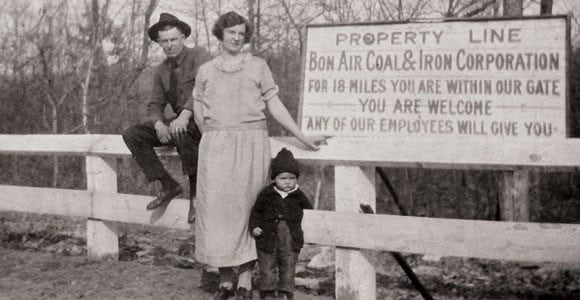

In the 1920s, there was a sign along Highway 70 in White County that read:

Property Line Tennessee Products Corporation For 18 miles, you are within our gate You are welcome Any of our employees will give you information or necessary assistance.

Today, it is hard to imagine a single entity other than the government owning 18 contiguous miles of land. But the Tennessee Products Corporation and its predecessor company, the Bon Air Coal and Iron Corporation did. It also owned land in Hickman, Lewis, Wayne and Hamilton counties.

The number of acres only begins to tell the story, however. Tennessee Products owned the mines as well as everything in the towns near the mines. The company owned the houses where their miners lived, the stores in which they shopped, the newspapers they read and even the cemeteries where they were buried.

Looked at in that way, the Tennessee Products Corporation might have been one of the most powerful companies in Tennessee history.

There are also things about this now-forgotten company that are fascinating:

- In most cases, the towns owned and operated by it are gone; nothing is left of them except a place name, a few stories and photographs.

- The man who organized the company had previously gone to prison.

- Two if its main investors were men whose names we associate with the early days of professional baseball.

- The most famous person to have been born on Tennessee Products Corporation property was the son of a black coal miner.

Having said all this, we know a lot less about the Tennessee Products Corporation than we should. Here is what I have been able to put together.

‘Big Bill’ Cummins

There were small mining operations all over Middle Tennessee before the Civil War. Mining grew on a much larger scale after the war because of the expansion of railroads and because companies based in the North were investing large amounts of money in the South.

By the 1880s, the Bon Air Coal and Lumber Company owned thousands of acres, several mines and several mining towns in White and Cumberland counties. In 1897, that company bought some mines in Hickman County. Eventually that company expanded until, on the verge of World War I, it owned more than 50,000 acres.

Then, in 1917, William Cummins took over the business. People who live in Nashville recognize this name because there is a giant warehouse (Cummins Station) next to the Union Station Hotel named for him. However, many people don’t realize that “Big Bill” Cummins had a fall from grace after he left Nashville.

You see, after years as a successful grocery wholesaler and real estate developer in Nashville, Cummins accepted a job as the chairman of New York’s Carnegie Trust Company. The trust company failed, and Cummins was accused of misappropriating $140,000. Cummins was convicted and served three years in prison before the governor of New York pardoned him.

Cummins came back to Tennessee and was welcomed with open arms. He also still had the friendship of wealthy men in the North — including William Wrigley of Chicago and Jacob Ruppert of New York. (Today, baseball fans know Wrigley as the longtime owner of the Chicago Cubs and Ruppert as the former owner of the New York Yankees.) With these two men as his backers, Cummins took over Bon Air Coal and Iron.

Company baseball

In 1919, the Bon Air Coal and Iron Corporation built a wood distillation plant in the Hickman County town of Lyles (distillation is used to produce chemicals for the waterproofing of airplanes; it produces charcoal as a byproduct). In addition to the plant, Bon Air Coal and Iron created an entire community around it. It was called Wrigley, after you-know-who.

If you want to read all about life in these communities from this era, a detailed source of information is available. The company produced a newspaper called the Bon Air Hustler that it distributed to readers in its mining towns, which included Bon Air, Ravenscroft, Eastland and Clifty (White County); Wrigley, Lyles, Goodrich and Aetna (Hickman County); Ruppertown and Allens Creek (Lewis County); and Collinwood (Wayne County).

