Had the Nashville lynch mob succeeded, American history might have turned out differently.

There might not have been a “Know-Nothing” political party. There might not have been a “Buffalo” Bill Cody, at least not in the eyes of the public. In fact, the image of the American West might have been different if someone hadn’t cut the rope that would have hanged Edward Zane Carroll Judson in front of the Nashville courthouse.

As luck would have it, however, Judson survived the attempt on his life, although his brush with a group of angry Nashville residents crippled him for the rest of his life.

Judson was better known by the pen name Ned Buntline. Author, journalist, activist, self-promoter and showman, he was famous for different things at different times of his life. You can learn a lot about Buntline at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming. “Poor people read his (Buntline’s) books and wanted to go West,” says a 1951 book about him.

Buntline’s name even turns up on weaponry (Colt once allegedly produced a revolver with a 12-inch barrel known as the “Buntline Special”) and in Mark Twain novels (at one point, Tom Sawyer pretended to be in one of Buntline’s pirate novels).

Judson was born in 1821 in upstate New York. At 17, while a midshipman in the Navy, he wrote a story for a national magazine called The Knickerbocker. He gave himself the pen name Ned Buntline (the word “buntline” is a nautical term that refers to the rope at the bottom of a square sail). Other stories followed, and soon he found a readership for his tales about pirates and other adventures at sea.

When Buntline got out of the Navy, he started his own publication called Ned Buntline’s Magazine. People read it, but it later folded, as did a successor publication, as did another successor publication.

In 1845 he and his wife, Seberina Escudero, moved to Nashville — drawn there for two reasons. One was cultural; at the time Nashville was the political center of what was still, culturally at least, the American West. The other reason was personal; Buntline had a connection to Nashville Banner editor Felix Zollicoffer.

A man who married at least six times, Ned Buntline always did have a way with the ladies. During his short stint in Nashville, he allegedly got involved with someone else’s. At the time one of the prettiest women in town was Mary Porterfield, the teenage wife of an auctioneer named Robert Porterfield. Married or not, Ned, Judson or whatever he was called was quite the figure around town, and he caught her eye.

In details that later came out in court, Ned started to woo the young lady — by talking to her and on at least one occasion sending her a poem. Lots of rumors were flying around about the two of them at the Trabue boarding house, where Mr. and Mrs. Porterfield were living at that time. Ned and Mrs. Porterfield were seen together in suspicious circumstances — once in an alley beside a church.

Robert Porterfield met Ned and warned him to stay away from his wife. The warning went unheeded because a few days later — on March 11, 1846 — a minister spotted Ned and Mrs. Porterfield together in the graveyard in which the Porterfield’s infant daughter had been buried. They were “standing face to face very near each other and apparently engaged in close conversation,” the minister later testified.

