A literal paper trail pieces together a dark chapter in our history and reminds us never to repeat it again.

The government of Nashville owned 26 slaves. chancery court officials routinely sold slaves at practically every courthouse in the state. Companies ranging from cotton mills to railroads advertised for slave labor. The state of Tennessee gave away slaves as young as 3 years old in a lottery. A slave died in the construction of the Tennessee State Capitol.

These are just some of the discoveries I made during a journey that started with a column and ended with a book.

Back in October, I went to the Tennessee State Library and Archives in Nashville. At the time, I thought I would write a column about the first few issues of the Knoxville Gazette newspaper, which debuted in 1791. I thought the column would be funny.

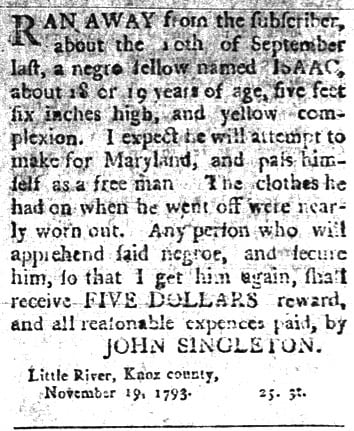

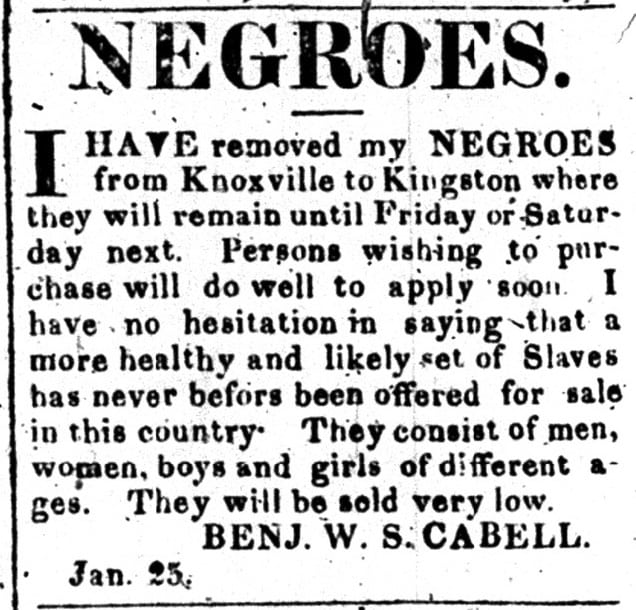

However, when I pulled up the first few issues of the Gazette, I noticed something far from amusing. The Gazette had slavery-related advertising in every issue: runaway slave ads, items announcing the sheriff’s capture of runaway slaves, slave sale ads and “slave wanted” ads. This took me by surprise; after all, those of us who write about Tennessee history don’t often talk about slavery in East Tennessee in the 1790s.

I looked through every issue of the Gazette and made copies of every slave-related ad. I then looked through the Tennessee Gazette, printed in Nashville from 1800 to 1808, and every issue of the Nashville Whig, printed from 1812 to 1849. I did the same with the Jackson Gazette, Memphis Enquirer, Clarksville Jeffersonian, Athens Post … and the list goes on and on.

I eventually looked through every antebellum newspaper I could find. I organized the ads into categories and created spreadsheets with notes on their contents. To learn more about the subject, I bought several books on slavery, the best of which was one titled “Slave Trading and the Old South,” printed in 1931. I kept digging.

I eventually wrote a book called “Runaways, Coffles and Fancy Girls: A History of Slavery in Tennessee.” It contains, among other information, details about how slavery made its way into Tennessee in frontier times until it was abolished during the Civil War. It includes chapters on the slave trade and how slavery was embedded in the economy. It also contains data from no fewer than 906 runaway slave ads that document the flight of more than 1,400 Tennessee slaves, starting in 1791 and going until 1864.

