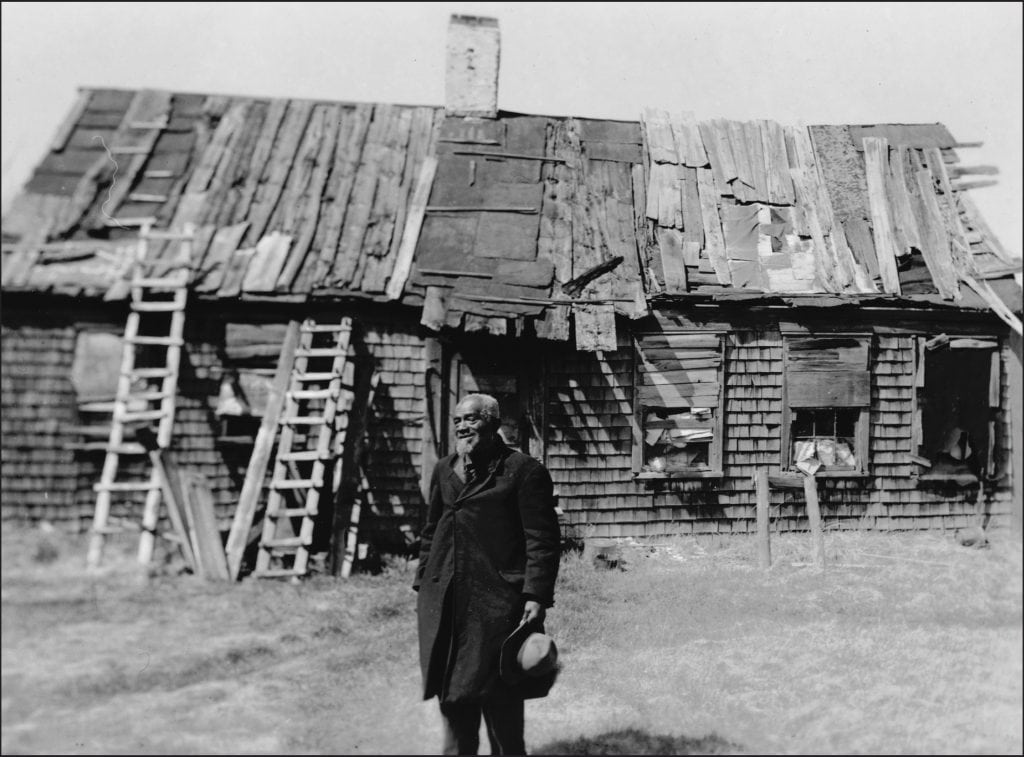

Here is Henry Robinson, one of the former slaves interviewed in the 1930s as part of the federal government’s slave narratives project. Unfortunately, it appears there were no photographs associated with the Fisk University slave interview project that was done about a decade before this photo was taken. (Library of Congress photo)