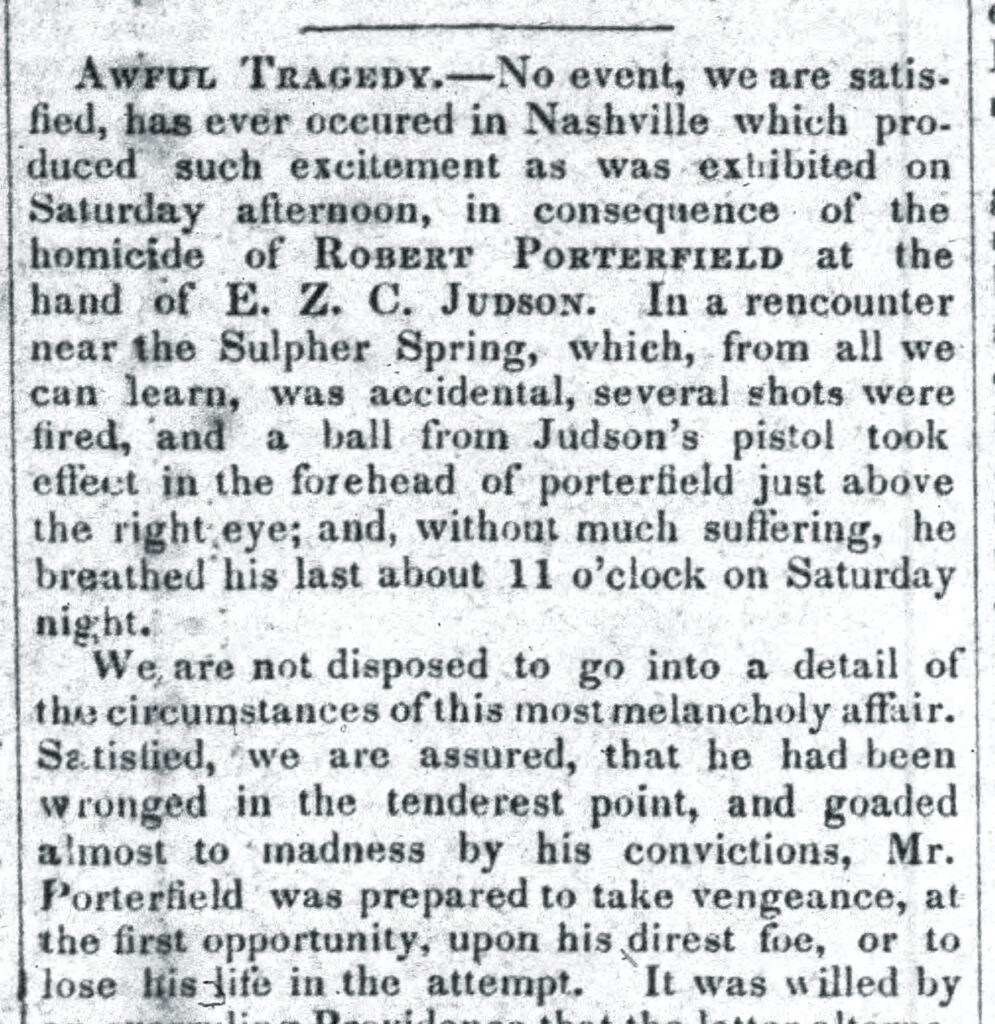

A few days later, Porterfield found Ned and started shooting at him. Ned fired back and struck Porterfield with a bullet right above his eye. Hours later, Buntline gave himself up to the local sheriff.

In those days law and order were relative concepts. When the hearing took place, Porterfield’s brother barged into the courtroom and opened fire on the accused. Buntline fled the courthouse and into the City Hotel across the street. A mob dragged him to jail.

That night, Robert Porterfield died of his wound. The mob reassembled and, as an eyewitness later said:

“When the mob rushed into the jail, they knocked (jailer Louis) Hord out of a rocking chair and secured the keys when he said, ‘For God’s sake, don’t let all the prisoners out.’ Three of the mob entered Buntline’s cell. While one caught him by a leg, another seized him by the collar. A third, placing his foot on Buntline’s neck, was about to fire when the jailer pleaded with him not to kill him there. Buntline was then dragged pell-mell into the street. He was then permitted to say his prayers, and on finishing pulled a ring from his finger, handed it to a minister to be sent to his father at Pittsburgh. The crowd then halloed, ‘Take him on,’ and they did so.”

A rope was tied around Buntline’s neck, and he was hung from an awning post on a public square. Before his neck broke, however, the rope snapped and his body tumbled back to the ground. “The rope was cut by a friend,” Ned later wrote. (An 1886 account of the incident claimed former Nashville Mayor Samuel Van Dyke Stout cut the rope; perhaps Stout was the “friend” to which Buntline referred.)

A few days later, after order had been restored, the grand jury absolved Buntline from any legal wrongdoing. He left town and apparently never stepped foot in Nashville again. However, the troubles of the widow Porterfield continued; the next year, after a lengthy and well-publicized public hearing, she was excommunicated from the Baptist church.

