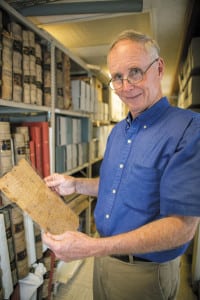

Paul Clements spent 11 years researching first-person accounts of the early settlements of Middle Tennessee. He assembled every available account of events such as the journey of the Donelson Party, the Battle of the Bluffs, the Nickajack Expedition and countless other events between 1775 and 1800. He recently published many of these in the book “Chronicles of the Cumberland Settlements.” This amazing 800-page volume sheds new light on the early history of Nashville and proves that many of the stories we have heard only tell part of the story. Here are Clements’ edited responses to some of my questions:

Where did you find all these first-person accounts?

They came from all over the place. But some of the most important information came from Lyman Draper and Edward Swanson.

Draper was a historian from up North who was fascinated by the story of the American frontier. In the 1840s he interviewed people who had been some of Middle Tennessee’s earliest settlers. He recorded his interviews in notebooks, with the intention of writing a great book about the American frontier, but he never wrote it. There was a lot of microfilm to go through, and because Draper’s handwriting is even worse than mine, it took a good bit of effort to translate what he had written.

And a great deal of crucial information was found about 30 years ago in a house in West Tennessee. The information came from Swanson, who, early in 1779, when he was around 18 years old, came to French Lick (present-day Nashville) as part of an expedition led by James Robertson. Swanson had a powerful memory and eventually provided a wide range of information, including a detailed description of the fort at French Lick, which has given historians a level of information about that structure that no one would have thought possible.

I also should point out that John Haywood’s book, “The Civil and Political History of Tennessee,” came out in 1823. Haywood made an enormously important contribution to the history of the state, but a great deal of information has come to light since it was written, and it contained some inaccuracies.

Based on your research, what are some of the long-repeated stories about Middle Tennessee history that might not be true after all?

I think the main thing that becomes obvious is that, when you have many accounts of the same thing, the versions of what happened vary a bit. There are about a dozen first-person accounts of the Battle of the Bluffs, for instance. If you read them all, you start to wonder whether Charlotte Robertson actually turned the dogs loose on the Indians who were attacking the fort.

Also, history books tell you that James Robertson and his party arrived at the French Lick and crossed the frozen Cumberland River on Christmas Day 1779. This is a good story, but it almost certainly isn’t accurate. Daniel Smith, who was a very discerning and intelligent man, kept a journal that winter, and he recorded that, some distance to the north, the river did not freeze until nearly two weeks after Christmas. What appears to have happened is that the Robertson Party arrived at Mansker’s Station (near the site of present-day Goodlettsville) sometime before Christmas. They stayed there for a time, and then, sometime in mid-January, they crossed the frozen Cumberland River and built Freeland’s Station, where Werthan Bag later stood.

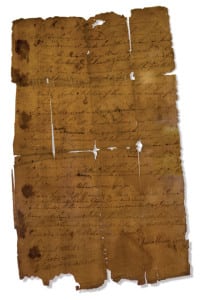

What did you learn about the authenticity of Donelson’s journal?

The Donelson journal is an important document, but Col. John Donelson only wrote the first several entries. The rest of it was written as much as 45 years later by his son, Capt. John Donelson. The initial entries are in the handwriting of the father, but the rest of the journal is in the handwriting of the son. One of the later entries refers to “General” James Robertson, who didn’t become a general until many years later. There are a number of other inconsistencies, but the smoking gun is a written acknowledgement from a son of Capt. John Donelson that the journal was written not by his grandfather, Col. Donelson, but by his father, Capt. Donelson.

It is clear that the elder Donelson kept a journal for the first part of the trip. But after the boats were attacked and the journey became a life-and-death struggle, he stopped making entries.

It was probably more than 40 years later, after Haywood’s history came out, that Col. Donelson’s son, John Donelson Jr., took the old journal and finished it. He did this to set the record straight and promote the memory of his father. He recorded the things that he and his wife remembered.

