All smirking aside — when Tennessee first paved its highways, the most controversial stretch of road in the state connected Hamilton and Marion counties and was known as the Suck Creek Road.

First of all, I’ll explain the name: Prior to the damming of the Tennessee River, there were parts of the river just downstream from Chattanooga where the current sped up, created whirlpools and (if you weren’t careful) might smash your boat up against boulders. The vortex of this area where a creek tumbled into the river from Walden’s Ridge became known as The Suck, the creek as Suck Creek.

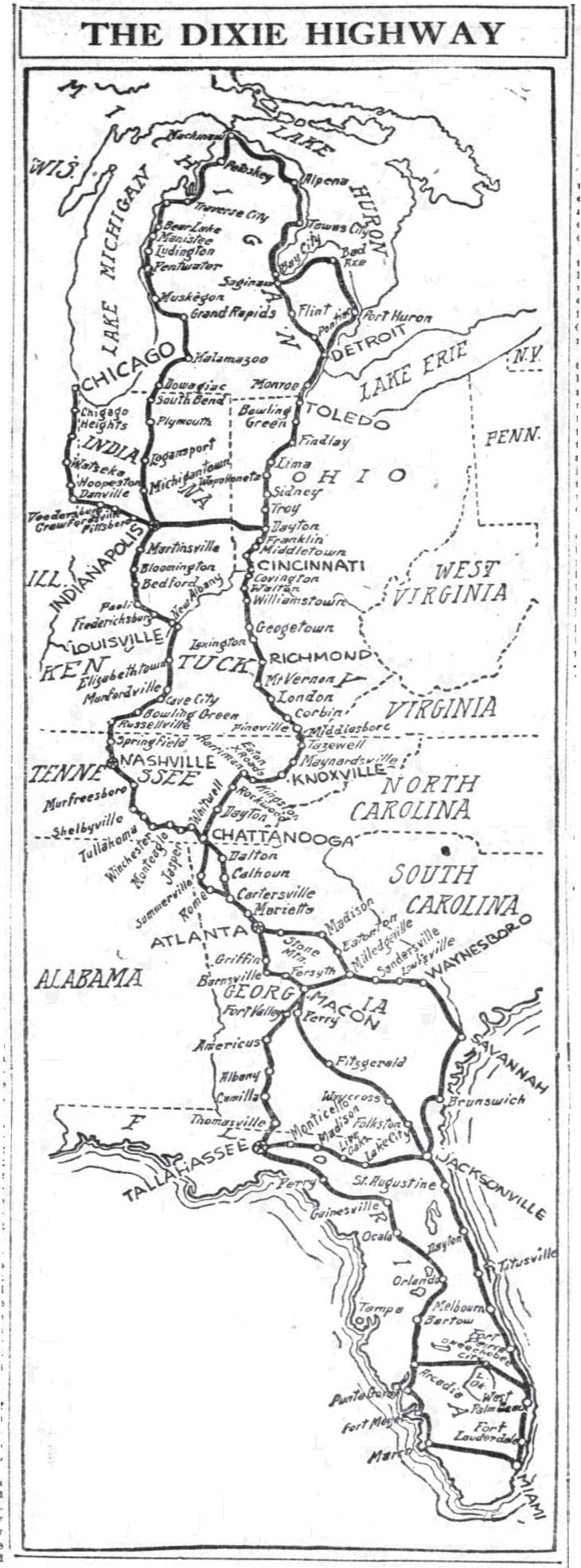

In 1914, national automobile enthusiasts planned two North-South highway routes that collectively became known as the Dixie Highway. One went through Chicago, Indianapolis, Louisville and Nashville on its way to Chattanooga. The other passed through Toledo, Cincinnati, Lexington and Chattanooga — making Chattanooga one of the few cities in America that contained both branches of the Dixie Highway.

In places where the terrain was flat, the Dixie Highway was paved without much trouble. But because of the mountainous terrain, the route northwest of Chattanooga created headaches and delays and ended up costing far more than originally projected.

There wasn’t a coordinated highway department in Tennessee in 1915. When the Marion and Hamilton County executives announced that a road along Suck Creek connecting Chattanooga to Whitwell was going to become part of the Dixie Highway, people got excited. “Tourists and local travelers will find Suck Creek route one of the most wonderful, entrancing thoroughfares in this part of the South,” the Chattanooga Times opined.

