In the early decades of American history, Tennessee was regarded as the West. But for some people, it wasn’t west enough.

Joseph Walker is a good example of the trailblazers who looked farther West. Born in Roane County in 1798, Walker moved to Missouri with his family when he was about 20. A few years later, he headed to the Rocky Mountains for the first of many times in a career that had a big impact on American history.

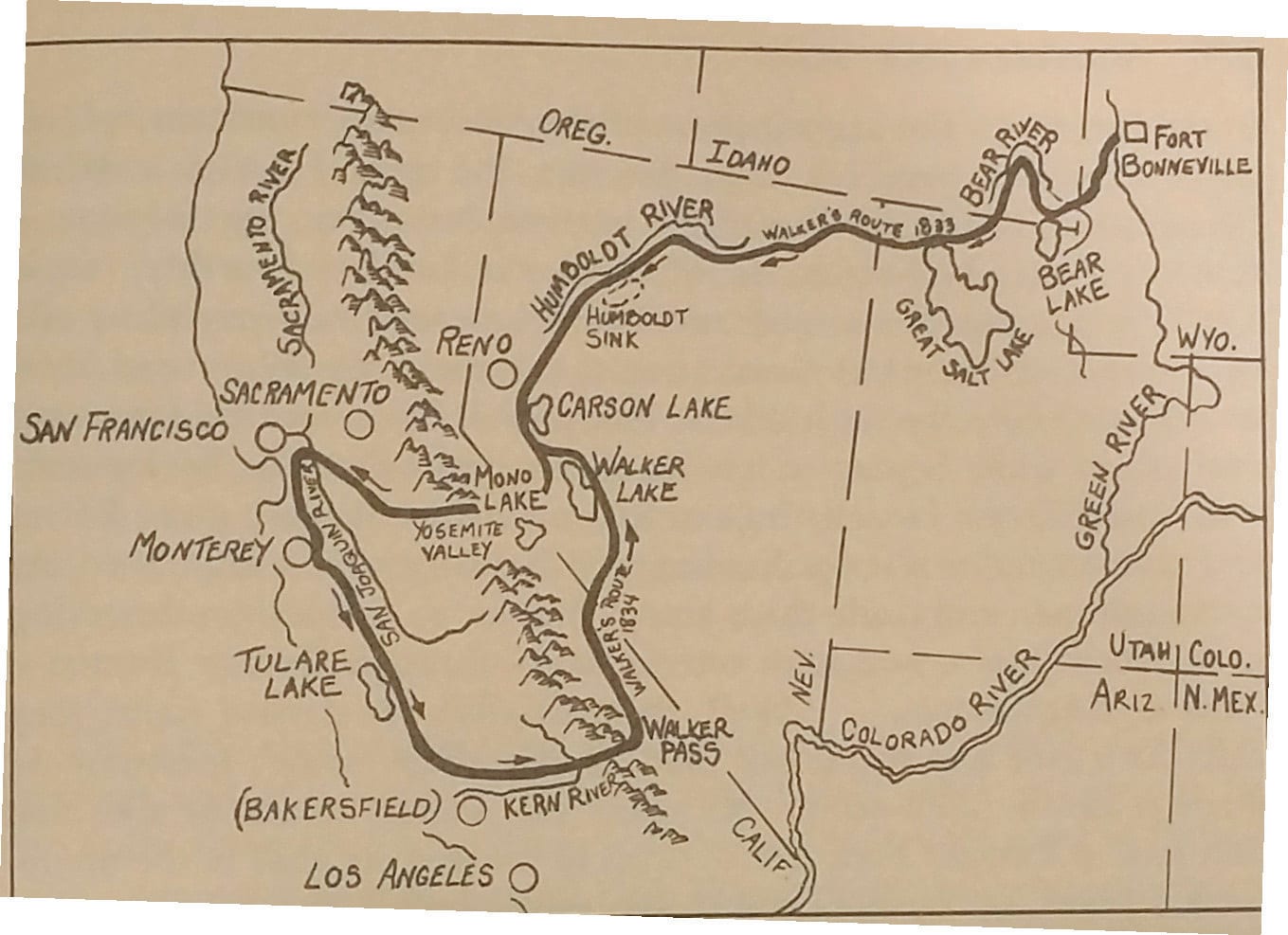

Here is a description of his most epic journey:

In 1832, American Fur Company founder John Jacob Astor sent Benjamin Bonneville to explore and map the West. Bonneville hired Joe Walker — said to have more experience traveling through the far West than just about any other American at the time — to be one of his scouts.