It is worth pointing out that the younger Donelson and his wife, Mary, were both on the journey, so it is still an excellent first-person account. It’s just that most of it has been attributed to the wrong individual.

What did you learn about the naming of Fort Nashborough?

In a few early records such as the Cumberland Compact and a handful of land records, there are some references to “Nashborough,” but that appears to have merely been the name preferred by Richard Henderson, who was initially the main force behind the settlement. The name never seems to have caught on. A number of the people who lived there were interviewed over the years, but not one of them ever referred to Nashborough in those interviews. They referred to it as “French Lick Station” or “the Bluff.” But what clearly illustrates that it was not called Nashborough is the legislative act that established the town of Nashville. It refers to “a place called the Bluff, adjacent to the French Lick.”

Your book accounts for more than 500 Middle Tennessee settlers killed by Native American attacks between 1780 and 1797. Which Native American tribes were making these attacks?

Most of the killings are usually attributed to a faction of the Cherokees called the Chickamaugas, but a closer examination of the records reveals that the majority of the attacks on the Cumberland settlements came from Creek Indians, with some killings committed by Delawares and Shawnees.

In his account, Swanson said that the Creeks, whose home territory is in what is now central Alabama, were the attackers at the Battle of the Bluff.

If the Creeks were in on these attacks, why didn’t the settlers cross into Alabama and attack them after they destroyed the Chickamaugan villages along the Tennessee River during the Nickajack Expedition?

The short answer is that the Creeks were allies of Spain, and the federal government was doing everything it could to avoid provoking such a powerful European nation. James Robertson was answerable to the secretary of war, and on several occasions he was compelled to restrain the settlers from taking vengeance.

What did you learn about slaves in the early settlement days?

Slaves were here from the very beginning. At times they fought side-by-side with the settlers and suffered in the same ways. James Robertson was accompanied by a slave whose name was not known until the material from Swanson came to light. The slave’s name was Cornelius. He was the first person of African heritage to be killed at what became Nashville. He died in January 1781 during the attack on Freeland’s Station.

The Robertson family also had a female slave named Hagar. She came with the Donelson Party and helped row the boat transporting the family up the Cumberland River. Other slaves such as Abraham Bledsoe in Sumner County played important roles in defending the settlements.

The first will ever executed in Davidson County was for Jonathan Jennings, who survived the journey of the Donelson Party but was killed near French Lick two or three months after he arrived. In his will he left a female slave to his son. Slavery and slaves were very much a part of frontier life from the start.

As I’m reading all these accounts of settlers killed, I am wondering why I’ve never seen any of their tombstones. Where are all these people buried?

As I’m reading all these accounts of settlers killed, I am wondering why I’ve never seen any of their tombstones. Where are all these people buried?

They were buried all over the place. There was a cemetery near the sulphur spring at a bend in French Lick Branch in what is now north Nashville. People who lived on the Bluff were buried on what eventually became the Public Square. They were buried where they lived and died — in settlements spread across much of what became Davidson County.

Which means we’ve just been building and paving over all these graves for the last 200 years?

Yes, that’s what it means.

What is the main message you’ve discovered from this book project?

Nashville and Middle Tennessee have an immensely important history, but we still don’t know our own story. What took place here in the 1780s is as important to the chronology of American history as what took place at New Orleans in 1815 or at Gettysburg in 1863. If this foothold of western expansion hadn’t held out — and it barely survived — it would have been many years before another attempt at resettlement would have been made. It defies logic to think that the Louisiana Purchase could have happened in 1803 or that Andrew Jackson would have surged into national prominence after the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. If the Cumberland settlements had collapsed, American history would have unfolded quite differently.

All of this happened because a small group of settlers led by James Robertson pulled it off. They were able to hold on. We have what might well be the greatest untold story in America, and it’s high time that the city of Nashville began to properly appreciate the heroism of leaders like James Robertson and recognize its importance in the history of this nation.

To learn more about Clements’ book, “Chronicles of the Cumberland Settlements,” and how to purchase a copy, go to www.chroniclesofthecumberland.com.