I have been doing this column for more than nine years, and this is the first time I have written one about Sequoyah.

Why has it taken me so long? Because it’s hard to piece together — with any certainty — a coherent story of his life.

Sequoyah is one of the most important Tennesseans to have ever lived. He is also one of the most important members of the Cherokee Nation.

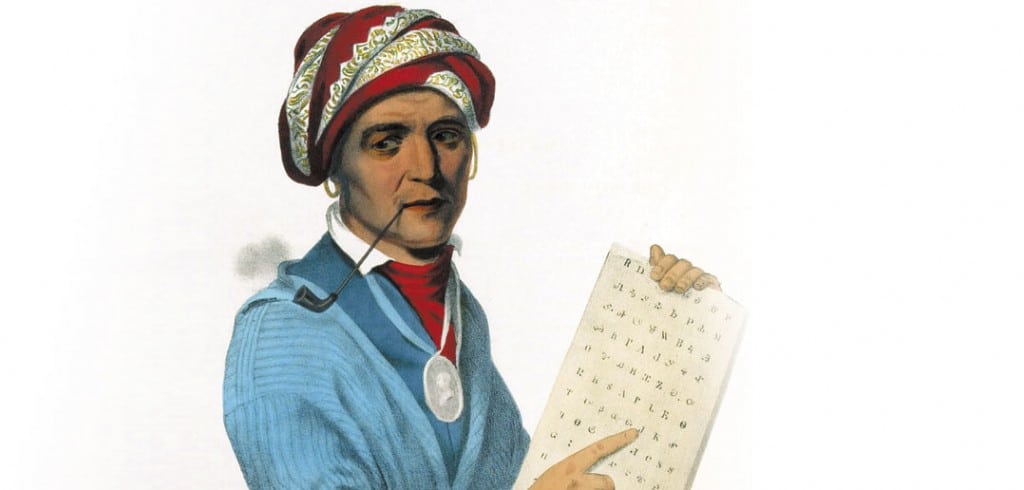

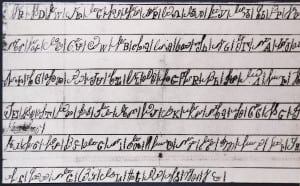

The man invented a written language by creating a syllabary, one symbol at a time, which allowed a person to write down any Cherokee word. This enabled the Cherokee people to become the first American Indians to have a written language. It was a remarkable achievement.

“Sequoyah is the only person in recorded history who created a writing system without first knowing a written language himself,” says Dr. Duane King, director of the Helmerich Center for American Research at the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

So why does this topic scare me?

Because much of what is written about Sequoyah contradicts itself. No matter what history book or children’s book you read, video you watch or website you click, you will find different accounts of Sequoyah’s life.

This is the great irony of Sequoyah. The man who invented a written language never wrote a story of his life. So, today, the stories about Sequoyah are all derived from a combination of oral tradition and conjecture. For instance:

We are not certain when Sequoyah was born. Various accounts of his life say he was born anywhere from 1760 until 1778! We do know where he was born: The location is in present-day Monroe County, where you’ll find the Sequoyah Birthplace Museum.

We are not certain who his parents were. Most sources indicate that Sequoyah’s mother was a full-blooded Cherokee named Wut-teh and his father a fur trader from Maryland named Nathanial Gist (a named that is often spelled “Guess”). But there are other accounts.

Within the Cherokee Nation, his father’s identity was not important. Sequoyah was a member of the Paint Clan.

The man went by two names. His Cherokee name was Sequoyah. His English name was George Gist (or Guess). This practice of having two names was very common at the time in the Cherokee world in which Sequoyah lived.

Sequoyah had a limp, but we don’t know why. Since the name Sequoyah means “pig’s foot,” many believe he was born with a disability. However, some accounts claim he was injured in a hunting accident or even hurt in military service.

“I think I have read 25 different accounts of why he limped,” says Charlie Rhodarmer, director of the Sequoyah Birthplace Museum in Vonore.

Like many other Cherokees, Sequoyah fought on the American side during the Creek War. His biographers have always assumed, therefore, that he was present at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend on March 27, 1814. However, “just what part Sequoyah played in the fighting is not on record,” claims Stan Hoig in the book “Sequoyah: The Cherokee Genius.”