Here are some of the more notable revelations:

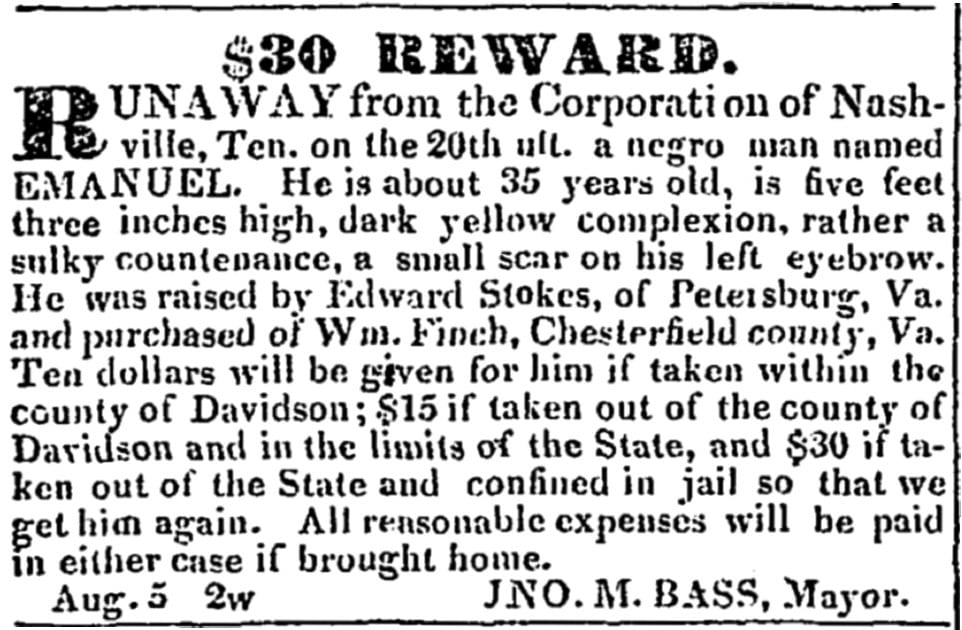

- In 1830, the government of Nashville paid a slave trader named William Ramsey $12,000 to buy slaves on its behalf. Ramsey went to Virginia and bought two dozen slaves: Ben, Emanuel, Jim, Frank, Lewis, Moses, Salem, Anthony, Charles, Lucinda, Lilburn Henderson, Allen, Jim, Moses, Allen, Isaac, Vincent, Peter, Bob, Granville, John, Isaac, John and Jim. Those 24 slaves were taken away from their families and herded to Middle Tennessee (probably chained together in what was then referred to as a slave coffle). Nashville’s government later bought two more slaves named Daniel and Betsy and used its 26 slaves to perform such tasks as building the city’s first waterworks. At least twice, some of these slaves tried to escape. The mayor of Nashville purchased runaway slave ads in hopes of tracking them down.

- In 1836, the government of Tennessee organized a lottery to raise money for internal improvements (mainly road construction). Lottery prizes included assets such as land, a farm, steamboats and five slaves: a 45-year-old man named Charles, a 43-year-old woman named Nancy and three girls named Matilda (12), Rebecca (11) and Maria (6).

- Slaves were often sold as the result of lawsuits, the dispensation of an estate or the financial over-extension of a slaveholder. These sales were carried out by chancery court clerks and masters at slave sales that were announced in public notice ads. I found 163 of these events that accounted for the sale of 1,199 slaves in counties ranging from Blount to Lincoln to Shelby.

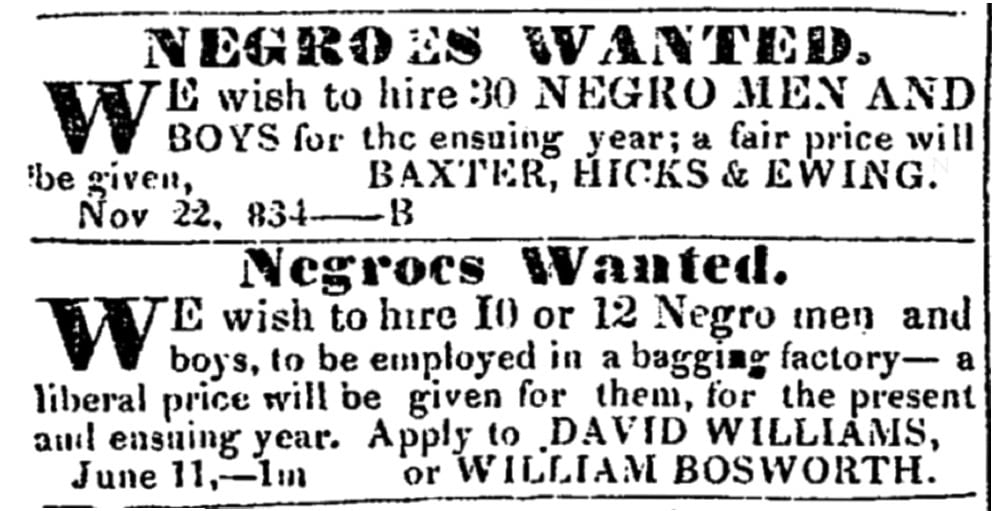

- The leasing of slave labor was so common that companies ran ads to hire slaves. Under this arrangement, the slave would work for the company that leased him or her, and the slaveholder would receive the wages. Through this method, families hired slaves to do domestic work. Construction firms hired slaves to be carpenters, bricklayers and painters. Cotton mills, iron foundries and tobacco processers manned their factories with slave labor. When railroads were built in Tennessee, many of them hired slaves. The practice of “hiring out” slaves became so common that there were people in Nashville and Memphis who made their living as “temp agencies for slaves,” if you will.

