It may be true that the modern civil rights movement was the most powerful grassroots movement in Tennessee history. It started in the 1950s and, as we were reminded on the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s death, it is closely connected to the history of Memphis.

Another grassroots movement started in the 1950s was also important in the city’s history. Initiated by a group of “little old ladies in tennis shoes,” as they were commonly ridiculed in the press, this movement still impacts the way the government plans

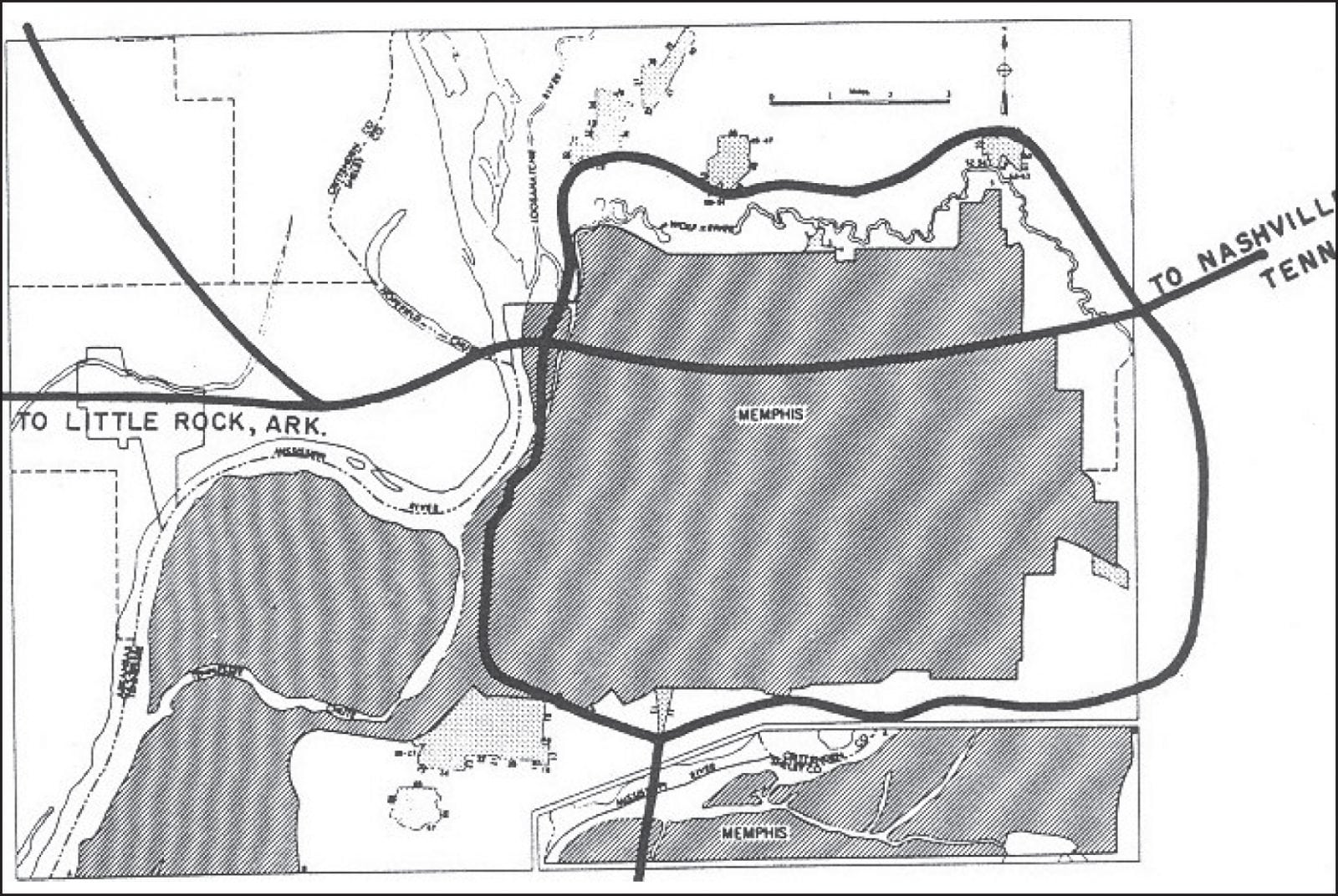

In 1955, the U.S. Department of Commerce released a document that sketched the plan for the interstate highway system. The “yellow book,” as it was known, laid out the general routes of the national interstate system and showed where superhighway corridors would be built in every city that contained them.

