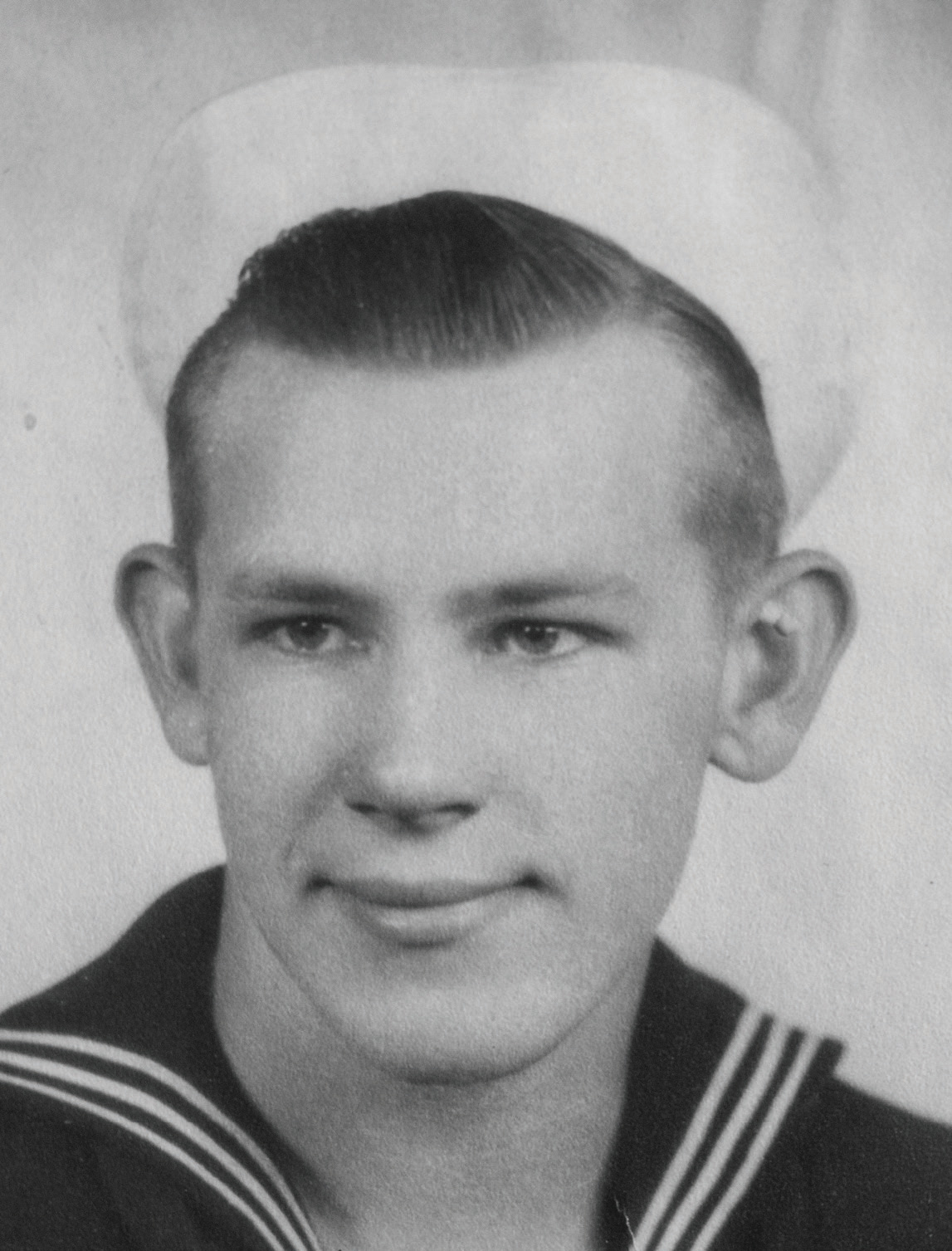

Bill Allen of Murfreesboro was there on the beaches of Normandy 76 years ago when a generation was called to fight the spread of tyranny and fascism. He recalls D-Day, what it meant at the time and what it means today.

On May 18, 1943, Bill Allen celebrated his 18th birthday and his graduation from Murfreesboro Central High School. Allen, now 95, could not have guessed that in little more than a year, he would be a survivor of one of the most daring, celebrated and deadly invasions in modern history: D-Day. Bill returned home to lead a life that “has been better than good,” he said, ever since he met his wife, Idalee, in 1955. Still, seven decades have not dimmed the veteran’s memories of World War II. Allen shares his remarkable story with great detail, wit and the perspective that comes from extraordinary experience.