However, unlike most highways (which followed natural gaps in the terrain), parts of the Suck Creek route had never existed before, even as a path. The four miles from the Tennessee River to the top of Walden’s Ridge went along the deep Suck Creek gorge, requiring the blasting and removal of boulders the size of houses. Marion and Hamilton County officials brought in convicts from Brushy Mountain State Prison to blast the road the old-fashioned way.

The convicts (the vast majority of whom were black) arrived by train on June 19 and were marched through downtown Chattanooga chained together two-by-two, reminding old-timers of the horrible slave-trading coffles of antebellum days. “The convicts formed in line two abreast,” the Chattanooga Times reported. “The inside hand of each man was manacled to a chain which ran the full length of the line, leaving the outside arm of each free to carry his bundle of blankets and clothing.” Inmates were transported by boat to their temporary home near the mouth of Suck Creek.

In this panoramic view beside Suck Creek, the road can be seen in the far right of the photo.

Some 175 inmates worked on the road for six months and then were sent back to Morgan County. However, the road itself wouldn’t be ready for use by automobiles for years. Why? I’m guessing that the problems were both engineering and financial in nature. This particular stretch of road — up a steep mountain and past a rushing creek — wasn’t something that men with picks and shovels could clear, at least not in six months.

This map from the Jan. 4, 1917, Chicago Tribune shows the two branches of the Dixie Highway, then being developed.

A lot of the problems had to do with the fact that the expensive part of the road (along Suck Creek Gorge) was in Marion County. Meanwhile, the residents of Hamilton County, which had more people and a much larger tax base, wanted the road more than the people in Marion County, which was rural and mostly destitute. “The public is thoroly (sic) indignant over this entire Suck Creek proposition,” the Sequatchie Valley News opined. “It’s a disgraceful waste of public money, should have never been started and ought now be stopped.”

In fact, the Tennessee General Assembly temporarily “transferred” about two miles of Marion County to Hamilton County so its taxpayers could pay to create a road in another county.

Along came World War I and the influenza epidemic that followed it, and after five years, the road still wasn’t finished. By that time, the cost of it had ballooned to several times its original estimate. Progress on the road finally resumed in 1920 when the state sent in more inmates and a 50,000 pound steam shovel to finish it.

Somehow, someway, they got the road completed. It was officially opened in May 1921 when the Dixie Highway Association held its annual meeting in Chattanooga. At that time, the scenery along it was declared “not surpassed east of the Rocky Mountains.”

Throughout the early 1920s, you will find mention of Tennessee’s famous and beautiful Suck Creek Road in newspapers all over the South and Midwest. Locally, in Chattanooga, two of the discussions stand out.

One is the name. It was proposed — and rejected — that the stretch be rechristened as “Cherokee Road.”

The other discussion had to do with the preservation of the road’s natural beauty. One writer for the Chattanooga News pointed out that the beauty along the road was unique and, if preserved, would evolve into a tourist attraction of its own. If it wasn’t protected, he feared, “timber men and coal operators will destroy the beauty of the road.”

So what became of this nationally publicized stretch of highway? A few weeks ago, I drove to Chattanooga to find out.

One of the scenic views from Suck Creek Road on the other side of Walden’s Ridge from Chattanooga.

The first few miles, which take you from the city along the Tennessee River valley, have heavy industry for a while and then a series of riverside houses along the way.

The four-mile stretch up Walden’s Ridge along Suck Creek could be a beautiful drive with stops along the way where tourists could view the rushing creek and waterfall below. In fact, it apparently used to be. However, I’m sorry to report that most of the pullovers along the road have been made inaccessible, probably because so many people were dumping trash over the embankment.

Once you get to the top of Walden’s Ridge and head toward Whitwell, Suck Creek Road proceeds as do many highways through East Tennessee — with some pretty spots and some not so pretty.

In any case, from one end of Suck Creek Road to the other, there is no longer an indication of the long, drawn-out story behind the route or its fabled connection to the Dixie Highway. There has apparently been little effort to capitalize on the remarkable natural beauty that once dominated it. I’m afraid the Suck Creek Road is just another semideveloped stretch of steep Tennessee highway with a largely forgotten backstory.