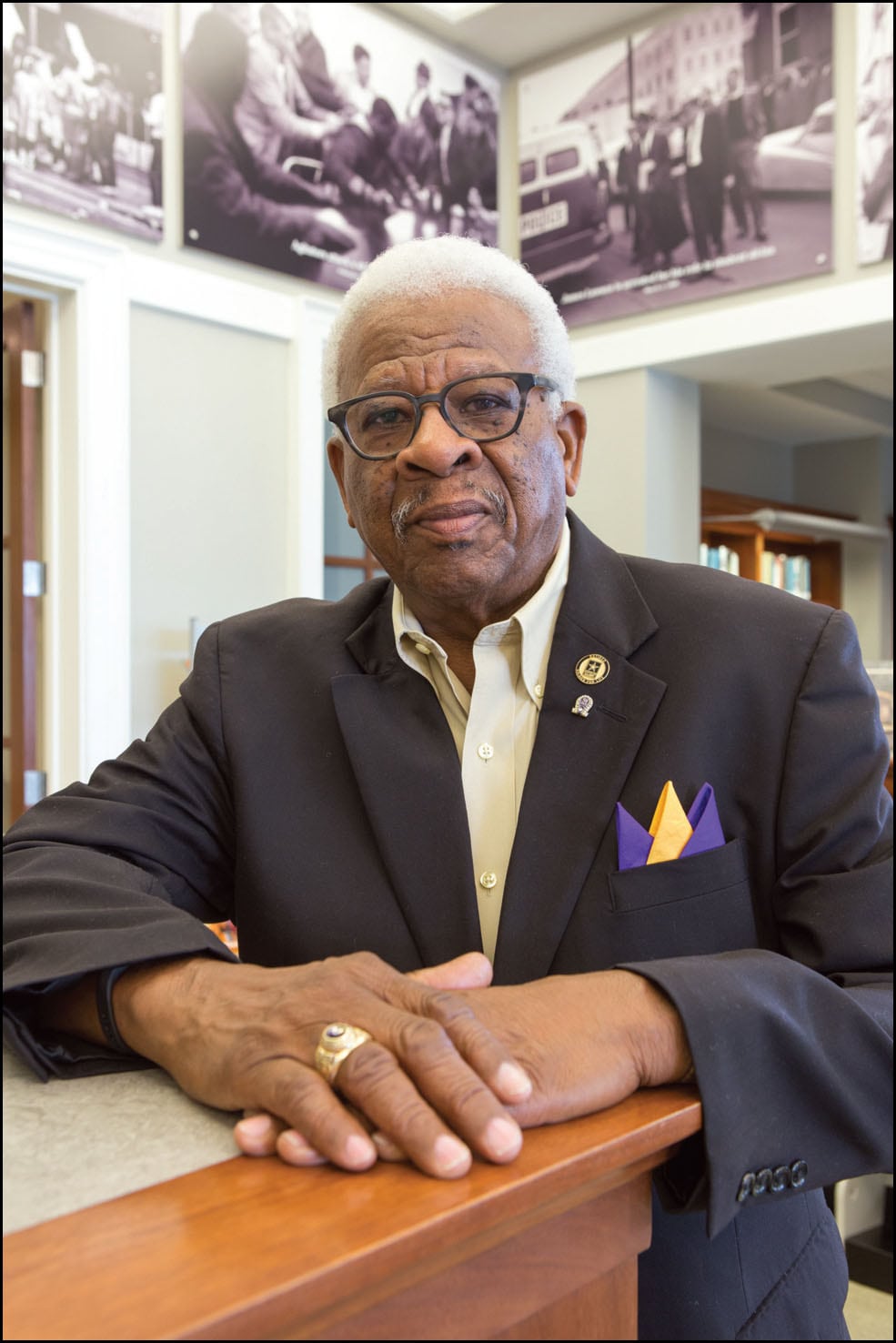

Interview with civil rights icon Bobby Cain reveals fascinating details

I’ve known about Bobby Cain for some time. I’ve known that in the spring of 1957, he became the first African-American graduate of an integrated public high school in the South when he graduated from Clinton High School in East Tennessee. I’ve known that he is a civil rights hero, an overlooked hero, because the integration of Clinton High School in the fall of 1956 received far less publicity than the integration of Arkansas’ Little Rock Central High School a year later.

Yes, I’ve known about Bobby Cain. But I’ve written very little about him because I didn’t know much other than what I just wrote.

This summer, I was privileged to interview Cain on stage at the Tennessee History Tent Revival — an event my organization does every summer to help and inspire educators to teach Tennessee history. I learned a lot more about Bobby Cain.

For instance:

Bobby Cain was not an intentional hero. Bobby and the other members of the “Clinton 12” — as they have recently become known — were not hand-picked and trained like many civil rights icons we know about today. They were just ordinary teenagers from Anderson County who had to transfer from the all-black Austin High School in Knoxville to Clinton High School because of a lawsuit known as McSwain v. Anderson County Board of Education and the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

“I was 16 years old, and I didn’t have any say in the matter,” Cain said.