The Bon Air Hustler makes it sound as if life was peachy, filling its columns with happy stories about the towns it served. But it is important to remember that life as a miner and in a mining family was austere and tough. In most of these communities, miners were paid in scrip and lived in small houses owned by the company. They did not have much in the way of health care. (Those in White County largely relied on Dr. May Wharton, the legendary “Doctor Woman” who made housecalls from Pleasant Hill.)

Miners worked six days a week and, during summer months, played organized baseball against teams from other mining communities. People who grew up in these towns later said that they took these baseball leagues very seriously. The teams were well equipped to play ball because Wrigley and Ruppert appear to have donated leftover major league uniforms to the coal mining league teams.

I’m sorry to say that if you go back to the places where these communities were, you won’t find very much left of them. In White County, a wonderful group of local history buffs and educators organizes a history fair and bus tour every May of communities such as Ravenscroft, Clifty and Eastland. But most of what you see on the tour is vacant land where stores, houses and mines used to be located.

Czech tombstones and Carl Rowan

It is largely because of photographs and stories (written and oral) that we are able to remember the communities and the lives of the people who lived in them. On the White County bus tour, we drove through the site of a now largely abandoned community called Ravenscroft. The tour guide took us to an area that she said was once the black part of Ravenscroft and pointed out that it was the birthplace of Carl Rowan, a high-ranking member of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations and a national op-ed columnist in the 1970s and 1980s.

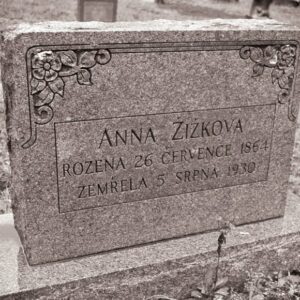

Just down the road we stopped at a cemetery in a Putnam County community known as Glades Creek. I got out to take photos of tombstones with Czech writing on them. Early in the area’s mining history, I learned, the companies brought in experienced miners from Czechoslovakia. The tombstones are the last remaining sign of this corporate strategy.

In 1926, the Bon Air Coal and Iron Corporation merged with the Chattanooga Coke and Gas Company and the J.J. Gray Foundry of Maury County and became the Tennessee Products Corporation. The publicly traded Tennessee Products Corporation, according to its corporate literature, sold timber, coal, coke, natural gas, wood alcohol, charcoal and many other byproducts of coal to, among other companies, DuPont, Eastman Chemical and Bethlehem Steel.

The Tennessee Products Corporation’s quaintest product was a breath mint called “Breethem,” containers of which can be bought on eBay.

It was during the next decade or so that the Tennessee Products hit its apex in terms of size, at one time owning more than 100,000 acres of land, including large parts of several counties. It was one of the largest employers in Tennessee in the late 1920s and 1930s — even though its corporate headquarters in Nashville’s Stahlman Building was small.

Tennessee Products Corporation declined rapidly starting in the late 1930s. I believe it did so because of two major reasons: the deaths of Wrigley (in 1932) and Cummins (in 1939) and a huge reduction in demand for coal because of the arrival of the Tennessee Valley Authority in the 1930s and 1940s and natural gas lines in the 1950s.

In spite of this, Tennessee Products continued to operate a charcoal plant in Wrigley until the mid-1960s. Today this is one of two Environmental Protection Agency-administered superfund sites associated with Tennessee Products; the other is a coke factory in Chattanooga.

As best I can tell, Tennessee Products’ huge tracts of land were sold to the highest bidder, whether that be another company or a co-op. Most of its mines were covered up, and the thousands of homes and store buildings that were once operated by the company were torn down or eventually burned.

Today, little is left of the Tennessee Products Corporation and its culture, other than place names and photographs.

Thanks to the Bon Air Mountain Historical Society and to Mike Capps for all the work they have done in unearthing information on these companies and communities.

There’s more on the Web

Go to tnhistoryforkids.org to learn more tales of Tennessee history.