Sequoyah was a silversmith and blacksmith. This means that, by standards of the time, he was well off and could buy household necessities as he needed them.

“I laugh at the idea you see in videos and read in stories about Sequoyah having to use knife and bark to create his language,” says Rhodarmer. “He would have been able to buy as much pen and paper as he would have liked, and I’m sure he did.”

Before he invented his syllabary, Sequoyah invented a numbering system. Although we don’t know for sure, it seems logical that the numbering system came out of his need to run his blacksmith business.

“I think he invented the numbering system as a way of keeping track of who owed him money and how much they owed him,” says Rhodarmer. “After all, he made his living doing things like making nails, jewelry and tools. He did so at a time when many of his customers couldn’t pay when they picked things up. So he had to keep up with all this.”

We don’t know exactly what led Sequoyah to invent his syllabary. Hoig’s book cites several separate explanations, all of which came from secondhand sources produced prior to the 1840s. According to some, Sequoyah said he originally got the idea watching American soldiers during the Creek War. However, a story in the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper published in 1828 said the idea came to Sequoyah when he overheard a conversation between young men who were talking about the ability of white men to put their language on paper.

“Mr. Guess, after silently listening to their conversation for awhile, raised himself, and putting on an air of importance, said, ‘You are all fools; why, the thing is very easy; I can do it myself,’ and, picking up a flat stone, he commenced scratching on it with a pin; and after a few minutes read to them a sentence, which he had written by making a mark for each word. This produced a laugh, and the conversation on that subject ended. But the inventive powers of Guess’s mind were now roused to action; and nothing short of being able to write the Cherokee language would satisfy him. He went home, purchased materials, and sat down to paint the Cherokee language on paper.”

We don’t know when Sequoyah moved from Tennessee to present-day Alabama. Because of this, no one really knows whether he was already working on the written language when he moved or whether the idea came to him after he left for Alabama.

Sequoyah had his share of detractors. All the accounts of Sequoyah’s life seem to maintain that many other members of the Cherokee Nation, including his wife, thought he was crazy. At some point, long after Sequoyah started working on his project, she reportedly destroyed all of his work. Sequoyah was frustrated, but he started all over again.

A book called “Old Frontiers” by John P. Brown attributes this quote to Sequoyah: “If our people think I am making a fool of myself, you may tell them that what I am doing will not make fools of them. They did not cause me to begin, and they shall not cause me to stop.”

Sequoyah’s demonstration of his written language to the Cherokee people was dramatic. Most accounts claim that Sequoyah, under suspicion of witchcraft, demonstrated his written language to tribal elders with the help of his daughter, Ayoka.

Here is an account of this demonstration that I found on www.cherokee.org, the official website of the Cherokee Indian Nation:

“Although the system was foolproof and easy to learn, Sequoyah and Ayoka were charged with witchcraft and brought before George Lowery, their town chief, for trial. Due to a Cherokee law enacted in 1811, it was mandated to have a civil trial before an execution was allowed to take place. Lowery brought in a group of warriors to judge what was termed a ‘sorcery trial.’ For evidence of the literacy claims, the warriors separated Sequoyah and his daughter to have them send messages between each other until they were finally convinced that the symbols on paper really represented talking.”

We do not know when Sequoyah died or where he is buried. We think he died in Mexico, where he was trying to find Cherokee people who had moved there from the United States.

Finally, I want to point out that none of this uncertainty about Sequoyah’s life detracts from the man’s significance.

In 1825, only four years after he had begun showing it to others, the Cherokee nation adopted Sequoyah’s writing system. With the help of missionaries, they began printing a newspaper in Cherokee called The Phoenix. Soon the literacy rate of Cherokees was higher than that of the American settlers in that part of the South.

Sequoyah, whom everyone had thought was crazy, was praised not only by his own people but also by the American government and newspapers around the world.

Sadly, Sequoyah’s writing system was not enough to keep the Cherokees from being forced to leave their homeland in what is now known as the Trail of Tears. By that time, Sequoyah had moved west to what is now Oklahoma.

For more about Sequoyah, visit the Sequoyah Birthplace Museum in Vonore. Its annual Cherokee Fall Festival will be held Saturday and Sunday, Sept. 12 and 13.