“We (those who integrated Clinton High School) did not receive any special protections. We didn’t have any support groups, other than the churches we went to.

“The Little Rock 9, on the other hand, were escorted into the school by the 101st Airborne unit. They also received medallions from the president.”

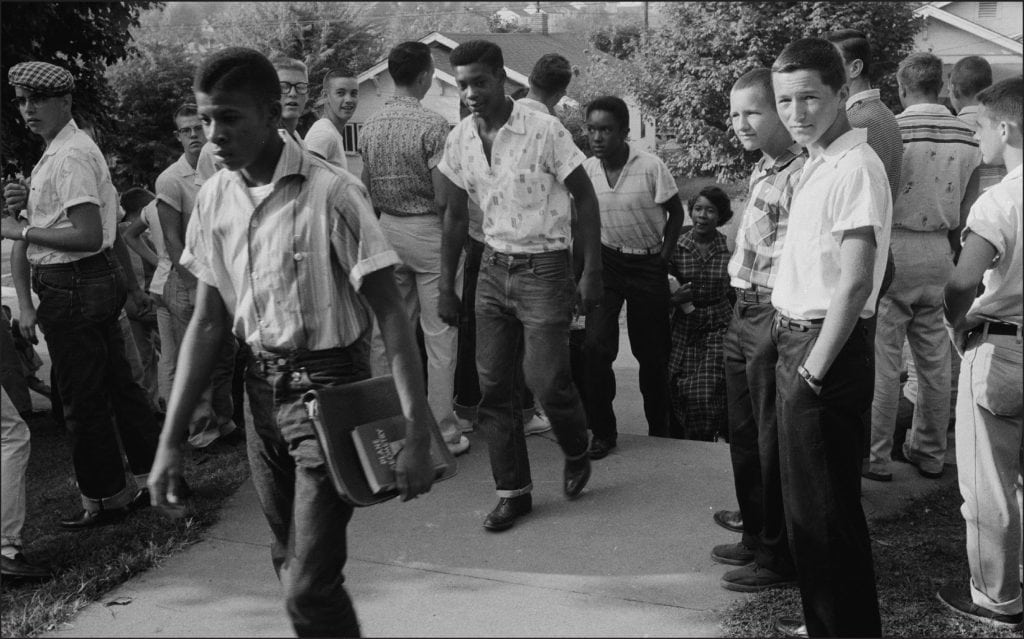

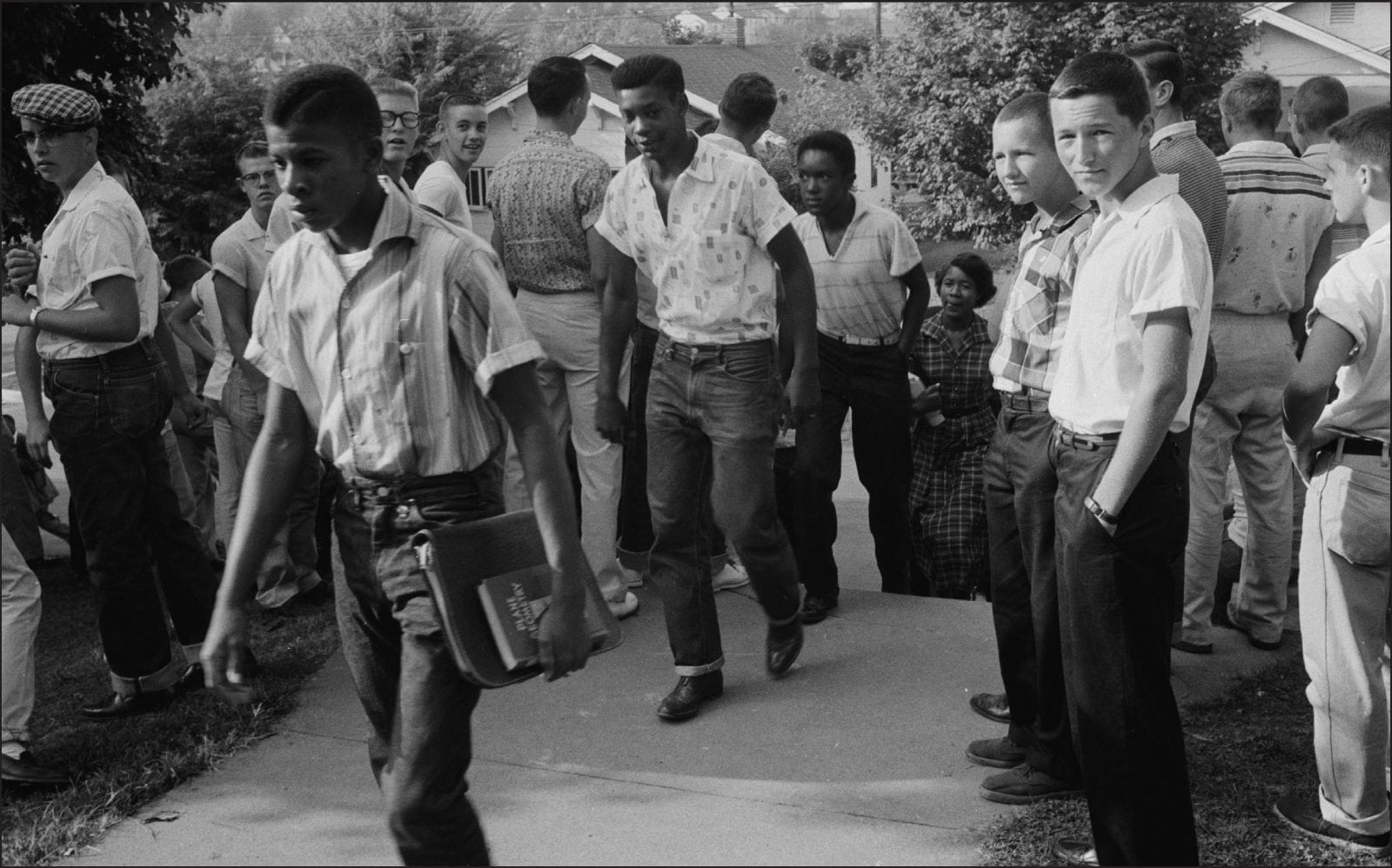

The teachers at Clinton High School were fairly nice to Bobby Cain. However, the white students kept their distance or were hostile, according to Cain. Referring to the iconic photograph of Cain and the other black students walking past all the white students on the first day of school, I asked him how many of the white students he could identify by name. “None of them,” he said. “I pretty much never made friends with any white students.”

“You mean there really weren’t any incidents of white students ‘braving the ice’ and approaching you in the hallway or in class?” I asked.

“Not that I can remember,” he said. “You have to realize that if any white students had gone out of their way to be nice to us, they would have been jumped on.”

There were many times that Cain was pushed or jeered at. “Sometimes I pushed back,” he said. “Sometimes I just walked away.”

The worst part of being a senior at Clinton High School is that almost all of Bobby Cain’s friends were still at Austin High School in Knoxville, where he had previously attended. “I missed my friends, and there really wasn’t any way to keep in touch with them,” he said.

Bobby Cain wanted to play sports, but he really couldn’t. “I was good enough to play,” he said. “I think I was also the fastest kid at the school. “But the coaches at Clinton told me that none of the other high schools would play against us if I was on the field at the game.”

Bobby Cain kept his sense of humor as the year went on. “One time I was heading up Foley Hill when these three white boys pulled up alongside of me in a car,” he said.

“Hey! You know where we can find that Bobby Cain?” one young white man asked.

“Yeah,” Bobby said in response. “He’s down there,” gesturing back toward the school.

Bobby Cain nearly quit. “One day I decided that I couldn’t take it anymore,” he said. “I walked out of the school building and walked home and told my parents that I wasn’t going back.

