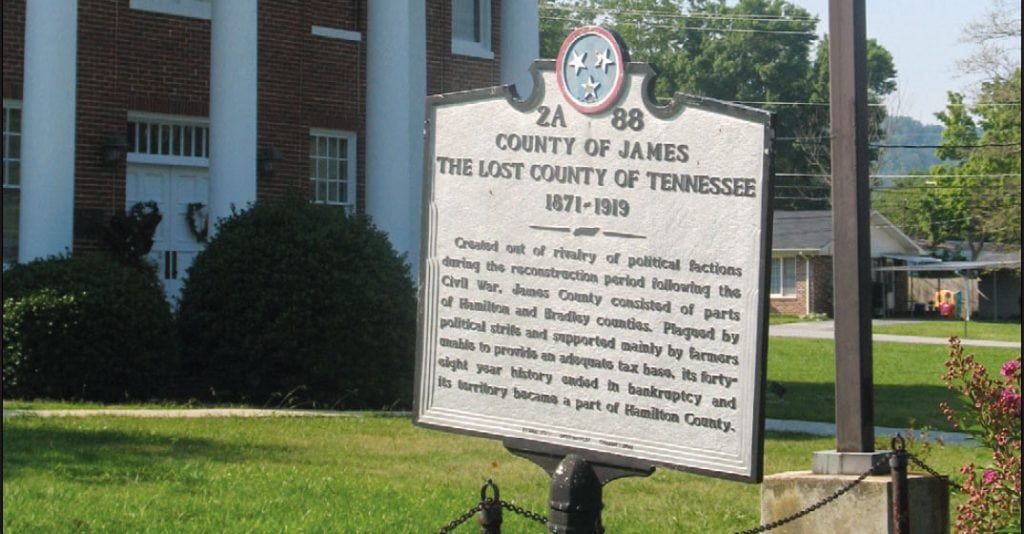

James County was removed after World War I. Why?

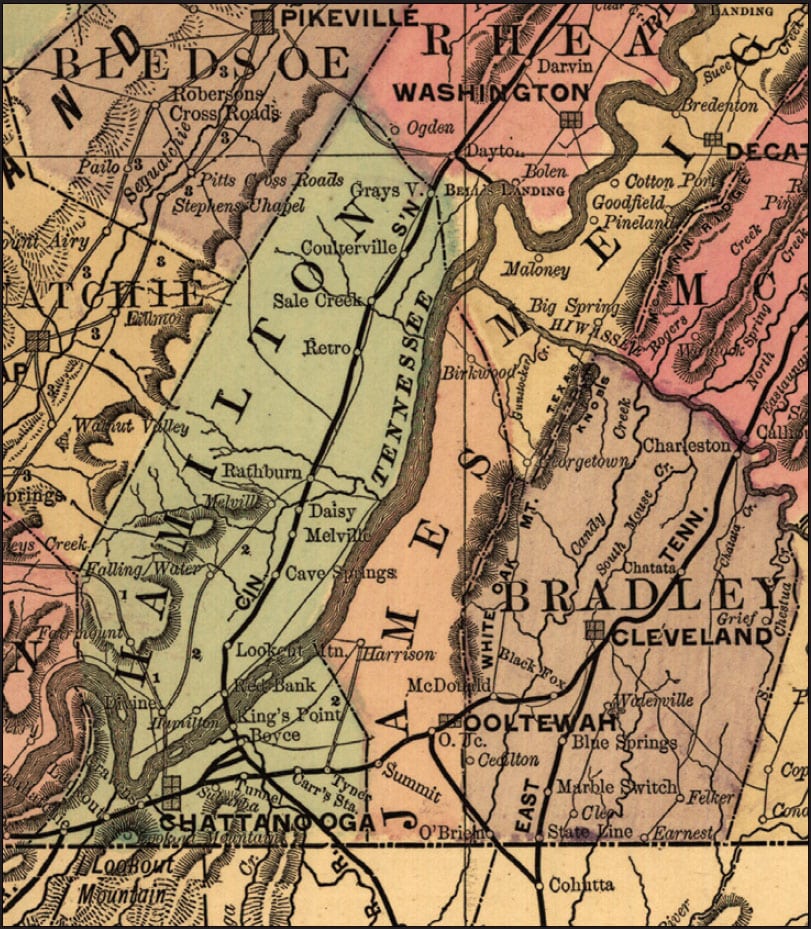

Tennessee has 95 counties. Few people are aware that there used to be a 96th. Known as James County, it was a small sliver of a county east of Hamilton and west of Bradley. Formed after the Civil War, it was done away with after World War I and is today known as the “Lost County of Tennessee.”

