Bugs (insects, to be more scientifically correct) are often considered foes in the garden and landscape. To Doug Tallamy, however, they are gifts to our ecosystems.

Tallamy, an entomologist — he’s a professor and chairman of the University of Delaware’s Entomology and Wildlife Ecology department — has demonstrated through his research and experience in his own backyard that nurturing the right insects is a good thing for plants and the environment.

His research on how plants and insects interact and the impact of non-native plants on insect populations was field-tested when he and his wife, Cindy, bought land in Pennsylvania in 2000. The two spent several years eliminating invasive and non-native plants from their property and replacing those alien plants with native species. Then they recorded the changes in the insect and animal populations that visited there.

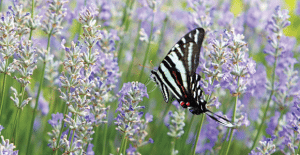

Today, their land is a haven for butterflies, bees, beetles and other insects that attract birds, reptiles, amphibians and many other species, some of which are facing declining populations and possible extinction.

As Tallamy began sharing the story of his research and personal experience with community groups, audience members often asked for “how-to” information, so he decided to write a pamphlet, which quickly became a book titled “Bringing Nature Home: How Native plants Sustain Wildlife in Our Gardens” (Timber Press).

To Tallamy’s surprise, this handbook that encourages replacing non-native plants with native species has caught on among garden groups and individual gardeners, even those who have traditionally promoted the use of non-native plants.

“The purpose of my book is to explain why your garden has an important ecological function today that it didn’t used to have,” he said: restoring biodiversity to our world.

According to Tallamy, biodiversity is in serious decline for a variety of reasons, including urbanization and the loss of natural habitats. As a result, whatever green space is left needs to nurture a diverse array of organisms, from fungi and bacteria in the soil to plants, insects and birds. Beyond supporting a healthy ecosystem, such diversity is critical to humans, who — whether they realize it or not — depend on biodiversity for their own survival.

Tallamy notes that one-third of North America’s birds are endangered or threatened and 33,000 North American wildlife species are imperiled. As he explains, these and other species help support a balanced ecosystem that provides the oxygen, water and other essential components of life that humans rely upon. Loss of any species, no matter how inconsequential it may seem, has a direct and potentially devastating impact on human lives.

Unfortunately, the way many people garden today does not promote a hospitable environment for diverse species. “People don’t realize that the way we have simplified our landscapes has played a big role in the loss of biodiversity,” Tallamy says.

Too often, landscapes are designed with just a few species of alien ornamentals, which, over time, become invasive and overtake native plants in the ecosystem. Tallamy’s studies have shown that insects often do not feed on those alien plants. Consequently, there are fewer insects to feed birds and other animals. Eventually, the displacement of native plant species leads to the disappearance of insect and animal populations.

But Tallamy believes that those very gardens can be transformed to support biodiversity without giving up the aesthetics of a beautiful landscape or without going completely native. “Increasing the percentage of natives in your garden is a good goal to start with and should generate feelings of accomplishment rather than guilt,” said Tallamy.

“Every time we use an alien plant when we could have used a native, biodiversity is lost. It is up to the individual gardener to decide how to deal with this trade-off,” he said. “I always say the more native plants the better, and as you increase the percentage of natives in your yard, you are providing more food and raising the carrying capacity of your yard. That does not mean you can’t use some non-natives, though.”

“The biggest bang for the buck is from woody plants because they generally support more biodiversity than herbaceous perennials and annuals,” he continued. And he suggests planting a variety of native plants as well. One way to approach this is to find and remove the highly invasive non-natives in your yard and have a plan for what natives will be put in their place. Another option is non-native attrition. Every time something non-native dies, replace it with something native and gradually increase the number of native plants over time.

Tallamy notes that even a tiny spot of land has an impact. “Don’t give up on small spaces,” he says. That small spot of biodiversity will draw beneficial insects and the birds, and by encouraging neighbors to do the same, the biodiversity of an area can expand, even in urban environments.

Another paradigm shift for many gardeners is to learn to love insects and accept them as an essential part of the ecosystem. Plant a garden not only for the beauty of the plants but also the beauty of the things that come to those plants, Tallamy says. “We have good data to prove that if you plant a diversity of native plants in the yard, they will attract a diversity of natural herbivores that, in turn, attract a diversity of natural enemies, which keep them in check,” he said. “You won’t have more insect damage if you plant natives.”

“Many of the insects you see are good guys, not bad guys,” he continues. “They will keep garden pests in check and create an ecological balance in your yard that will be interesting to watch but will not cause unsightly damage.”

“The central message I am trying to promote is that plants are more than ornaments,” he says. “They are the base of all the food webs on this planet, so if we only treat plants as ornaments in our landscape, we are losing one of their primary functions. That is dangerous for us. If we mess with the food web, we are messing with everything it supports and the biodiversity that produces the ecosystem