The members of the mob were all hooded and armed. One of them tied a rope around the neck of Quentin Rankin, 39- year-old attorney for the West Tennessee Land Company, and tossed the other end around a strong tree branch. Rankin was lifted into the air for a few seconds. Then he was lowered to the ground.

“Are you gonna compromise?” Rankin was asked. The lawyer adamantly refused.

Rankin was lifted into the air again, then lowered and asked a similar question. Again he said no. “Gentlemen, don’t do that. You’re killing me,” he gasped.

As if that plea were a signal, one of the hooded men fired a shotgun into Rankin’s chest. The noise echoed into the woods and swamps surrounding the lake. It shocked most of the men who were present, many of whom later testified that they had not intended to commit murder that night.

Everyone heard the sound of a man fleeing, then a splash as he dove into the shallow, tree- and stump-filled waters of Reelfoot Lake. Realizing their other prisoner had made a break for it, the members of the mob opened fired in the general direction of the sound. They had no intention of letting Robert Taylor live to see another day.

Reelfoot Lake was formed by the New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811 and 1812. As a result of those upheavals, water overflowed the banks of the Mississippi River and inundated much of present-day Lake and Obion counties. A lot of this water remained, forming a body of water that is about 23 square miles but with an average depth of only about 5 feet deep.

Settlers began moving into northwest Tennessee after the Chickasaw Indians were forced out in the early 1800s. Many of these small farmers found they could help feed themselves and supplement their incomes by fishing in the lake. By around 1900, an estimated 500 families in Obion and Lake counties were doing just that.

However, starting around 1870, a man named James Harris began buying up the land under and around the lake. In 1899, Harris announced that he owned the lake and said he intended to drain it and farm the land under it. A group of business owners and citizens of the Reelfoot Lake area filed a lawsuit aimed at blocking Harris from doing that.

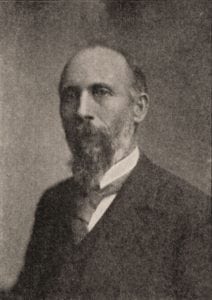

This lawsuit eventually reached the Tennessee Supreme Court and forced Harris to abandon his plans to drain the lake. But after James Harris’ death in 1903, his son (whose first name was Judge) took over the property. In 1905, Judge Harris announced his intention to stop all people from using the lake without paying him a fee. He formed a business known as the West Tennessee Land Company to own, operate and make a profit from the lake and its shoreline.

The people who made their living and fed their families by fishing on Reelfoot Lake felt like they were running out of options. One of them, Tom Johnson of the Obion County community of Hornbeak, later summarized his point of view in this manner:

“[God] saw that we couldn’t make a livin’ farmin’, so he ordered an earthquake, an’ the earthquake left a big hole. Next he filled the hole with watah an’ put fish in it. Then he knew we could make a livin’ between farmin’ and fishin’. But along comes these rich men who don’t have to make no livin’, an’ they tell us all that we must not fish in the lake any mo’, cause they owns the lake an’ the fish God put theah foh us. It jus’ naturally ain’t right, strange; it ain’t no justice.”

At the time, there was a nationally publicized wave of violence in southern Kentucky between tobacco farmers and the American Tobacco Company. As part of that rebellion, many tobacco farmers began attacking tobacco company property and farmers who were siding with the company. These rebel farmers donned black hoods and attacked at night, on horseback, and became known as “night riders.” (There does not appear to have been a direct relationship between the Ku Klux Klan and the night riders.)

Inspired by the night riders in tobacco country, many of the fishermen and their friends — often as many as 100 at a time — began making night rider raids against the West Tennessee Land Company and its allies. The attacks went on for seven months and soon became an instrument of vengeance against people who may or may not have had anything to do with the West Tennessee Land Company.

Paul Vanderwood’s “Night Riders at Reelfoot Lake” is the definitive book on this subject. Researched in the 1950s, Vanderwood interviewed about 25 people from Obion and Lake counties who lived through that era, including seven people who had once been night riders. Here are some of the crimes committed by the night riders, according to Vanderwood’s book:

- They burned the privately owned fishing docks of J.C. Burdick (in Sanburg) to punish him for his business dealings with the West Tennessee Land Company.

- They whipped a physically hunchbacked Lake County official named George Wynne, allegedly for making derogatory comments about night riders.

- They whipped a woman named Emma Johnson because she was attempting to divorce her husband, Joe Walker (a night rider 30 years older than she).

