The name forgotten from when Tennessee became a state 225 years ago

It’s a celebration 225 years in the making. On June 1, events from the capital city of Nashville to Tennessee’s oldest town, Jonesborough, as well as communities across the state will commemorate the day in 1796 when Tennessee became the 16th state.

In keeping with a popular theme of these history columns — highlighting some lesser-known tales of Tennessee’s past — here’s a story from that era you probably haven’t heard:

When it was first formed, half of Tennessee was named for a Spaniard almost no one remembers today.

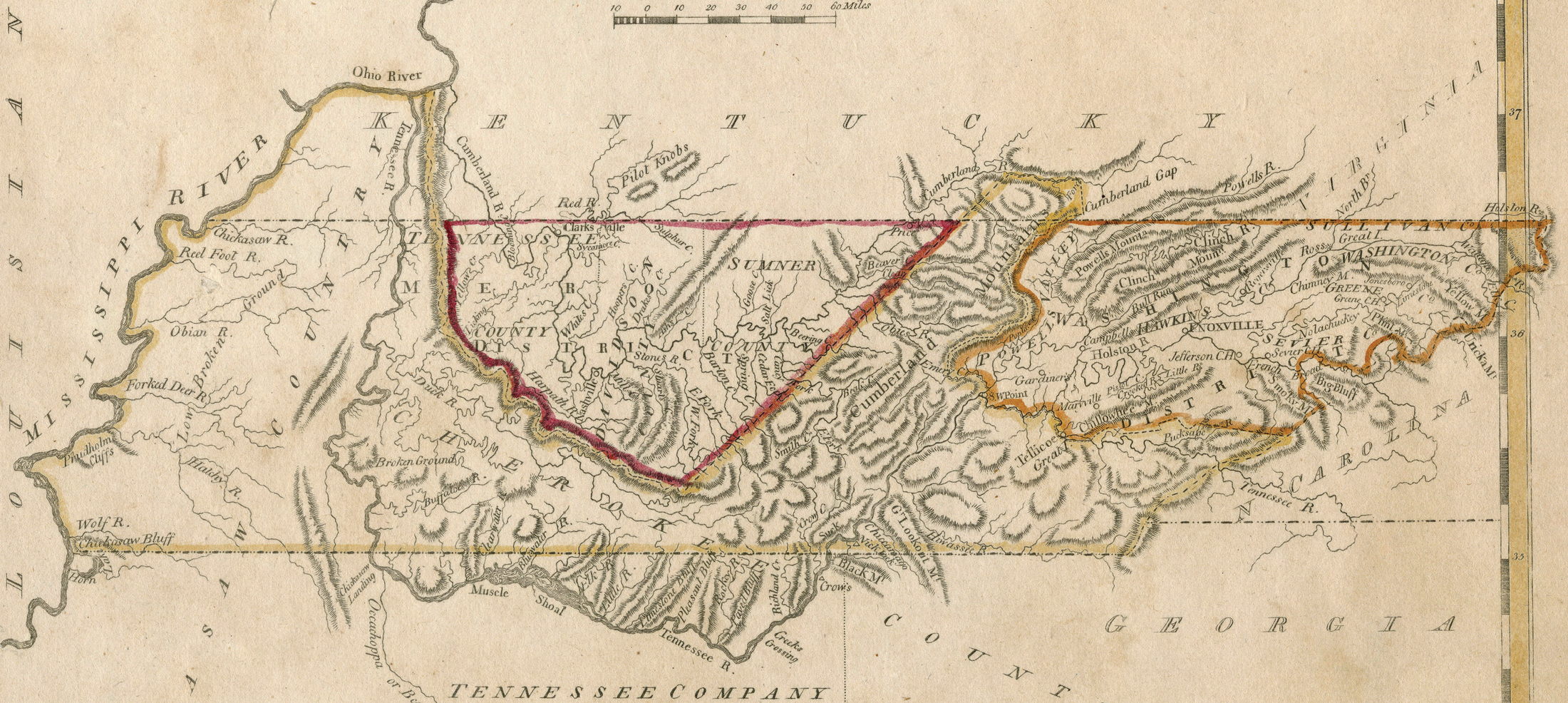

You see, in 1796, about five-sixths of present-day Tennessee was still owned by Native American tribes. The Cherokee Nation still owned and controlled the Cumberland Plateau, all of present-day East Tennessee south and east of Kingston and most of southern Middle Tennessee. The Chickasaw Nation owned present-day West Tennessee.

As far as settlers were concerned, Tennessee consisted of two separate pieces of land divided by the “vast wilderness” of the Cumberland Plateau. The eastern half was known as the Washington District, named for George Washington. The western half was known as the Mero District. It was named for Esteban Rodrigues Miro (sometimes spelled “Mero”), the Spanish governor of Louisiana at the time.

Why?

You have to know a bit about Tennessee geography and history.

There are more than 30 rivers in Tennessee, and almost every one of them is part of the Mississippi River system. Any raft on the Harpeth, Duck, Cumberland, Holston or Tennessee rivers will eventually float to the Mississippi River and New Orleans. In the era before steamboats and the railroad, this meant that New Orleans was this area’s natural gateway to the sea.

In 1784, when present-day Tennessee was still part of North Carolina, the Spanish government closed the lower Mississippi River to the American traders, which caused great consternation to political leaders and tradesmen on the frontier. Four years later, at the request of citizens from the settlement now known as Nashville, the North Carolina legislature named the legal district for present-day Middle Tennessee the “Mero District.”

This may seem strange to us now, and it was confusing to many North Carolinians at the time. But early Nashville-area citizens were apparently trying flattery to convince the Spanish government to reopen the lower Mississippi to American trade. They were also trying to convince the Spanish to stop giving arms to Native American tribes that were fighting settlers.

Miro returned to Spain in 1791 and died four years later. But the name of the district remained in use when the Southwest Territory existed (1790–96) and during the first few decades in which Tennessee was a state.

So how often does a researcher of Tennessee history and culture run across the name “Mero” or “Miro”? Quite a bit, actually.

Articles about legal cases, treaties and military operations make frequent reference to the Mero District. An item in the 1794 Vermont Gazette about a skirmish with the Cherokee refers to Gen. James Robertson as being “of Mero District.” When Tennessee residents Robert and Sarah Slaughter petitioned for a divorce in 1802, they did so in the court of Mero District, as the newspaper item stated. A small item in the June 6, 1807, Virginia Argus newspaper reported that corn was far more expensive in Tennessee’s Mero District than it was in Knoxville.

One of Nashville’s first newspapers was called the Tennessee Gazette and Mero District Advertiser.

One of Nashville’s first newspapers was called the Tennessee Gazette and Mero District Advertiser. It was a four-page weekly, lasting from 1803 to 1807.

The Mero District is clearly marked on some of the early maps of Tennessee that are now preserved by the Library of Congress and Tennessee State Library and Archives.

One of the better-known short stories by Tennessee author Peter Taylor was called “In the Miro District.” Although the plot of the story has nothing to do with Tennessee history, the title references Middle Tennessee’s early name.

The surprising thing about all this is that, unless I’m mistaken, there is nothing (official at least) named for Miro today. The man for whom all of Middle Tennessee was named when Tennessee became a state no longer has a county, town, hill, valley or road named for him.

How’s that for being “erased” from history?