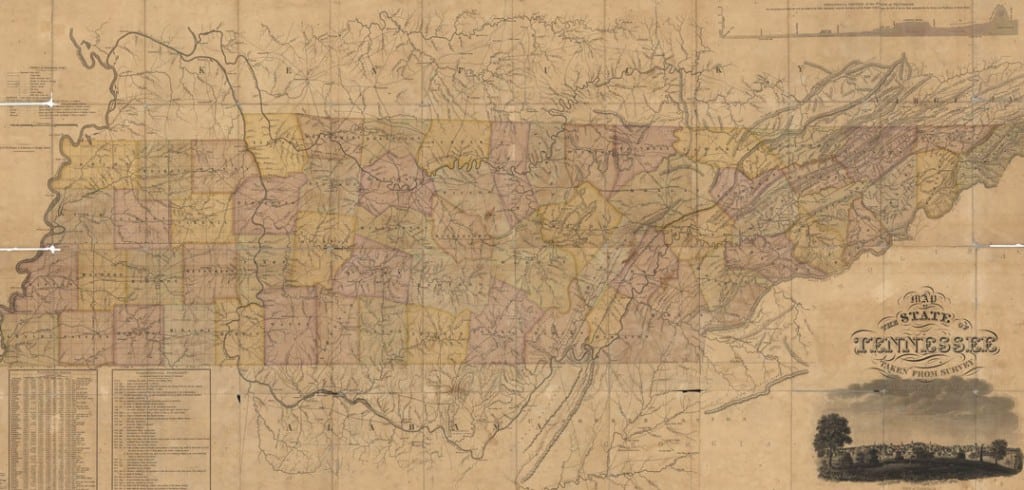

I have heard that one of the best early maps of Tennessee was produced by Matthew Rhea in 1832. So I found it on the website of the Tennessee State Library and Archives.

I didn’t necessarily expect this, but I have been mesmerized by Rhea’s map and the information in its legend. Here are some of the features I have observed:

- The phrase “Cumberland Plateau” does not appear on the map. However, the phrases “Cumberland Mountain” and “Table Land” do appear, several times, in the area now commonly referred to as the Cumberland Plateau.

- Tennessee had only 62 counties at this time. Consequently, many counties were physically larger than they are today.

- Previous county seats that no longer function as such — Monroe (Overton County), Washington (Rhea County), Montgomery (Morgan County), Reynoldsburg (Humphries County) and Troy (Obion County) — are clearly shown on the map.

- Because of the present-day location of the Natchez Trace Parkway, I was under the impression that the Natchez Trace started in the western edge of Davidson County. However, the map clearly shows that the road to Natchez began in Franklin and headed southwest through Gordon’s Ferry and past the grave of Meriwether Lewis, which is also on the map.

- I was surprised by the number of Indian mounds and prehistoric ruins that made the map. The site of Fort Loudon (destroyed in the 1750s) is mapped, as is Stone Fort (now known as Old Stone Fort) and “Mound Pinson” (now known as Pinson Mounds).

- The only feature in Nashville that made the map is the state penitentiary, which was at that time just west of town (present-day Charlotte Avenue).

- Reelfoot Lake, formed two decades earlier by the New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811-12, is not yet delineated on the map. The only indication that there is something unusual about the terrain in this part of the state is the use of the phrase “flooded land” over parts of Obion County.

-

Handwritten notations indicate obstacles along the Tennessee River’s route from Knoxville to where it crosses the Tennessee-Alabama border. The city of Chattanooga is not on the map. It was not formed until the Indian Removal Act was enforced in 1838. In fact, the only towns mapped along the Tennessee River south of Kingston are Washington (in Rhea County), Dallas (in Hamilton County) and the Indian village of Nicajack (which is usually spelled Nickajack), just north of where the borders of Tennessee, Alabama and Georgia meet. Today, none of these three communities exist. Washington is a ghost town. Dallas was flooded by the Tennessee Valley Authority. Nickajack, after being attacked by an army of settlers in 1795, would have been abandoned during Indian Removal in 1838.

- Memphis does make the map. So does the community of Randolph, 40 miles north along the Mississippi. At the time this map was created, Randolph and Memphis were in a competition to become the most important city along the river. Eventually, Memphis would win out. Today, Randolph is a ghost town.

- Having already done two columns on places whose names have changed in Tennessee history, I was startled at the number of place names that even I had never heard of. Manchester was known as Mitchellsville. Clifton was known as Carrollville. The list goes on and on and on.

- Someone hand-wrote on the map the location of every obstacle along the Tennessee River, starting in Knoxville and ending at the state line. According to the map, there were 50 such places, and the person who wrote them in apparently named most of them for settlers who lived in the area. Rhea County had seven (Gillespie’s, Walton’s, Well’s, Kelly’s, Lea’s, Hiwassee and one that I can’t read). Just downstream from present-day Chattanooga, this person indicates the exact locations of legendary Tennessee River obstacles such as the Suck, the Boiling Pot and the Skillet.

- There is no mapped community east of Winchester, west of Jasper and south of Manchester. Places in and near the south Cumberland Plateau such as Tullahoma, Cowan, Sewanee and Monteagle simply didn’t exist. The same can be said for East Tennessee communities such as Pigeon Forge, Gatlinburg and Cosby. As you see the open space on the map, it does make you wonder what the mountains looked like at that time.

-

Interesting inclusions on Rhea’s map are the locations of mills and forges across Tennessee. The map shows at least 16 forges in Carter County. The map shows the locations of mills and forges throughout the state. I have a feeling that Rhea was able to obtain more information from some counties than he was from others. It shows the locations of 10 mills in Hardeman County but only one in McNairy County and none in Henderson County. Meanwhile, no fewer than 16 forges made the map in Carter County in northeast Tennessee!

- When you look at the map, it is easy to understand why, a generation later, Confederate authorities decided to put a fort (Fort Donelson) just downstream from Dover in Stewart County. In addition to the Cumberland River, no fewer than five roads converge on Dover.

There is quite a bit of information in the legend, written on the bottom left corner of the map:

- In 1830, the two most populous counties in Tennessee were Bedford, which had 30,444 residents, and Maury, with 28,153 residents. Behind Bedford and Maury, the next seven counties ranked by population were Davidson, Williamson, Rutherford, Wilson, Smith, Lincoln and Giles.

- I was surprised to see that the population of East Tennessee was far less than that of Middle Tennessee. Within East Tennessee, that population was almost uniformly distributed. In fact, eight East Tennessee counties had populations of between 10,000 and 15,000 — Blount, Grainger, Greene, Hawkins, Knox, Roane, Sullivan and Washington.

- The three largest counties by population in West Tennessee were Henry, Hardeman and Madison, each with roughly 12,000 inhabitants. Shelby County had only 5,700 people.

- To my great surprise, Davidson County had more slaves than any other county in the state (11,629). Williamson was the only other county in the state with more than 10,000 slaves.

- In 1830, Tennessee had 4,510 free African-American residents. Davidson County had the largest number (473). This didn’t surprise me, but I was surprised to learn that, according to the map, there were 386 free African Americans living in Hawkins County, 263 in Grainger County and 204 in Sullivan County!

- The legend also lists the two or three principal exports of each county. Cotton, livestock and flour were the three listed most often. However, I was interested to see that horses were listed as a principal export for Sumner, Williamson, Davidson and Maury counties of Middle Tennessee — but not for any other county in the state.