Tennessee became a state on June 1, 1796. Today, when students read this fact in the history books, it seems inevitable.

However, here’s a statement that might start an interesting discussion about the subject: You could have made a good argument back then that Tennessee wasn’t ready to become a state.

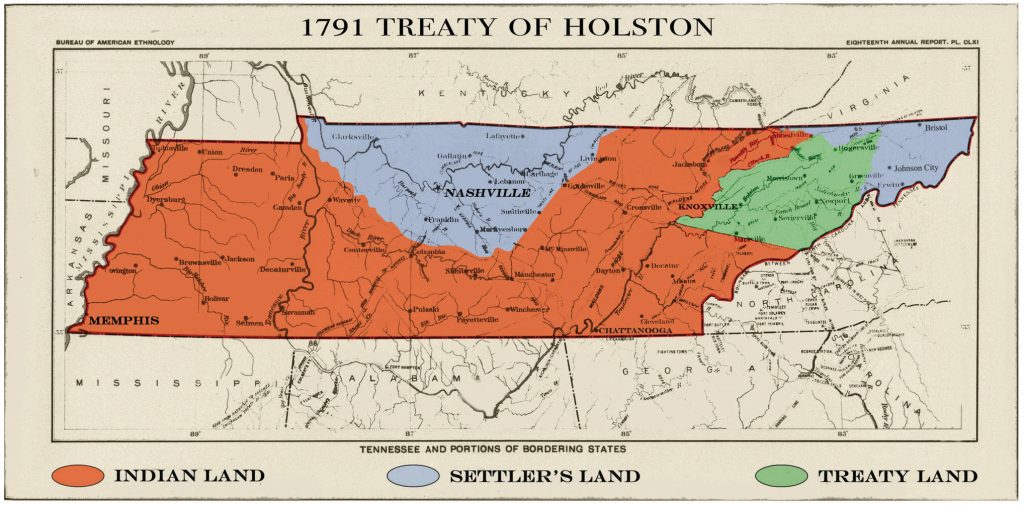

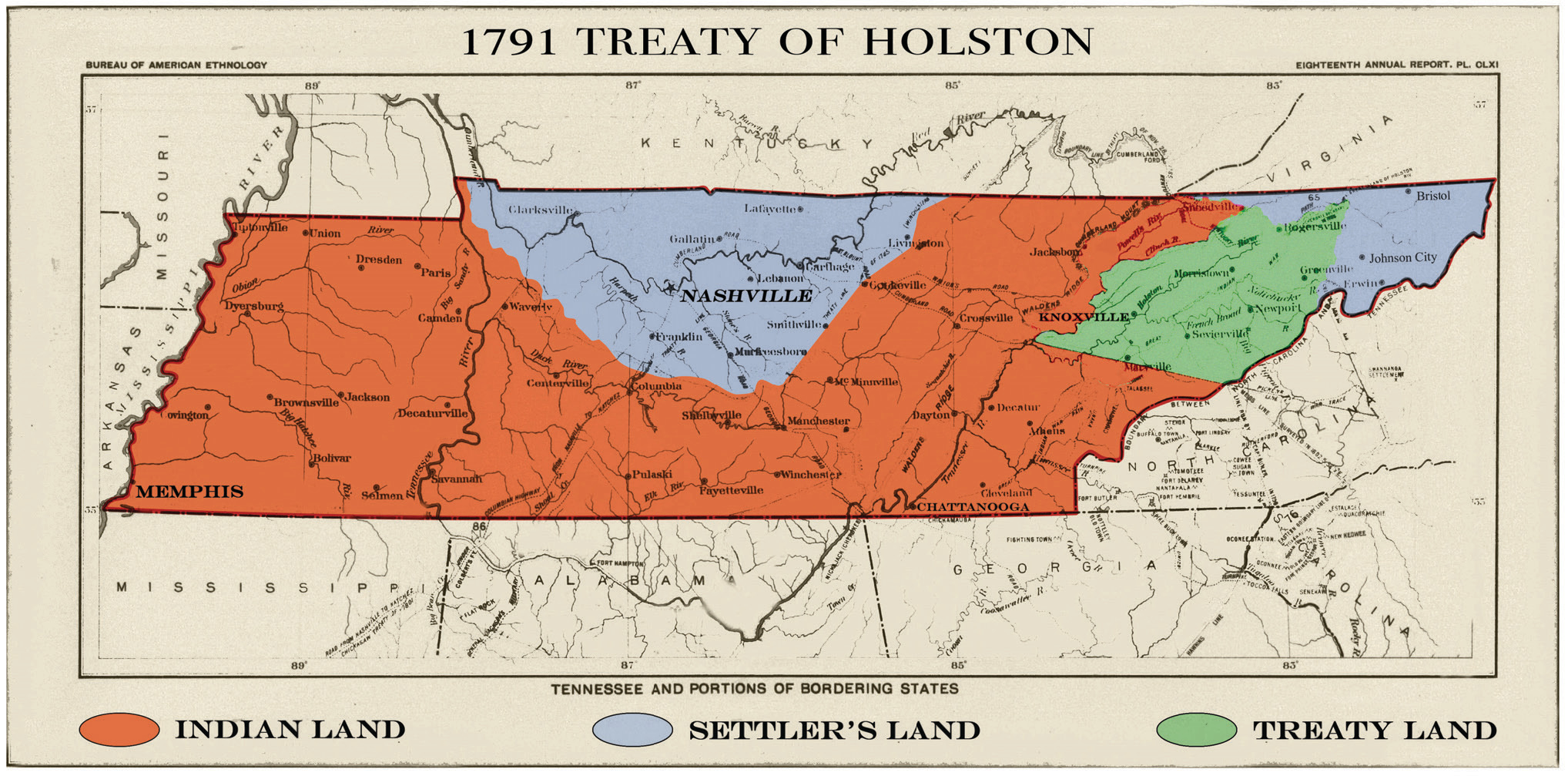

In 1796, about five-sixths of present-day Tennessee was still owned by Native American tribes. The Cherokee nation still owned and controlled the Cumberland Plateau, all of present-day East Tennessee south and east of Kingston and most parts of Middle Tennessee that were drained by the Tennessee River. The Chickasaw nation owned all of present-day West Tennessee.

As far as white settlers were concerned, Tennessee consisted of two separate pieces of land, divided by the “vast wilderness” (to use the vernacular of the time) of the Cumberland Plateau. The eastern part was known as the Washington District; the western part (present-day Middle Tennessee) was the Mero District.

The Knoxville Gazette was the only newspaper in Tennessee back then. Here are some tidbits about life in present-day Tennessee that I found from looking through issues of it:

The road along the Cumberland Plateau was so dangerous that most people only traveled it with military escort. Every so often, these escorts left Fort Southwest Point (present-day Kingston) heading west and Fort Blount (present-day Jackson County) heading east. “On the 20th of October next,” reported the Gazette in the summer of 1795, “the annual escort through the wilderness for families will leave the blockhouses at Southwest point.” Nevertheless, people still tried to cross without military escort, and they sometimes didn’t make it. Thomas “Big Foot” Spencer was killed near Crab Orchard while traveling the road in April 1794.

This map, created by the staff of the Tennessee State Museum, shows how most of present-day Tennessee was owned by American Indian tribes (Chickasaw and Cherokee) after the 1791 Treaty of the Holston.

The news was full of stories of violence among settlers and Native Americans. The January 1795 Gazette reported three deaths on the Harpeth River west of Nashville. A February 1795 issue contained news of the death of George Man of Sevier County. In March 1795, the Gazette reported two deaths at Joslin’s Station near Nashville. A May 1795 issue reported several acts of violence, including the death of a soldier “on duty at the ford of Cumberland” (Fort Blount).

The Gazette published several items reminding readers of why Native Americans were fighting in the first place. On Jan. 8, 1795, Southwest Territory Gov. William Blount issued a proclamation ordering all settlers who had illegally moved into the area known as Powell’s Valley to leave immediately and “in case of a refusal to neglect to obey this command, that they will answer the same at their peril.”