In Nashville, Knoxville and Chattanooga, today’s interstate system closely follows the 1955 plan. But Memphis’ system does not.

The yellow book called for I-40 to go directly through Memphis and include an additional 31-mile loop around the city. In the late 1950s, as highway officials began working on the plan, they decided to route six lanes of I-40 through Overton Park, a 342-acre wooded oasis with mature oak trees, a zoo, a nine-hole golf course and other amenities. A group of citizens led by women such as Anona Stoner and Sara Hines opposed the plan and helped form an organization called Citizens to Preserve Overton Park.

At a time when just about everyone — including local and state officials, the chamber of commerce, both Memphis newspapers, the Memphis Parks Commission and most residents — favored the new interstate, the Citizens to Preserve Overton Park appeared to have no chance of success. The only legal weapon the citizens group had was a federal law that said the government could not run any highway through a public park unless there was “no feasible or prudent alternative” to doing so.

Using this clause, Washington, D.C., attorney Jim Vardaman and Memphis attorney Charlie Newman filed a lawsuit claiming (among other things) that there were “feasible and prudent” alternatives to the Overton Park route. The case became known as Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe, and the citizens group lost at the district level and the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

However, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Citizens to Preserve Overton Park in 1971. In an opinion written by Justice Thurgood Marshall, the high court adopted strong definitions of the words “feasible and prudent” and sent the case back to district court to be reheard. The case then dragged on for years in lower court and administrative proceedings.

“A lot of people think that the Supreme Court case settled the matter, but that’s not true,” says Newman, who still practices law with the firm of Burch, Porter & Johnson. “It did, however, give us legal tools that we were able to use in subsequent years.”

For the next decade, the Tennessee Department of Transportation (TDOT) tried to convince succeeding U.S. secretaries of transportation that there was no “feasible and prudent” alternative to the Overton Park route. Newman and his clients argued to the contrary.

Meanwhile, TDOT began building I-40 along the planned route east and west of Overton Park, tearing down hundreds of homes and businesses in the process. This made it seem as though the Overton Park route was inevitable, and it increased pressure on the Citizens to Preserve Overton Park to give up the fight.

“Today, there are people in the environmental community who praise us for what we did,” says Jim Lanier, a retired history professor at Rhodes College who was a member of the citizens group. “But we were not appreciated at the time. A lot of people wanted I-40 built, from suburbanites to the business establishment.”

As the years passed, TDOT even suggested tunneling under the park, a proposal that shot the theoretical cost of the route to as high as $320 million.

However, it wasn’t until January 1981, in the early days of Gov. Lamar Alexander’s administration, that TDOT abandoned plans to run I-40 through Overton Park.

Today, Overton Park thrives, has more visitors than ever and is supported by active nonprofit groups. Meanwhile, the Midtown section of Memphis, which would have been bisected under the I-40 plan, has experienced a remarkable resurgence.

Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe has become a landmark case in administrative law, highway planning and environmental protection. A few years ago, when the federal government routed U.S. Highway 25E in Claiborne County through a tunnel rather than widen it at the Cumberland Gap, the Overton Park case affected the decision-making process.

The Tennessee Department of Transportation has gotten over the I-40 Overton Park controversy and even acknowledges it in official histories. However, I find it amusing that the official TDOT map does not include Overton Park — even in the blow-up sections that show Memphis in detail. If you want to see where Overton Park is, you have to use a Rand McNally or Mapquest map rather than the one given away at statewide rest areas. This is a subtle reminder that a grassroots group led by “little old ladies in tennis shoes” once took on the government of Tennessee — and won.