I’ve wondered for some time about why it was created and then abolished. A few months ago, Mike Carter, who represents parts of Hamilton County in the Tennessee State House, made me aware of a 1983 book about James County’s history.

Although the book leaves many questions unanswered, it did tell me quite a bit about the story of James County, information I’ve been able to supplement through old newspaper articles

Chattanooga was not the original seat of Hamilton County. Its original courthouse was in Dallas, on the west side of the Tennessee River and close to the middle of the county. According to Matthew Rhea’s 1832 map of Tennessee, Dallas was at that time the only town in the state that was along the Tennessee River and south of Rhea County. In fact, there was a Dallas, Tennessee, long before there was a Dallas, Texas.

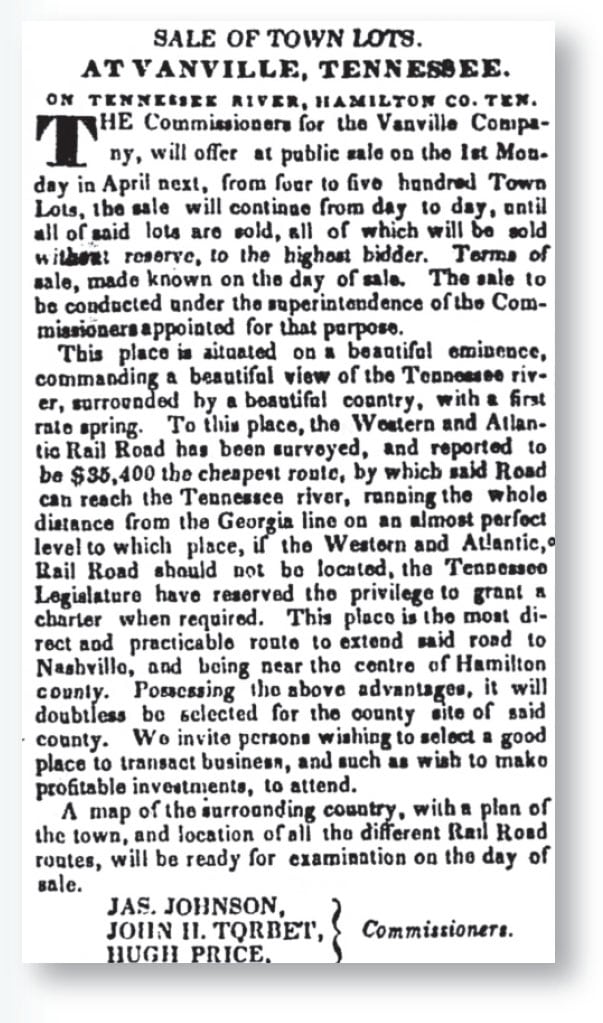

In 1839, after Indian removal, real estate developers created a new town across the river from Dallas on land that had previously been the plantation of Cherokee chief

Joseph Vann. Known as Vannville (and sometimes spelled Vanville), advertisements boasting about its prospects used the word “beautiful” quite a bit. “This place is situated on a beautiful eminence, commanding a beautiful view of the Tennessee river, surrounded by beautiful country,” said the ads. Promoters predicted that Hamilton County would move its county seat to Vanville. They also said that Vanville would become the terminus of two important railroads being discussed at the time — one coming up from Georgia, the other down from Nashville.

Things went well at first. As people began moving into the new community, the town was renamed for William Henry Harrison, who was elected president that year. Sure enough, Hamilton County moved its county seat from Dallas to Harrison. However, the Western and Atlantic Railroad chose Chattanooga rather than Harrison as the destination for its line, as did the Nashville and Chattanooga Railway shortly thereafter.

