Some places are recognized for the important and interesting events that occurred there. Then there is Nickajack Cave in Marion County near the Tennessee-Georgia border. Flooded by the Tennessee Valley Authority and largely overlooked by the historical community, it may be the most forgotten historical site in the state.

Like just about every other cave, there are local legends about murders, moonshining and buried treasure in Nickajack. But the cave and the area immediately around it have also made national history several times.

The Chickamaugans

Today, every fourth-grader in Tennessee is required to learn that a warlike branch of the Cherokee nation called the Chickamaugans emerged in the late 18th century. Under the leadership of Dragging Canoe, the Chickamaugans settled in the mountainous area where the Tennessee River crosses the Cumberland Plateau. There the Tennessee River descended through terrifying navigational obstacles with names such as the Suck and the Boiling Pot. We can only imagine what these legendary areas must have looked like because they are now beneath the waters of a manmade lake.

Nickajack Cave was just downstream from these navigational obstacles. Nickajack, one of the principal towns of the Chickamaugans, was located between the cave and the river.

Starting in 1775, the Chickamaugans staged attacks on settlers in Middle and East Tennessee as well as those such as the famous Donelson Party migrating westward along the river. In Middle Tennessee alone, more than 400 settlers were killed in these attacks. During and after the American Revolution, these attacks were encouraged by both the British and the Spanish — both of which were supplying arms to the Chickamaugans.

In September 1794, an army of about 500 men from Middle and East Tennessee and Kentucky attacked Nickajack. The Chickamaugans believed their village was hidden and could never be found. They were completely surprised by the assault.

Many of the soldiers who attacked Nickajack had friends and family members who had been killed by the Chickamaugans. One of the scouts on the expedition was Joseph Brown, who, as a boy, had seen his father and several of his brothers murdered by Chickamaugans. The soldiers were out for revenge, and they showed little mercy. Soldier James Collier remembered it this way:

“We dashed through the cornfields to the upper end of the town. The Indians had deserted their cabins and fled to the river. Several Indians were killed in the river. One was laying on his face in a floating canoe, reaching his hands over each side and paddling. Several shot at him — I fired two or three times — and at length Colonel Whitley came up and said, ‘Let me have a crack at him.’ I saw the blood spurt out of the Indian’s shoulder, and he made no more efforts.

“At the lower end of the town, where Montgomery’s party was, the water was red with blood.”

Books I have read books claim that as many as 200 warriors were killed that day, but one first-person account tells us the number was more like 50. Nevertheless, it was enough to force the Chickamaugans to agree to peace.

Even if nothing else ever happened at Nickajack, the 1794 military engagement should be enough for the place to be revered. In 1955, a journalist named Zella Armstrong wrote that Nickajack and the area around it should be a state historical park because “it was not until their destruction that Tennessee could be peaceably settled.”

Tourist attraction and saltpeter mine

I sometimes wonder about what the land in front of Nickajack Cave must have looked like after Indian removal in 1838. It is amazing to contemplate the idea that there were remnants of an active Chickamaugan village at Nickajack. But today we know nothing about what it actually consisted of or where the buildings were.

