In 1846, a bookseller was arrested in Columbia, Tennessee, and accused of circulating abolitionist literature — a crime as illegal then as selling crack cocaine is today. The man, Alanson Billings, was tried and found not guilty. But his story should remind us that slavery and free speech were not compatible.

I first discovered this case when I researched my 2018 book “Runaways, Coffles and Fancy Girls: A History of Slavery in Tennessee.” Recently I dug up more details thanks to the folks at the Maury County Archives.

Here’s the gist of the story:

Alanson Billings was born in New York in 1795 and served in the War of 1812. In the 1830s, he became a bookseller in Buffalo, New York, and then in Louisville, Kentucky.

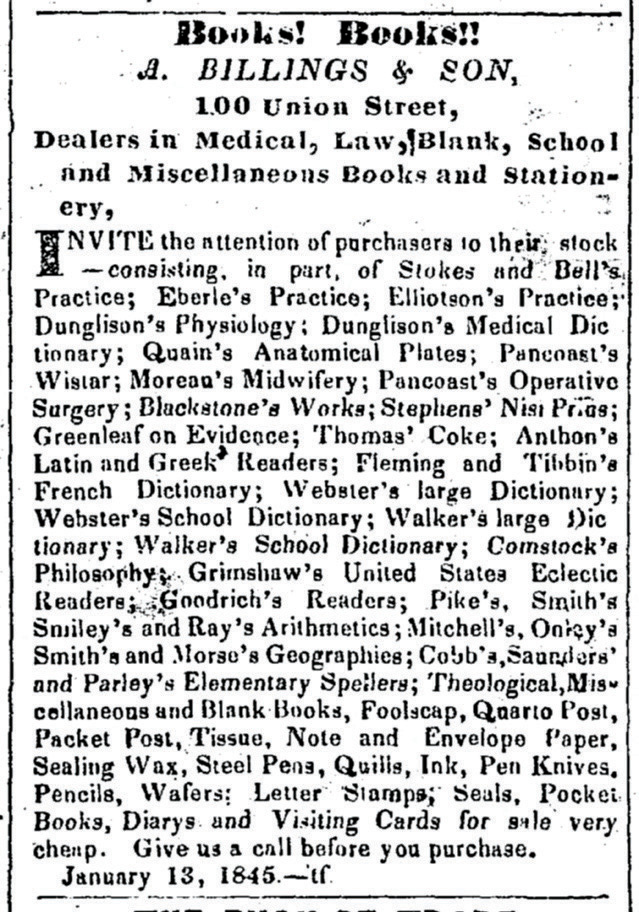

In 1839, Billings opened a store at 100 Union St. in Nashville. For the next seven years, his store ran advertisements in Nashville newspapers. He sold Bibles, medical journals, dictionaries, military manuals, history books, novels, drawings, quills, ink — everything an educated person would want.

Every so often, Billings went on selling trips to places like Columbia, Fayetteville and Shelbyville. In January 1846, on one of these selling trips, he was arrested in Maury County. A few days later, he wrote this account of what happened:

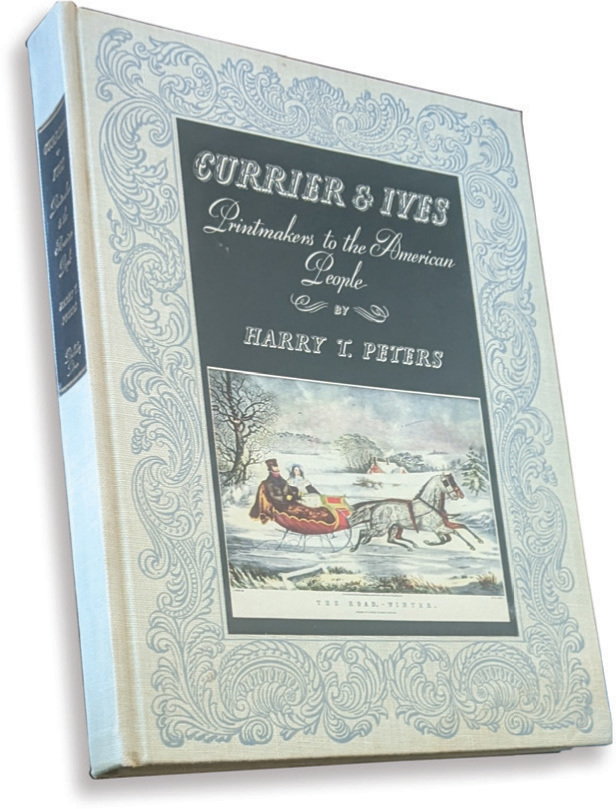

“I opened my stock of books in a store which I had rented. Amongst my lithographic prints was one representing ‘Branding slaves on the coast of Africa previous to their Embarkation’ (a print produced by the New York firm of Currier’s). … A young man came in and said it was an abolition document. I remarked that if I thought so, I would not have it about me, nor say anything that appeared like abolitionism. I heard no more of the picture until Saturday — which was two or three days after the above conversation — when another person walked behind my counter and picked out the aforementioned print, saying this was the one I want … in an hour afterwards the Sheriff came to me with a warrant.”