As a reminder of just how unorganized East Tennessee was at the time, the Gazette contained stories about East Tennessee communities that were being conceived and laid out for the first time. The Sullivan County community of Blountville was announced in July 1795. The purchasing and laying off of lots in both Maryville and Sevierville were reported in October 1795. Greeneville was announced two issues later.

What did this search through early issues of the Knoxville Gazette lead me to conclude? Two main points:

One is that it is misleading to use a current map while teaching about Tennessee becoming a state. Settlers controlled so little of present-day Tennessee that the modern map is inappropriate. It is also important to remember that even within East Tennessee, many communities and county seats were either new or still being established.

The other point that needs to be emphasized is why Tennessee’s early inhabitants were anxious to become a state in the first place. When Tennessee became a state, its residents were hopeful that the federal government would do more to help them militarily against Native Americans.

In any case, Tennessee did become a state, using the steps spelled out by the new U.S. Constitution and Congress. In the fall of 1795, the government of the Southwest Territory held a census and found it had a population of more than 77,000 — far more than the 50,000 required for statehood. A referendum showed that about three-fourths of eligible voters favored statehood.

A replica of Fort Southwest Point now exists in Kingston. Tennessee History for Kids photo

Blount, the territorial governor, called a convention that met in the spring of 1796. That convention of 55 delegates drew up a state constitution.

Tennessee’s new constitution was similar to the one the nation had just adopted. It called for three branches of government: an executive branch led by a governor, a judicial branch led by a state supreme court and a legislative branch consisting of a house and a senate. It didn’t go into much detail, especially in regards to how the court system should be organized. However, it was, in the opinion of Thomas Jefferson, the “least imperfect and most republican of the state constitutions.”

These 55 delegates chose the name of the new “free and independent state.” It came from Tanase, a Cherokee village in present-day Monroe County.

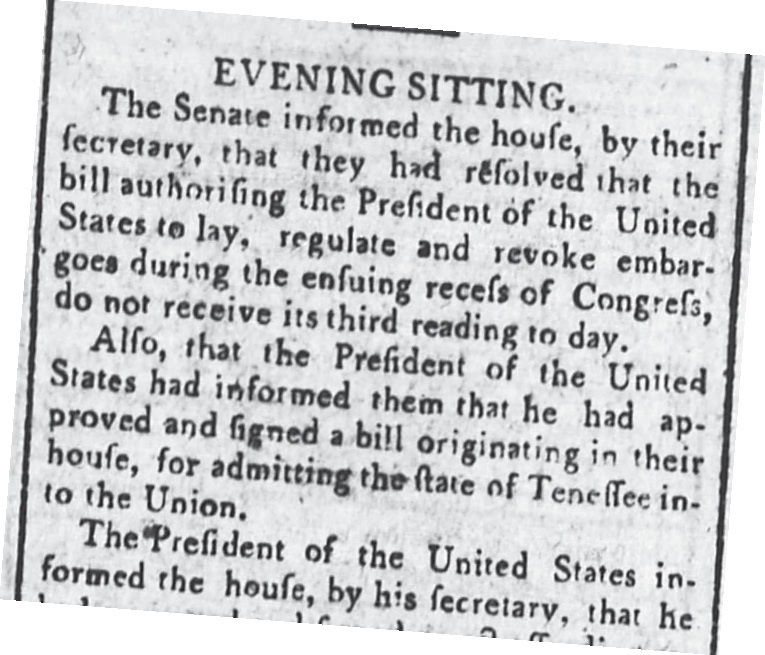

June 4, 1796, Philadelphia Independent

Congress, meeting in Philadelphia at the time, approved statehood on June 1, 1796. A few days later, the (Philadelphia) Independent Gazetteer contained only one sentence that mentioned the 16th state:

“Also, that the President of the United States had informed them that he had approved and signed a bill originating in their house, for admitting the state of Tennessee into the Union.”

A few months later, John Sevier was elected Tennessee’s first governor. Blount and William Cocke were elected to be Tennessee’s first U.S. senators.

And who was Tennessee’s first member in the U.S. House of Representatives? It was a tall, lanky man from Nashville who was still little-known in many parts of the state.

His name was Andrew Jackson.