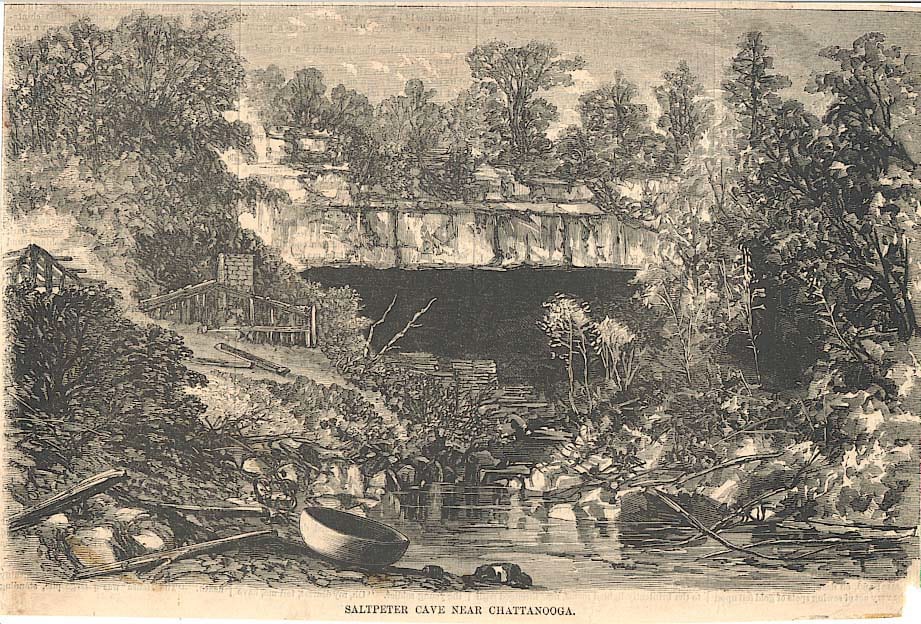

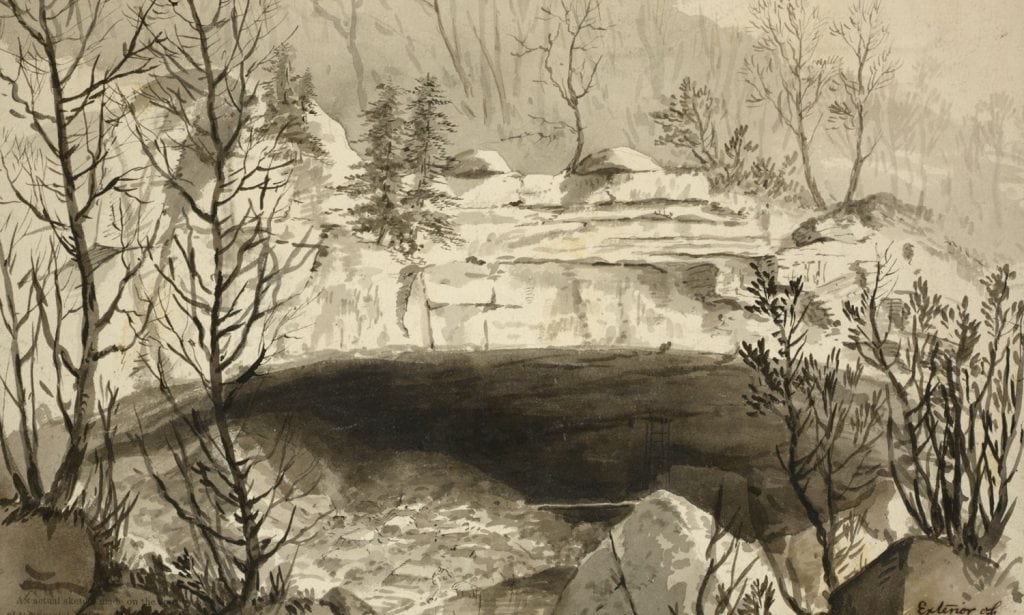

We do know that a lot of people visited Nickajack Cave. I found an article in Harper’s Magazine indicating that as early as the 1850s, people would ride boats down the treacherous stretch of the Tennessee River from Chattanooga to Nickajack as a form of amusement, then explore the cave. Later, during the Civil War, Nickajack Cave “was visited by more soldiers than any other cave” in the United States, according to a 1974 article in The Journal of Spelean History.

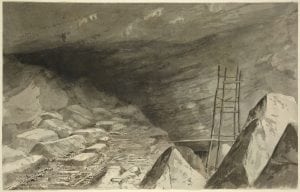

One of the Union soldiers who visited the cave during the war said it was about 15 miles long and had a large stream running through it. “Some distance, after crossing the river, you come to a small chamber, which is very pretty,” David Lathrop from Illinois wrote. “The ceiling is ornamented with stalactites, resembling icicles, and the walls are perpendicular and smooth. The corners and edges of the ceiling are as though they had been ornamented by some master workman.”