Incredibly, Ned Buntline’s Nashville adventure fits in with the rest of his life. After escaping death, he moved to New York and began writing popular fiction, most notably a series of stories that dramatized the squalid living conditions of the working-class people of New York (a prelude to the books of Upton Sinclair three quarters of a century later). He also started his own muckraking newspaper, Ned Buntline’s Own, and used it to publish his own stories and advance his causes, which by now included prohibition, suspicion of foreigners and Catholics, and reform politics.

In 1854 Buntline was credited (at least in one newspaper) with starting the political party now known as the Know-Nothing Party. “The Know-Nothing Party, it is pretty generally known, was first formed by a person of some notoriety who called himself ‘Ned Buntline,’” The New York Daily Times reported. “Ned instructed his proselytes and acolytes to reply to all questions in respect to the movements of the new party, ‘I don’t know.’ So they were at first called ‘Don’t-Knows,’ and then ‘Know-Nothings’ by outsiders, who knew nothing more of them than that they invariably replied ‘I don’t know’ to all questions.” The Know-Nothing Party was a notable factor in American politics but largely dissolved in 1856.

As busy and prominent as he was, however, Buntline was never out of trouble for long. With each expose and crusade, he took on new enemies. He was twice convicted for starting riots — first in New York and later in St. Louis. In 1854 he shot an African-American man, but he was later acquitted of murder on grounds of self-defense. And as far as his being a leader in the temperance movement, he might make a speech or two, “but only after he’d braced himself with a few drinks,” one account of his life claims.

Buntline was a soldier in the U.S. Army in the Civil War, enlisting as a private with the New York militia. It was, curiously enough, the most uneventful part of his life; he spent a year in northern Virginia, saw little combat and was discharged because of injury. (None of this stopped him from lying about his military career; he was often referred to as “Col. Judson” in later years.)

After the war, Buntline wrote dime-store novels with names such as “The Comanche’s Dream” and “The King of the Border Men.” Here he found his literary niche. Buntline wrote more than 400 novels, scribbling chapters on trains, in hotel rooms and whenever he needed the money and could find the time. During the years following the Civil War, he might have been the highest paid writer in America. Many people first learned about the American West by reading Buntline’s novels, which were inspired by real life events but not accurate depictions of the West.

In 1869 on a trip through the West, Buntline met Bill Cody, a trapper, former Pony Express rider and scout. Many of Cody’s friends were already beginning to call him “Buffalo Bill,” but it was a story written by Buntline in the New York Weekly that made Cody’s nickname a household phrase.

A few years later Buntline wrote a stage production called “The Scouts of the Plains,” featuring himself, Cody and “Texas Jack” Omohundro, another scout and hero of the Old West. Critics howled, but the public loved it, and the play launched Cody’s stage career (not Buntline’s because Ned was an abominably bad actor with a bad back, injured all those years earlier while trying to escape the Nashville lynch mob). In 1887 “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show” hit the stage, starring real cowboys and real Native Americans but not Ned Buntline. The show spent 10 of its 30 years in Europe and turned Buffalo Bill Cody into one of the most famous men in the world.

Buntline eventually returned to New York and remained a celebrity in his later years, frequently granting interviews. However, he was rarely asked about his near-brush with the Nashville lynch mob. When he died in 1886, practically every newspaper in America contained a lengthy obituary of the man, some of them replete with exaggerations and tall tales. “Ned Buntline probably carried more wounds in his body than any living American,” claimed one version of his obituary, which was published in dozens of papers. “He had in his right knee a bullet received in Virginia and had twelve other wounds inflicted by sword, shell and gun, seven of which were got in battle.”

Another claim: “He once earned $12,500 in six weeks, and at another time, under pressure, wrote a book of 610 pages in sixty-two hours, scarcely sleeping or eating during that time.”

Hundreds attended the funeral of Edward Zane Carroll Judson, aka Ned Buntline. A few days later, two women came forward, each claiming to be his wife and entitled to his estate.