“We were in the war the whole time I was in high school,” said Allen. The teenager knew he would have to do his part. “When you turned 18, you left. It didn’t matter how far along in school you were or anything. But since my birthday was in May, I knew I had a chance to stay and finish school. I played basketball, but we did not have a team my senior year; we discontinued everything due to the war. I lost my senior year. That hurt me very much… but I’ve learned since, there are things a lot worse than that.”

A group of Landing Craft Infantry sails toward Normandy via the English Channel on D-Day, June 6, 1944. The ship to which Bill Allen was assigned made the trip across the channel multiple times throughout the Invasion of Normandy.

Bill admits that when he joined the Navy, he “didn’t know a Band Aid from an aspirin tablet!” Still, he was made hospital apprentice and trained for months. “We were the medical part of the Navy. We maintained the healthy status of the ship; we operated sick bays, dispensaries, anything pertaining to health was within our jurisdiction.” The new servicemen were placed on a new ship — the LST-523. “We were the original crew on it,” said Bill. “We went out in March 1944.”

Having led a landlocked life until he joined the Navy, Bill didn’t know what to expect from a life at sea; he suffered debilitating seasickness for the four weeks it took to cross the Atlantic. Once in England, he began preparing in earnest for war. “We left the ship and went to chemical warfare school for two weeks,” said the veteran. “Just the medical personnel. Back on ship, we spent our time making bandages and dressings and sterilizing all our instruments. Meantime, we were in and out of different ports, loading to go out to the channel, turning around to come back, unload: practicing. One day we loaded up and didn’t go out in the channel, but we took off in the dark … we weren’t told anything, but we knew pretty well where we were headed.

A U.S. Navy LST similar to the one on which Bill Allen served sinks down by the stern off the Normandy beaches, the victim of a German attack on June 15, 1944. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives.

“We got into D-Day then.”

Codenamed Operation Overlord, D-Day began on June 6, 1944, when Allied forces landed along a 50-mile stretch of the coast of France. The term “D-Day” is a military term used to mark the beginning of any water-to-land operation, although there is some discrepancy on exactly what that “D” stands for. The U.S. Army has offered that D simply indicates the calendar day that an operation begins, just as H stands for the hour an operation is set to begin. In 1964, Dwight D. Eisenhower said any amphibious operation has a “departed date,” for which D-Day is a shortened version.

“Omaha” also was a code name. “Omaha Beach” refers to an area about 5 miles long, one of five sectors to be invaded by the Allied forces against the Nazis who occupied Normandy. Taking Omaha was the responsibility of the U.S. Army, Navy and Coast Guard plus British, Canadian and Free French navies. Bill’s ship, the LST-523, was headed there. Landing Ship, Tank (LST) is the Navy’s name for ships that carried tanks, vehicles, cargo and troops directly onto shore. Essential to beach invasions, the bow of an LST had a flat keel, allowing the ship to be beached upright, plus a large door that opened to a ramp for unloading.

Despite extensive preparation by the Allies, little went according to plan during the first days of the invasion, particularly on Omaha Beach. Navigation difficulties caused the majority of landing craft to miss their targets throughout the day. Allied planes that dropped 13,000 bombs before the landing completely missed their targets; naval bombardments alone couldn’t overpower German emplacements. Hospital Apprentice Allen stood helpless, on board, watching soldiers drown as they struggled to wade to shore; many who made dry land were killed or wounded almost immediately. As soon as his ship unloaded its mechanical and human cargo, Bill and his fellow medics began loading in casualties. Allen found himself reassigned to “death detail.”

Troops in an LCVP (Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel) approach Omaha Beach on D-Day, June 6, 1944. Imagine the thoughts of these soldiers as they approached the beach while German artillery ripped through Allied forces. The National D-Day Memorial Foundation cites 4,415 Allied soldier, sailor, airman and coast guard deaths on this one fateful day of the Battle of Normandy — a battle that helped pry Western Europe from the grip of Nazi Germany and paved the way for the end of the war less than a year later.

In the days that followed, LST-523 made three trips back and forth across the English Channel, retrieving casualties and delivering them to be cared for in England. Then, not quite two weeks into the battle, the worst storm to hit Normandy in 40 years began. The violent weather system did not abate until June 22.

On the afternoon of Monday, June 19, as the storm began, LST-523 was attempting its fourth landing at Omaha Beach when it hit a submerged German mine. The impact of the explosion split the ship in two, causing it to sink rapidly. Minutes before the explosion, Bill and a couple of soldiers had decided to sit inside a jeep that would have been unloaded had the doomed ship landed. The vehicle sheltered the servicemen from the initial rain of debris that mortally wounded or killed many on board. Most of those left alive on the ship were swept off deck and into the channel. Bill scrambled out of the jeep un-harmed but then realized that, perched on the bow of a sinking ship, he could not survive in the water.