- Isaac Franklin — possibly the most successful professional slave trader in American history — was from Middle Tennessee. He owned a business called Franklin & Armfield, which bought slaves in Virginia and Maryland and sold them in Louisiana and Mississippi, transporting most of them by ship. Franklin & Armfield bought and sold upwards of 13,000 slaves in the late 1820s and early 1830s. Some of the money it made was used to pay for Nashville’s Belmont Mansion as well as the early buildings at the University of the South at Sewanee.

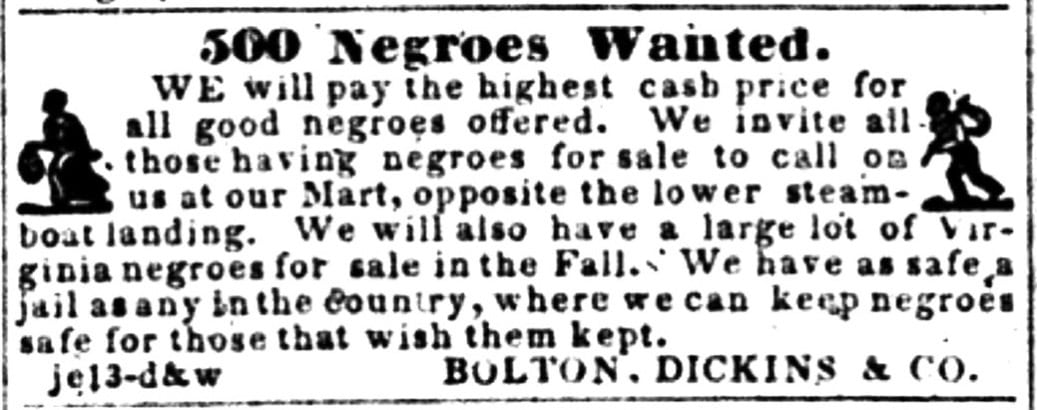

- Professional slave traders came and went in most Tennessee cities while Memphis and Nashville had well-established professional slave-trading industries. Although the people who ran these companies varied from year to year, you can follow the evolution of each city’s slave traders through newspaper advertising from the 1820s until the Civil War. Bolton, Dickins and Company of Memphis was probably the largest slave-trading firm in the city’s history, and Nathan Bedford Forrest was its most famous slave trader.

- On Oct. 21, 1848, a slave who had been hired by architect William Strickland died during the construction of the Tennessee State Capitol. “A sad accident happened on Saturday, about noon, at the Capitol quarry,” the Republican Banner reported. A negro man belonging to Mr. Baldwin, whilst at work there, received a blow from a lever, by some mismanagement, which broke his spine.”

- The fact that slave families were separated from each other is reflected in slave sale ads and runaway slave notices. When slaves ran away, the purchaser of the runaway ad often predicted that the slave would head in the direction of the family from which he or she had been separated. So, when two slaves named John and Sam ran away in 1822, slaveholder David Harding pointed out, “I purchased John in Maryland and Sam high up in Virginia. There is no doubt what they are aiming to get back again.” When a slave named John ran away in 1833, his slaveholder, Elisha Clampitt of Jackson County, predicted, “He will probably aim for Nashville” since “his mother belongs to Mr. Matthew H. Quin” of that city and because he “was raised by Mr. Jos. T. Elliston,” also of Nashville.

The separation of slave families is also documented in advertisements related to the sale of slaves. Slaveholders often indicated in such ads their intentions to sell some members of a slave family (such as children) but not others.

One more thing about my research and discoveries: There are old newspapers held by local libraries and collectors that are not on microfilm at the Tennessee State Library and Archives. I did the best I could, but I didn’t discover everything.

“Runaways, Coffles and Fancy Girls: A History of Tennessee” is available wherever books are sold. You can also purchase signed copies on the website www.clearbrookpress.com.