The story behind historic War Department letter

When you start researching the story behind a single document, you never know where it might lead.

I’ve learned this lesson many times since I began researching Tennessee history, and I just learned it again.

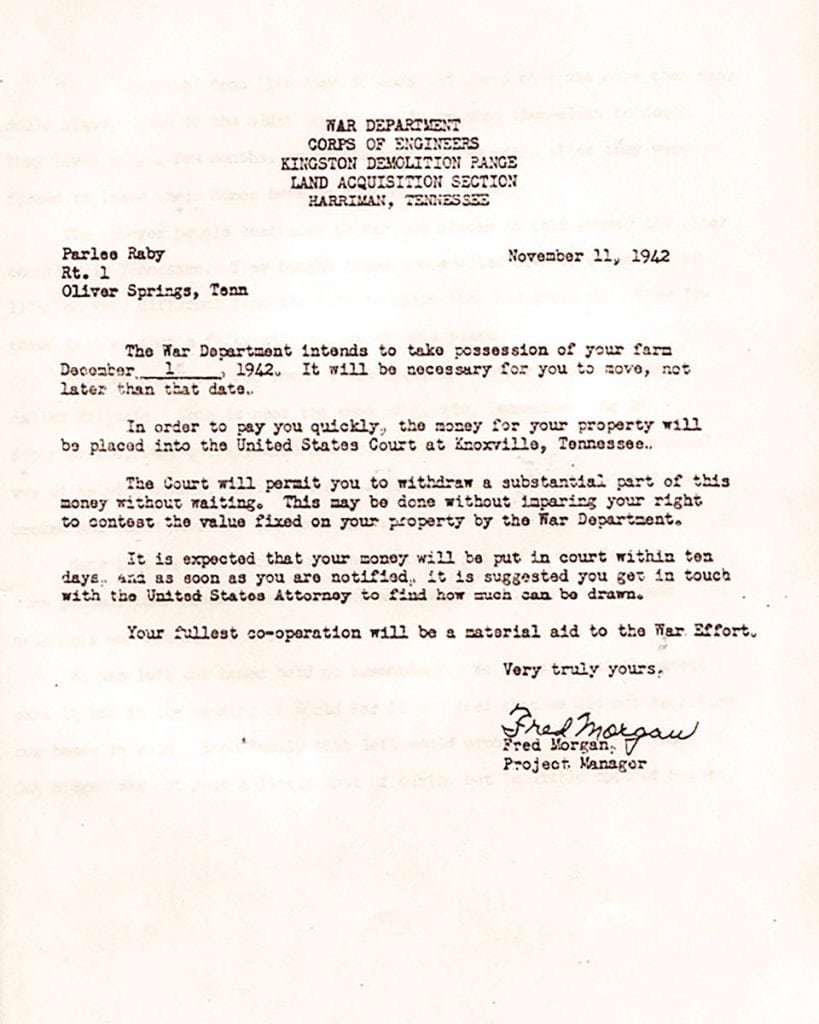

A few years ago, I visited the American Museum of Science and Energy in Oak Ridge. There is a section of it devoted to the process under which the area transformed from remote farmland to part of the Manhattan Project. In that section of the museum is a framed letter similar to the ones property owners in the area would have received in 1942.

“The War Department intends to take possession of your farm December 1, 1942,” begins the letter, which was written only three weeks before then. “It will be necessary for you to move, not later than that date.”

It is a form letter, similar to those that would have been received by everyone else who lived in that part of Anderson County. The first time I read it, I thought about how much times have changed. In 1942 and 1943, the U.S. government acquired about 60,000 acres in and near present-day Oak Ridge. Today, it is amazing to contemplate the government trying to obtain such a large area in such a short period of time. With television and the internet, news about the acquisitions would spread so fast that there is no way the government could possibly keep it a secret (like it did back then). With the emphasis our society now puts on individual rights and litigation, the cases involved in such acquisitions would drag on for years in well-publicized lawsuits.

Imagine how much money the lawyers would make today, I thought.

This particular letter was addressed to someone named Parlee Raby, something I hardly noticed the first time I read it. But after I photographed a copy of it and placed a copy of it on the Oak Ridge virtual tour on my Tennessee History for Kids website, I began to wonder about this.