Billings spent two nights in jail before some friends bailed him out. When he got back to Nashville, he sent the above account of his experiences to the (Nashville) Republican Banner and added:

“As to my being an abolitionist, I deny the charge wholly, publicly and privately, and for those who accuse me of being an abolitionist, I care not.”

You might ask why Billings had to deny being an abolitionist. In fact — First Amendment notwithstanding — it was against Tennessee law to sell or distribute any literature that criticized the institution of slavery.

The most famous bookseller found guilty of violating this law was Amos Dresser of Ohio. In 1835, Dresser was accused of attempting to sell abolitionist literature in Nashville. He was whipped on the Public Square — an event that horrified newspapers in the North but which the Republican Banner thought lenient. “Had it not been for the prudence and firmness of the committee, his life would have been the immediate forfeit of his crime,” the paper said. “As it was, he escaped with the infliction of twenty stripes upon his bare back.”

Less than a year after Dresser was beaten, the Tennessee General Assembly made Tennessee’s anti-abolitionist law harsher. “If any person shall knowingly circulate or shall aid and abet in circulating in this State any paper, essay, verses, pamphlet, book, paintings, drawing or engraving … calculated to excite discontent, insurrection or rebellion amongst the slaves or free persons of color,” the new law said, “such person shall be deemed guilty of felony, and for the first offense, on conviction thereof, shall suffer confinement at hard labor in the public jail or penitentiary house of the state for a period of not less than five nor more than ten years.”

Back to Alanson Billings:

Through the spring of 1846, Billings continued to operate his Nashville shop. Then, in June, he announced his bookstore would close. “Being desirous to change my business, I now offer my entire stock at the lowest possible prices,” he said. Today, we don’t know what role the fear that he might be sentenced to hard labor played in that business decision.

The case came up on the Maury County circuit court in early September. After considering the evidence, the jury could not agree on whether to convict or acquit Billings. Finally, Attorney General Nathaniel Baxter entered a motion of “nolle prosequi” — which meant the state dropped charges. But in a strange footnote, Billings was ordered to pay the cost of his jail time and of his prosecution — including $1.75 for the cost of his lodgings.

Billings reopened his bookstore in 1847, but the next year he was the statewide salesman for a cough medicine. Sometime in the 1850s, all mention of his name vanished from the public eye. When he died in 1864, it didn’t make the newspaper.

During the years following the Civil War, there developed in the South a belief that society before the war was nobler and more genteel than society after the war. People forgot about the effect slavery had — not only on the former enslaved but also on everyone else.

On June 30, 1905, the Nashville American published an article about a walking stick owned by James S. Billings, who ran a cigar stand at the Tulane Hotel. The article said the stick had originally belonged to James’ grandfather Alanson. “Alanson Billings was an old stationer of the earlier days … and he sent his wagon through the country loaded with books, a practice that has long ago ceased,” the article said.

Another bookseller found guilty of violating this law was Amos Dresser, who was accused of selling abolitionist literature in Nashville in 1835 and was whipped on the Public Square. The Nashville Republican Banner thought it a lenient punishment: “Had it not been for the prudence and firmness of the committee, his life would have been the immediate forfeit of his crime. As it was, he escaped with the infliction of twenty stripes upon his bare back.”

“That was before the day of the railroad, the telegraph and the telephone — it was in the sweet old time of which we dearly love to hear, when our grandparents went hand in hand to church or school. … Such relics as this stick take us back into a sacred past, around which clings fond memory and places us again on our mother’s lap.”

The American failed to mention that in the “sacred past” of the 1840s, the stick’s original owner was arrested and nearly sentenced to five to 10 years of hard labor simply because he sold a Nathaniel Currier illustration. Like so many turn-of-the-century writers, the columnist ignored — or simply didn’t know — the effect slavery had on, among other things, the act of selling books and drawings.

Finally, an interesting footnote about Alanson Billings. Not only had his story been lost to Tennessee history, but his tombstone was very nearly lost as well. About eight years ago, Donna and Jim Kasper were digging trenches for utility lines in the front yard of their Sumner County residence. The heavy equipment they were using struck something huge, which turned out to a tombstone that had been knocked over and buried for many years. That led to the discovery of other tombstones — one of which turned out to be that of Alanson Billings.

The Kaspers have gone to great lengths to take care of Billings’ grave and others that have been found in the area.

“We love being the caretakers of all the history on our property,” Donna Kasper says.