A few weeks ago, I saw something in the hall of my son’s school in Williamson County that astonished me.

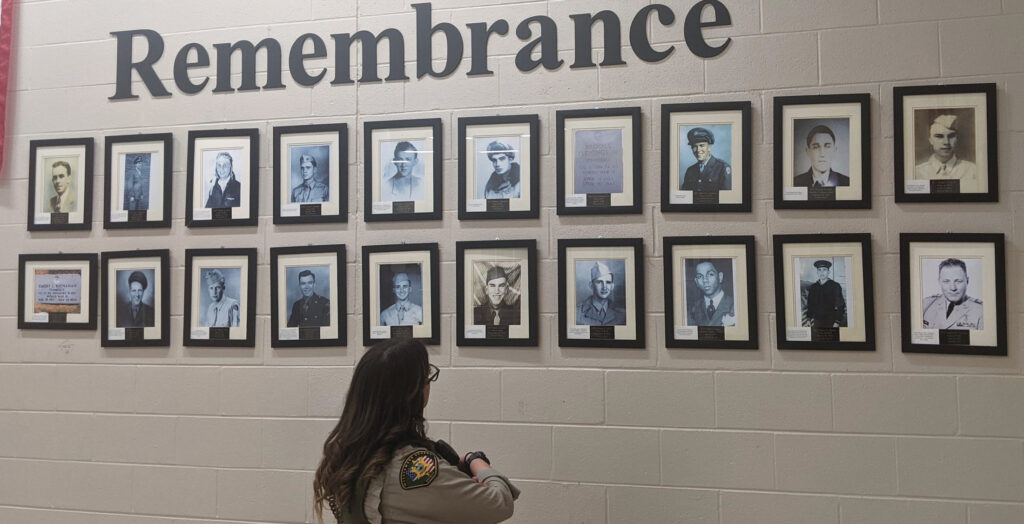

Franklin High School has a Wall of Remembrance honoring its alumni who died in military service — along with those of the all-black institutions known as Franklin Training School and Natchez High School, which predated integration.

There are frames representing 33 men on the wall. They include people who died in World War II, Korea, Vietnam, the Cold War and Iraq. There are photos of 32 of the 33, with brief descriptions of what they did in the military.

As a veteran, I’m overwhelmed by this Wall of Remembrance and the work that went into it. I’ve spoken to Lt. Col. William Hoover, who put it up when he was head of the JROTC program there, and I visited the Williamson County Archives, whose staff helped him do most of the research behind it. I’d love to see other high schools do something similar. (And if there is another high school that honors all its graduates who died in military service in this manner, please email me at [email protected], and I’ll mention it in a future column.)

First, let me mention some of the stories of the people honored on Franklin High’s wall, with tidbits I’ve found in their obituaries:

Stories of the dead

There are a lot of lessons on the Franklin High School Wall of Remembrance.

The earliest graduate on the wall is Capt. Silas Carlisle of the Class of 1932; the most recent is Petty Officer 2nd Class Matthew Bergman of the Class of 2008.

If you peruse the wall, you will notice that 13 alumni of Franklin High died in military service in 1944. The next highest year represented on the wall is 1966, when four alumni of Franklin High and Natchez High died in Vietnam.

Four of the 33 men on the wall were officers; 29 were enlisted men. The highest-ranking was Maj. James Conway, a special forces officer declared missing in action in April 1966.

Some of the stories on the wall remind us that many families had to wait a long time to learn the fates of their loved ones. Sgt. Mack Terry (Class of 1939) died at a Japanese prisoner of war camp. From my research, I learned that his family was notified that he was missing in August 1942; they were told that he had been taken prisoner in April 1943; they were notified that he had died in July 1943.

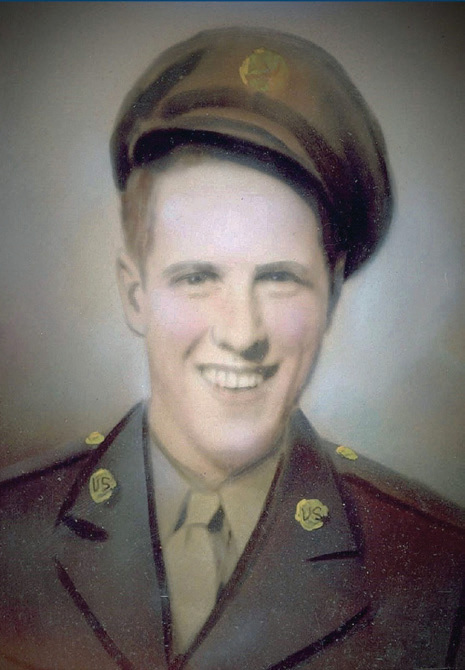

Reedy Sears graduated from Franklin High in 1939. His name appeared regularly in the Clarksville newspaper in the early 1940s, when he played football and basketball at Austin Peay. Sgt. Sears was a radio operator and gunner on a B-17 that was shot down over Germany in November 1944. He was declared missing at that time and declared dead a few months later.

Franklin High alum Petty Officer 2nd Class James Harper was one of about 800 crew members who perished when his aircraft carrier was bombed by the Japanese in March 1945. The name of his ship was the USS Franklin.

“He was determined to get into the Navy,” Harper’s mother said after he died. “He had a mind and a will of his own, that boy.”