In the 1840s and 1850s, the riverside community of Harrison had a courthouse, jail, ferry, boat docks, two hotels, three churches, an academy and a newspaper — but no railroad. Chattanooga, meanwhile, not only had Tennessee River commerce but also rail connections to Atlanta, Nashville, Charleston and Memphis. Chattanooga grew much faster than Harrison and rose more in stature when tens of thousands of U.S. and Confederate Army soldiers fought over it during the Civil War. By 1870, Chattanooga’s population far exceeded that of Harrison, and the voters of Hamilton County moved the seat to Chattanooga.

County seats have been moved many times in Tennessee history. But the voters of northern and eastern Hamilton County were especially bitter about the Hamilton County courthouse being moved to Chattanooga. In their defense, the geography of Hamilton County is varied and challenging. In terms of natural barriers, Hamilton County has the Tennessee River, Chickamauga Creek, Lookout Mountain, Signal Mountain, Missionary Ridge and White Oak Mountain — just to name a few. In the era preceding the automobile, I’m not sure if anyone could have found a place to put the Hamilton County Courthouse that would have pleased dissenters.

The citizens of eastern Hamilton County petitioned the General Assembly, asking that they be allowed to form a county. In January 1871, the State Legislature passed and Gov. Dewitt Senter signed an act that did just that. After the citizens of the area approved the change by a vote of 594 to 17, the county was named James County after Rev. Jesse James, a Methodist minister and civic leader (who was unrelated to the famous outlaw).

However, no sooner was James County formed than another controversy developed. The community of Harrison wasn’t centrally located in the new James County. Only three months after it was formed, residents of the new county voted to place its county seat in Ooltewah, a stop on the Southern Railway southeast of Harrison. This heavily contested election divided James County politically and eventually led to Harrison rejoining Hamilton County (in 1893).

By the beginning of the 20th century, James County was long and skinny — about 30 miles from north to south and only about 5 miles east to west. It had only three incorporated towns — Ooltewah, Apison and Birchwood — and very little in the way of industry and commerce. The county became known as “Little Jim” to residents of southeast Tennessee, and there was frequent talk in the newspapers about it being abolished because of its lack of a tax base.

Here are some other tidbits from the 1983 book “James County: A Lost County of Tennessee” by Polly Donnelly:

- The Tennessee General Assembly passed a bill doing away with James County in 1890. However, some of the residents of James County filed a lawsuit charging that this act was unconstitutional, and in October 1890, the Tennessee Supreme Court ruled on their side. James County remained in existence, but the events led many people to assume that the county’s days were numbered.

- James County had notoriously bad roads. In 1887, it took one merchant seven hours to get from Ooltewah to Birchwood by horse and buggy. Through the passage of moderate bond issues, James County tried to improve the roads, but those measures didn’t help much. “There was not a mile of what could be called a good hard-surfaced road,” said Chester Doub, an educator who worked in James County in the early 1900s. “In the wet season, the going was certainly rough, some roads being practically impassable.”

- In 1919, James County had 22 public schools, each very small. The county could only afford to operate these schools as few as four or five months out of the year.

- The James County Courthouse burned twice: in 1890 and 1913. These fires not only burdened the residents with the cost of building new courthouses, but they destroyed most of the records that existed.

Politics probably extended the life of James County longer than it should have. Hamilton County, at the time, leaned Democratic, while James County trended Republican. It wasn’t until after World War I that politicians felt comfortable moving ahead with a new measure to abolish the county. In December 1919, residents of James County voted 953 to 78 to abolish their county and be annexed into Hamilton County. “Taps Sound for James County,” read the headline in the Chattanooga News on Dec. 16, 1919. Shortly thereafter, James County’s records and bond debt were transferred to the Hamilton County Courthouse.

Today, the old courthouse in Ooltewah is used as a wedding chapel.

Finally, this footnote about Harrison: As many of us learned in high school, William Henry Harrison was an inauspicious president, serving 31 days before he died of pneumonia. Perhaps the curse of President Harrison extended to the town named for him. From the time it became the Hamilton County seat, Harrison had no luck. First, it lost to Chattanooga in its bid to get the railroads. Then, after the Civil War, it lost its status as the seat of Hamilton County, again to Chattanooga. Only a few years later, it lost its bid to be the county seat of James County, this time to Ooltewah.

In 1940, the Tennessee Valley Authority completed Chickamauga Dam, flooding most of Harrison for good. In times of low water, one can still see parts of building foundations and roads in and around Harrison Bay, which is named for this notoriously unfortunate town.