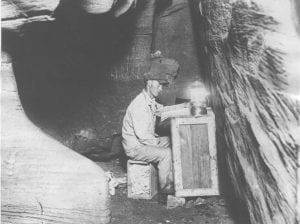

Both Confederate and Union armies used the cave as a saltpeter mine during the Civil War. (Saltpeter, also known as potassium nitrate, was used to make gunpowder.) As many as 100 men worked in Nickajack Cave at one time, books about the war tell us. Its loss after the battles of Chattanooga was a major blow to the Confederacy.

Johnny Cash

At least twice in the early 20th century, promoters bought Nickajack Cave in an attempt to make money operating it as a tourist attraction. The first was Lawrence Ashley, who brought national publicity to the cave when he got lost inside it in 1927. The second was Leo Lambert, who also owned Ruby Falls near Chattanooga.

People were drawn to visit the cave because of its lovely and unique features such as a gigantic stalagmite called “Mr. Big.” They were assured that the cave had the longest underground lake in the world (a claim that probably wasn’t true). They were told it was the only cave in America that wound its way under three states (a claim that probably was true).

In the mid-1960s, TVA announced it would permanently flood Nickajack Cave with the construction of Nickajack Dam just downstream from it. There were many published articles about the cave and its history, one of which drew the attention of a troubled country music star named Johnny Cash.

You can read more about Cash’s visit in his autobiography or in the book “Johnny Cash Walked the Line” by Christopher Stratton. To summarize: In the fall of 1967, Cash walked into the cave intending to kill himself but walked out of the cave a changed man. “He lay in the darkness for hours feeling sorry for himself — for the lives he had ruined and the body he’d abused,” Stratton wrote. “But down in those unfathomable depths, everything changed. His mind became clear, and he started focusing on God.”

For the rest of his life, Cash maintained that he was born again in Nickajack Cave.

The foolish diver

On Dec. 15, 1967, TVA closed the gates of the new dam, permanently flooding Nickajack Cave and the land in front of it. There was some talk about building a levee to protect the cave, but TVA didn’t do that sort of thing very often, especially for an unpopulated area. There was also talk of an extensive archaeological dig in front of the cave, but I’m sad to report that it was not done.

A few years after Nickajack was flooded, TVA made the cave off limits to protect the gray bats that live inside it. “No Trespassing” signs were posted in the front of the cave, and fences were installed to keep people out. But in August 1992, two divers ignored the warnings and entered the cave. They intended to explore it underwater, believing that they could reach large, unflooded parts of the cave deep inside. However, one of them, David Gant, eventually surfaced in a small air pocket deep in the cave without enough oxygen in his tank to get out.

Gant spent 14 hours alone deep in Nickajack Cave, convinced he was going to die. He would have died, in fact, had TVA not lowered the level of the lake to assist in his rescue. So certain was he of his pending death that Gant reportedly asked his two rescuers if they were angels. “We’ve been called a lot of things,” one of them said, “but not angels.”

At Nickajack, the Chickamaugans were annihilated, Union and Confederate soldiers mined saltpeter, generations came to vacation and Johnny Cash became a Christian. However, few people venture down Tennessee Route 156 to see the flooded mouth of the cave. You can go see it if you like, and you can venture close to the entrance by walking a short trail at the Nickajack Cave Wildlife Refuge. If you do visit the site, I hope you find less litter there than I did. I also hope state and local officials can do more to tell the story of the cave to people who visit.

Thanks to cave historian Jim Whidby, “Chronicles of the Cumberland Settlements” editor Paul Clements and “Caves of Chattanooga” author Larry E. Matthews.