- They crossed into Kentucky and murdered a black man named Dave Walker, along with his wife, daughter and baby — reportedly because Walker had insulted a white woman and pulled a gun on a white man.

It is a reflection of the times that the Walker family murders didn’t compel Tennessee state officials to react (however, the governor of Kentucky did, promising a pardon to anyone who shot and killed a night rider.) Tennessee indignation toward the night riders peaked two weeks later.

On Oct. 19, 1908, West Tennessee Land Company attorneys Rankin and Taylor were dragged from a hotel in the community known as Walnut Log. Rankin was hanged from a tree and shot; Taylor fled into the swamp amid a storm of bullets and was presumed dead by his captors.

However, under a barrage of gunfire, Taylor slipped underwater and hid behind a partially sunken tree that had fallen into the lake. The 63-yearold Confederate veteran remained there in the darkness for nearly an hour until the night riders finally left. Taylor then swam, waded and staggered north and west through swamps and bayous.

On the morning of Oct. 21, Taylor reached a friendly farmer who fed him, gave him medical aid and alerted authorities. By that time, he had been missing for 30 hours and traveled more than 25 miles. The story of his survival was publicized in newspapers across the country. It eventually became Southern legend and was discussed at length in a short story called “In the Miro District,” written in the 1970s by Taylor’s grandson, Peter.

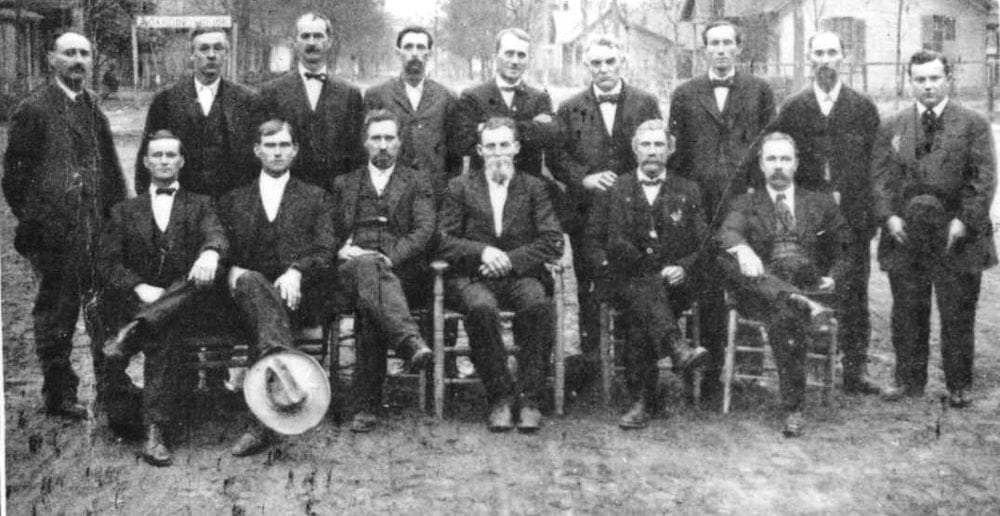

With the murder of Quentin Rankin, Tennessee Gov. Malcolm Patterson finally reacted, calling out the Tennessee National Guard to restore order in the Reelfoot Lake area. Working with law enforcement officials and hundreds of volunteers, they rounded up about 50 suspects.

There was concern that an Obion County jury would never have the courage to convict the accused murderers in the night rider case. However, by that time, many residents of Obion County were more disgusted by the terrorists’ methods of the night riders than they were afraid of them.

In January 1909, a jury found eight night riders guilty and sentenced six of the eight to death. The verdict and the sentence were, at the time, hailed as a triumph of law and order. “The conviction of these men,” said the Memphis Commercial Appeal, “marks the turning point of nightriderism toward its decline.”

However, the Tennessee Supreme Court later overturned these convictions because of the manner in which the judge had chosen the jury. The men were never tried again. There is, however, no evidence that night riders ever committed another crime in the Reelfoot Lake area. “They had experienced a close call with the gallows and had no stomach for further night riding,” one of the officers in the state militia later said.

In 1914, the state of Tennessee purchased Reelfoot Lake and much of its shoreline. A law was passed declaring the lake public domain, which means people can fish there, regardless of who owns the shoreline. Today the lake and much of its shoreline are public property. People fish, hunt and sightsee on and around the lake at places such as Reelfoot Lake Wildlife Refuge and Reelfoot Lake State Park.