Who was Parlee Raby, after all? How much land did she own? Was there a story behind her? And since there were about 3,000 property owners forced to relocate, why is this particular letter on the museum wall?

After a few phone calls, a lunch with Oak Ridge historian Ray Smith and a glance through a few history books, I have gotten most of my questions answered. As it turns out, quite a bit has been written in local Oak Ridge history forums about the circumstances surrounding the Raby land.

This isn’t because of the size or nature of the farm itself or what became of the property. Paralee Raby — the government misspelled her first name — owned about 15 acres at the edge of the rural valley (historically known as Bear Creek Valley) in Anderson County. Those 15 acres weren’t the site of any of the major structures used by the U.S. government during the Manhattan Project. It was part of the land north and east of the main factory plants in what became the city of Oak Ridge. After World War II, the land was sold back for private development, and it is now part of a residential subdivision.

The Paralee Raby acquisition is remembered because of its connection to one of Anderson County’s legendary characters. Paralee Raby’s farm, you see, had previously been owned by her stepfather, John Hendrix.

Here the story gets a little complicated. Hendrix was born in 1865, and he and his wife were typical small farmers in Anderson County at the turn of the 20th century. However, as the story goes, Hendrix’s infant daughter died around 1900. His wife blamed him for the child’s death. As a result, she left him, took the rest of the kids with her and moved to Arkansas.

This series of events turned Hendrix into a broken man. He wandered into the woods and spent more than a month living alone, praying for long hours and sleeping on the ground. He probably would have died were it not for a local woman who helped care for him by feeding him chicken soup and bringing a quilt to cover him.

When Hendrix came back from his self-imposed isolation, he told everyone that during his long time alone, he had a vision. According to accounts, Hendrix said something along these lines:

“Bear Creek Valley someday will be filled with great buildings and factories, and they will help toward winning the greatest war that will ever be. Big engines will build big ditches, and thousands of people will be running to and fro. They will be building things, and there will be great noise and confusion, and the earth will shake. I’ve seen it; it’s coming.”

John Hendrix eventually remarried and through his second marriage had a stepdaughter named Paralee Raby. However, he remained a strange man, revered or feared by locals and apt to wander off for long excursions in the woods. Eventually Hendrix fell ill with tuberculosis. Since his stepdaughter agreed to care for him in his old age, Hendrix ultimately deeded his 15-acre farm to her in gratitude.

John Hendrix died on June 2, 1915. At his request, he was buried on top of the hill overlooking the little farm he had given Paralee Raby and her husband, Perry. That area is now Hendrix Creek, a residential subdivision named for him.

After the government came and took their land, Paralee and Perry Raby moved to Hillvale, an unincorporated community near Norris. As the extent of the Manhattan Project became clearer to them, they remembered the strange predictions Hendrix had made years before. Once the United States dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they were amazed. So was everyone else who had known and heard about John Hendrix.

Paralee Raby died in 1949, Perry in 1956. John Hendrix is now known as “The Prophet of Oak Ridge,” and his story is one that is proudly repeated often when visitors come to Oak Ridge.

Ray Smith, official historian for the Oak Ridge Laboratories, credits several people for helping keep alive the story of the Rabys and John Hendrix. One is George Robinson, author of the 1950 book “The Oak Ridge Story.” Another is Ed Westcott, longtime Oak Ridge-area photographer who took a picture of John Hendrix’s grave in 1944.

A third person who shed light on the story was Grace Raby Crawford, the adopted daughter of Perry and Paralee Raby. In a book she wrote called “Back of Oak Ridge” and which Ray Smith published as part of a larger book called “The John Hendrix Story” in 2009, Grace described her mother.

“Paralee’s house was not one of luxury but one of contentment and the love it takes to make a real home,” she wrote. “Paralee was a devoted wife and mother and also ‘loved her neighbor as herself.’ She went into the homes of her neighbors when there was sickness and cared for them, regardless of the type of illness or the weather.”

Ray Smith isn’t certain as to how it was that the Paralee Raby letter made its way to the wall of the American Museum of Science and Energy. But he feels fairly certain that it is because of the Rabys’ connection to John Hendrix, “Prophet of Oak Ridge.”

In any case, that’s the story behind one letter hanging on the wall of one Tennessee museum. There are hundreds of other museums in Tennessee with documents hanging on their walls. I encourage you to find one, put on your detective cap and start digging.