It is striking how young the Franklin/Natchez High alumni who died in the Vietnam War were. Among the Vietnam dead were Spc. John Woods (age 19), Pvt. Charles Hardison (19), Cpl. Larry Buford (20), Pfc. Richard Carothers (21), Pfc. Danny Marlin (21), Pfc. James Cunningham (22) and Spc. James Peay (22).

Speaking of Vietnam, it is notable that Tennessee’s public school system was segregated during that war, but the U.S. military was not. Four of the nine Vietnam War deaths on the wall went to Natchez High, five to Franklin High.

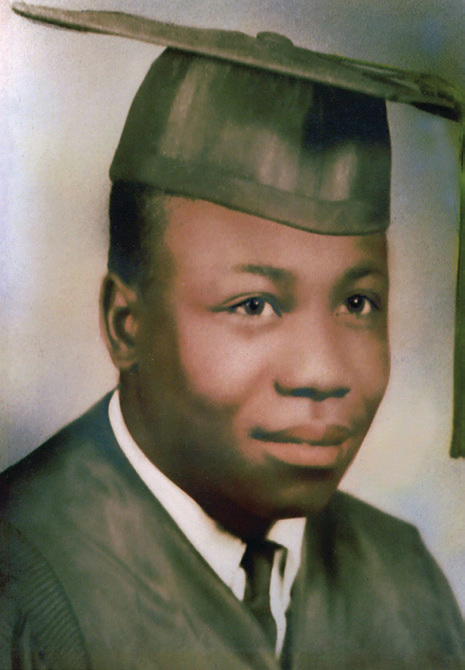

Pvt. James Cunningham (Natchez Class of 1964) died in Vietnam while treating the wounds of his commander, who was almost certainly white. “After learning that his company commander had been wounded, and although enemy mortar rounds were raining upon the area, PFC Cunningham hurried to the aid of his leader,” said Cunningham’s Bronze Star certificate, which his family received posthumously. “As he was treating the wound, a hostile mortar round exploded nearby, fatally wounding him.”

Cunningham was not allowed to attend school with white people, but he likely died trying to help a white person.

Story behind the wall

Hoover created Franklin High’s Wall of Remembrance about 15 years ago as part of the school’s centennial. “We had a night where we recognized all living Franklin graduates who were veterans, and they ranged from young to very old,” he says.

Hoover then visited the Williamson County Archives and found that — thanks largely to longtime County Archivist Louise Lynch — it had enormous amounts of information to offer him. “Given the time involved and the research I had to do, I could not have found all these photos without the archives,” says Hoover.

Franklin Principal Willie Dickerson, a Natchez High graduate, directed Hoover to put the Wall of Remembrance in the hallway across from the concession stand that is used during basketball and volleyball games. “We obviously wanted the students to see it,” Hoover says, “but we knew that if we put it there that people who visit the school would be more likely to see it as well.”

It took Hoover several months to put it all together, and it was dedicated in November 2012. “There were family members who came to the ceremony,” Hoover recalls. “There were parents who came, widows who came, children of veterans who came. It was really special.”

Hoover admits that it is possible that there are names missing from the list. “If we ever found anyone we overlooked, I would assume that this person would be added,” he says, pointing out that he is retired from Franklin High School and its JROTC program.

How to do something similar

It would be refreshing to see other schools put together Walls of Remembrance similar to Franklin High’s. Researching the wall would be a great project for a high school history class.

Here are a few tips:

The most obvious way to start a Wall of Remembrance is by word of mouth. If teachers advertise in local newspapers and social media that they are creating a list of graduates who died in military service, they might be surprised at how fast they can put together a list. Then, using research tools such as newspapers.com, it might be possible to track down obituaries, which would confirm the circumstances of their deaths.

I strongly endorse the use of county archives. Your archives might already have a record of known local veterans who died in military service, similar to the one in Williamson County. “We have two file cabinets with folders on many veterans from this county,” says current archivist Bradley Boshers. “Some of these files contain government records, some newspaper articles and some photos.”

Leesa Harmon, a public archivist for the Williamson County Archives, says she has had a lot of success with two websites. “I’m amazed at what I’ve been able to find on Fold3.com (a paid site) and teva.contentdm.oclc.org (a free site produced by the Tennessee State Library and Archives),” she says. “I’ve had a lot of success tracking down records and photos, especially of World War I veterans.”

Finally, a word about population patterns: If you write a list of current high schools in Tennessee and compare it to a 1945 list, you will notice that there is little overlap. There are a number of reasons for this phenomenon: Schools consolidated; districts shifted; buildings were torn down and rebuilt in another location with a new name; interstates were built; apparel factories closed; car parts factories opened; new neighborhoods were developed; etc.

Let’s also not forget that every black Tennessean who died in World War I, World War II, Korea and Vietnam went to an all-black high school. (I did a whole column about these institutions in February 2020 and tried to compile a complete list of them at that time.) These high schools are all gone, although some of the buildings are still in operation as integrated institutions.

My suggestion to a teacher wanting to do a Wall of Remembrance is to study the district covered by your current school and find out what school served that district in the early 1900s. Your wall might, like Franklin High’s, include names from more than one school.

I can assure you, however, that a photo of a person who went to school in that same part of the county — and who then went on to die in World War II or Vietnam — will mean a lot to a young person today.