The harrowing story Bill tells of his rescue from the dying ship to a life raft, his own efforts to successfully rescue four more servicemen and their subsequent journey to safety embodies the very essence of war: fear pitted against courage, daring risks in the face of dangerous odds, life snatched from a literal sea of death, and faith rediscovered after hope had been abandoned.

Bill and his wife, Idalee, look over his mementos, letters and medals from his military service. Bill and Idalee met and married after Bill’s return from World War II, and it was many years before she knew the extent of what Bill went through on D-Day. They have been married for 64 years and have two daughters, four grandchildren and five great-grandchildren (with a sixth due in December).

Out of 145 Navy personnel on board, only 28 survived. Bill and other survivors were transported to England, where they recovered, assuming that soon they would be sent to the next desperate war zone: the South Pacific. In the meantime, they were granted a 30-day leave.

“We were tickled to death to get 30 days leave, and we headed home — me and Ed Phillips, himself,” said Bill. “We pulled into Murfreesboro. It was just about dark, 8:00 or so, I guess. I went to call my parents … they didn’t know anything. They knew my ship had been lost and that I was missing in action. All our correspondence had stopped. So they were living in just total suspense. Mother answered the phone. I said, ‘Mother!’ She said, ‘Where are you?’ ‘I’m at the bus station here in Murfreesboro.’ I heard a thump, then, ‘Bill!’ and it wasn’t two or three minutes until I hear hollering, horns blowing, tires squealing, dog barking — we had a reunion right there in the middle of the street!”

Bill Allen holds a particularly meaningful memento labeled “Sand, Omaha Beach, Normandy, France.”

“Every boy and girl should have to know some of the price that’s been paid. Think of the mothers, the tears they have shed over their sons…Husbands who left, never to come back. Children who never had an opportunity to see their fathers.”

The two sailors had to return to base after leave, thinking they were going to be shipped out, but “a doctor blocked me from going,” said the veteran. The military physician responsible for examining them before their next assignment knew what Bill and his fellow Navy men had endured and prevented them serving in any further combat conditions. Navy Hospital Apprentice First Class Allen would spend the remainder of his service on land, far away from battle.

Bill returned to Murfreesboro and decided to “get to work and get on with my life.” He played baseball and kept stats for other teams when games were being aired on radio. Bill married, and he and wife Idalee had two daughters. He worked for the Murfreesboro Electric Department for 32 years. It was about 25 years before he began to openly recount stories of his service with other veterans, and Idalee was astonished to hear what her husband had lived through. Eventually, veterans of World War II began to age, and D-Day celebrations became more prominent. Bill started getting requests to speak about what he experienced when he answered his country’s call to serve.

“Freedom is the highest-priced thing this nation has ever bought.”

One afternoon in August 2013, Bill answered another call — a ringing phone — and on the other end was Doug Hamilton with the Public Broadcasting Service. Ultimately, Bill’s family was treated to a trip of a lifetime, along with other battle survivors, back to the site of the Normandy Invasion. A subsequent documentary aired on PBS in June 2014 to commemorate the invasion’s 70th anniversary. The trip offered several opportunities for Bill, including the chance to take a small submarine down to the bottom of the English Channel near Omaha Beach to see the remains of his lost ship. “I could see the number on the side of the ship, the 523, algae and seaweed and all that grown over it,” said Bill. “I saw enough that I was convinced it was the ship I was on.”

“We went up on top of the cliff to the American cemetery (for the main event of the anniversary special),” said Bill. “Over 9,300 and something buried there in that cemetery. One of my doctors was buried there. I believe it’s the most sacred place I’ve ever been. I’ve been in a lot of churches, but I’ve never been in a church more sacred than that was. We spent all afternoon there in that cemetery, looking at other graves. People found out we were there; they got to coming up, speaking, thanking me — even the little children. They kept the cemetery open 30 extra minutes for people to speak to me.”

Bill said that in recent years, he wrote his story for his children and grandchildren. “I told them that I hoped and prayed that they’d never have to experience war … but if they did, be willing to do your part, because you live in the greatest country in the world,” he said. “It has to be defended, and don’t be ashamed to stand up and defend this country. I have for a long time been a strong believer that every boy and girl should have to know some of the price that’s been paid. Think of the mothers, the tears they have shed over their sons. Wives whose husbands left, never to come back. Children who never had an opportunity to see their fathers.

“Freedom is the highest-priced thing this nation has ever bought.”

More online

Visit tnmagazine.org for more, including a video interview with Bill Allen.

Cindy Kent is author of “Better Men: Alpha Upsilon in Vietnam,” a compilation of the stories of 14 fraternity brothers from the University of Tennessee at Martin who went to war between 1964 and 1972.