“They then asked me what I was going to do. They told me they weren’t going to let me enlist in the Army yet, and they told me that they sure weren’t going to spend the money and effort to get me to and from Austin High School every day.

“So they pretty much told me that I had to go back. And I did go back.”

The turning point of the 1956-57 school year, as Cain remembers it, was when a white minister got beaten up. On Dec. 4, Paul Turner, minister of the First Baptist Church, showed his support for integration by walking to school with Cain and the other members of the Clinton 12. After the students got to school, a group of men followed Turner and beat him up.

“It was after that happened that the police began escorting us to school,” Cain remembered.

Turner committed suicide in 1980.

Bobby Cain was one of two black seniors at Clinton High School that year. The other one, Alfred Williams, did not get to go through graduation. “He got in trouble a few weeks before the end of the school year, and they did not let him graduate,” Cain said.

Bobby Cain was not active in the civil rights movement in the 1960s. As best I can tell, he just wanted to get on with his job and his life. But when asked, Cain prefers this quip: “I couldn’t do the civil rights marches,” he said. “You see, you had to agree to be nonviolent (to do that).”

Bobby Cain has lived a relatively normal, quiet life. He hasn’t received the accolades that many other civil rights heroes have received, and he’s not part of the regular speaker circuit.

Cain attended Tennessee State University in Nashville, where he met his future wife, Margo, and graduated in 1961. He worked for the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, served in the U.S. Army and eventually moved to Nashville and went to work for the Tennessee Department of Human Services.

Today, Cain and Margo (a former Metro Nashville Schools principal) are retired. They are active grandparents. Like many North Nashville residents, their house got hit hard by the flood of 2010. Like many North Nashville residents, you might run into them at Swett’s restaurant, public meetings or Tennessee State football games, where they have season tickets.