I recently learned that the tiny family cemetery near my office in suburbia is the final resting place of a Revolutionary War veteran.

The discovery got me thinking about burial locations of Revolutionary War veterans throughout Tennessee. I touched base with the Sons of the American Revolution and bought a book on the subject produced by the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1974. I compared the data in the book with information found on genealogical and cemetery websites.

The first thing to become clear was the fact that there can never be a complete list of American Revolutionary veterans. Frontier military units often left incomplete records (or no records at all). We simply don’t know about many of the soldiers killed in battle or who died on the way home from fighting.

Our best data about Revolutionary War veterans are the transcripts of those who came forward decades later to claim government pensions. But what about those who died before the government started distributing payments? What about those who didn’t ask for a pension?

Also, the term “Revolutionary War veteran” doesn’t just refer to those who fought at Kings Mountain, Saratoga, Yorktown and in other battles to the east. Since the British supplied arms to Native American tribes and encouraged them to attack Tennesseans on the frontier, everyone who left home to fight against the Cherokee, Creek and Shawnee during this era is considered an American Revolution veteran.

So, given these considerations, about how many veterans are we talking about? And what can we say about where they are buried?

The book “Roster of Soldiers and Patriots of the American Revolution Buried in Tennessee” lists the names of about 4,500 veterans interred in Tennessee. In some cases, the book cites the county in which the person is buried; in rare cases, the cemetery is included. But most of the time, the lead compiler (Lucy Womack Bates) was unable to find that information.

Cross-referencing names from the book with information on the internet, I concluded that most Revolutionary War veterans in Tennessee are buried in unmarked graves. We might know the county or the general area where the man was buried, but we don’t know the exact location.

There are, however, many Revolutionary War veterans buried in marked graves in small family cemeteries such as the one near my office. There is an even smaller percentage of Revolutionary War veterans buried in church cemeteries.

Having said all this, here are some cemeteries in Tennessee that have concentrations of Revolutionary War veterans:

-

The remains of 15 Revolutionary War veterans are buried at Zion Presbyterian Church Cemetery in Maury County. The first person to be buried in Eusebia Presbyterian Church Cemetery in Blount County was Joseph Bogle. Born in Ireland, he fought for a Pennsylvania regiment and died in 1790. Over the years, Eusebia Presbyterian Church Cemetery has developed an image as a resting spot for Revolutionary War veterans. A written account says there are 15.

- Zion Presbyterian Church Cemetery in Maury County also contains the remains of 15 American Revolutionary War veterans, at least six of whom fought at Kings Mountain, a decisive battle near the North Carolina-South Carolina border.

- Nashville City Cemetery contains the remains of at least nine Revolutionary War veterans, including James Robertson and John Cockrill.

- The Revolutionary War Graveyard in Dandridge contains five such veterans. The best known of them is Adednego Inman, who was wounded at Kings Mountain and later survived capture by the Chickamaugans.

- Five Revolutionary War veterans are buried at Weaver Cemetery near Blountville. The Sons of the American Revolution will be marking these graves at a ceremony on Friday, Sept. 15.

- Four Revolutionary War veterans are buried in Franklin City Cemetery in Williamson County. Here are some notable Revolutionary War veterans buried in smaller cemeteries:

- John Sevier, the first governor of Tennessee, is buried beside the Knox County Courthouse.

- Jonathan Meigs led a group of soldiers that burned 12 British ships and took 90 prisoners in a New York assault known as “Meigs Raid.” After the war, the federal govern-ment sent Meigs to Tennessee to be a federal agent to the Cherokee. He is buried at Garrison Cemetery in Dayton.

- Brothers Isaac and Anthony Bledsoe fought in the Revolution and migrated to Middle Tennessee after the war but were killed fighting Native Americans shortly after they returned home. They are buried at the family ceme-tery at Bledsoe’s Fort Historical Park in Sumner County.

- David Campbell’s first-person account of battle is featured in a book called “The Battle of Kings Mountain: Eyewitness Accounts.” “I was not more than twenty feet from [Tory Capt. Abraham] DePeyster” when the commander surrendered, Campbell later said. Campbell is buried in Leeville Cemetery in Wilson County.

-

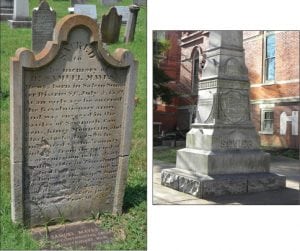

An impressive monument marks the grave of Robert Bean, Kings Mountain veteran who may have fired the shot that killed British Commander Patrick Ferguson. Capt. Robert Bean was also at Kings Mountain and may have fired the shot that killed British commander Patrick Ferguson. Bean’s grave can be found in Marion County at Bean-Roulston Graveyard.

- Pharaoh Cobb was a friend of Andrew Jackson who built one of Tennessee’s first horse tracks. His original gravesite had to be moved when the Tennessee Valley Authority created Cherokee Lake. You can now find the grave at Camp Davy Crockett, a Boy Scout Camp in Hawkins County.

I recommend you call your local Daughters of the American Revolution or Sons of the American Revolution chapter and research your corner of the state. What you will probably discover is that you have been driving right by a Revolutionary War veteran every day without realizing it. They are scattered all over the state as far west as Shelby County, which contains 19 such graves. In Kingsport, you will find the final resting place of James Gaines next to an apartment complex. A block from Cool-Springs Galleria in Williamson County is a small family cemetery that contains the remains of Revolutionary War veteran George Mallory.

Many history enthusiasts know that Nancy Ward of the Cherokee Nation warned early Tennessee settlers about an impending attack by the Chickamaugans. The trader she warned, Isaac “Big Shoulders” Thomas, fought in the American Revolution and is buried in the heart of Sevierville.

My favorite Revolutionary War grave is that of Joseph Greer, reportedly a giant of a man who fought at Kings Mountain and was chosen to deliver the news of the victory to Congress. The journey, mostly on foot, from the southern Appalachians to Philadelphia was treacherous. On at least one occasion, Greer hid in a hollow log to avoid being captured by the enemy. When he got to Congress Hall, the sergeant-at-arms tried to block Greer’s way as he entered the chamber. He pushed the officer aside, announcing to Congress that an army of frontiersmen had crushed Patrick Ferguson’s Tory army at Kings Mountain.

“With soldiers like him,” George Washington reportedly said, “no wonder the frontiersmen won.”

Joseph Greer is buried near Petersburg in Lincoln County. The last time I was there, the site was in good condition. But it isn’t easy to find. Do your research before you go, and don’t hesitate to ask for directions if you get lost.