Bonneville’s expedition left in 1832. After passing through South Pass, Wyoming, they spent quite a bit of time building a fort called Fort Bonneville. Then the group split up and continued west. About half (led by Bonneville) headed northwest along the Oregon Trail while the other half (led by Walker) went southwest to find the best way to California.

Walker’s men explored the Great Salt Lake, looking for a river (on maps at the time) that allegedly flowed west from the lake all the way to the Pacific Ocean. It took them weeks to search all the land around the Great Salt Lake. In the process, they discovered that there was no such river and that the old maps were wrong.

Walker’s men then headed into the Great Basin Desert, found the Humboldt River basin and followed it across most of present-day Nevada. They then met up with Paiute Indians. At first, relations between Walker’s men and the Paiutes went well, but then a couple of the explorers killed three of the Indians. A few days later, hundreds Paiutes descended on the expedition, looking like they were about to attack. Walker’s men opened fire. About 40 Paiutes, none of whom had weapons more advanced than bows and arrows, were killed in one of the far West’s first Indian massacres.

In early October 1833, Walker’s men reached the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. They then spent weeks trying to cross them and nearly died in the process. According to Walker’s biographer, “Shortly they were above the snow and often the tree line, trying to cope with snow-filled crevices, icy rock falls and cliffs down which they had to rope themselves and their horses. They struggled ahead on half rations, making many camps where they spent a freezing night without either food or fire, huddled in their blankets and wet buckskins.”

Unable to find food, Walker’s men resorted to eating no fewer than 17 of their horses (many of which were starving themselves).

Somehow, all of them survived. On Oct. 20, the expedition looked down upon the most beautiful thing that any of them had ever seen — Yosemite Valley. “Some of these precipices appeared to us to be more than a mile high,” wrote one of the men. It took nearly a week, but they eventually found an Indian trail that led down into the valley and out of the mountains. The party began to find live game again such as deer and bear, and the journey got a lot easier.

A map from “The Westerling Man” by Bil Gilbert shows the route Joseph Walker took from Fort Bonneville to the Pacific Coast.

However, many adventures were yet to come. They found massive redwood trees 18 feet in diameter, much larger than anything in the East. They witnessed a meteor shower so intense that people all over America thought the world was coming to an end. Finally, they reached the Pacific Ocean, near San Francisco Bay. As they looked out onto the open sea, they saw something that at first made them think they were hallucinating: a sailing ship on the horizon. They managed to wave it to shore, and it turned out to be a whaler from Boston called the Lagoda.

After a few days resting and celebrating with the Lagoda’s crew, Walker’s party proceeded south to Monterey, where Walker met with Jose Figueroa, the Spanish governor of California. Figueroa told Walker that he and his men were welcome to stay, which they did for that entire winter of 1833-34. After what they had been through, the winter with the Spanish and the California Indians was idyllic.

In February 1834, Walker and 52 of his men began their journey back from Monterey. Since they had no desire to go the way they had come, they headed south, looking for a pass through the mountains. After a few days, they met a friendly tribe of Indians known as the Tubatulebal in the San Joaquin Valley. These Native Americans showed them a way through the mountains — a pass about a mile above sea level.

Now east of the Sierra Nevadas, Walker’s men still weren’t out of danger. During the next weeks, they crossed areas (Death Valley, for instance) that were so barren and hot that they had to drink the blood of some of the cattle they had brought from Monterey. Eventually, however, Walker made it to the planned rendezvous with Bonneville’s party.

This remarkable journey was but a chapter in the life of Joe Walker, mountain man and trailblazer. He guided wagon trains from Missouri to California. He was a scout for John Fremont’s second expedition. He led an expedition that discovered gold near present-day Prescott, Arizona.

I believe, however, that Walker’s 1833-34 journey through Utah, Nevada and California is the one that contributed the most to American history. The expedition discovered what is now Yosemite National Park. It also found the pass in the Sierra Nevada Mountains that tens of thousands of migrants used when they came west on the California Trail. Called Walker Pass, it is named for a mountain man born in Roane County, Tennessee.