It was the South’s most desperate battle — and is the South’s least-remembered.

In December 1864, what was left of the Confederate Army of Tennessee fought for two days in an attempt to wrest control of Nashville from the Union Army, which had held the city for the previous two and a half years. Outnumbered three to one, the Confederates fought bravely but were routed and chased south for the last time.

At Shiloh, Stones River and Fort Donelson, large parts of the battlefield are preserved in national military parks with visitors’ centers and full-time staffs. Even in Franklin, where there is no national military park, about 175 acres of the battlefield are preserved, and there are two structures — the Carnton Plantation and Carter House — whose stories are linked with the battle.

The battlefield of Nashville, however, is now nearly covered by houses, churches, businesses and roads. Many people who died were buried in unknown places throughout the Green Hills and Oak Hill parts of town. Visitors can inspect the remains of a Civil War fort (Negley), but it wasn’t the scene of the major part of the battle.

It is only through the recent efforts of a few local history buffs who formed the Battle of Nashville Preservation Society that many of the remaining battle sites have even been found.

This amazing photo taken from Fort Negley shows the inner line of Union Army defenses at the Battle of Nashville (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Civil War Photographs, LC-DIG-cwpb-02089).

Here is some background on the Battle of Nashville:

In the fall of 1864, Confederate Gen. John Bell Hood left southern Georgia undefended and marched his army back to Tennessee. On Nov. 30, 1864, his army lost about 7,000 of its 20,000 fighting men in a disastrous assault at the Battle of Franklin.

After Franklin, Union Gen. John Schofield (a West Point classmate of Hood’s) ordered his men to go back to the fortifications protecting Nashville. There the Union Army could rest, be fed and stay protected by two different networks of entrenchments — an inner line that was seven miles long and outer one that stretched 13 miles. The inner line of defenses included several forts, the largest of which was Fort Negley.

In spite of his defeat at Franklin, Hood ordered his soldiers to continue north to the outskirts of Nashville. For about two weeks, the Confederate troops lived in makeshift entrenchments. By this time, most of them were exhausted and suffering from malnutrition. Many of them didn’t even have shoes!

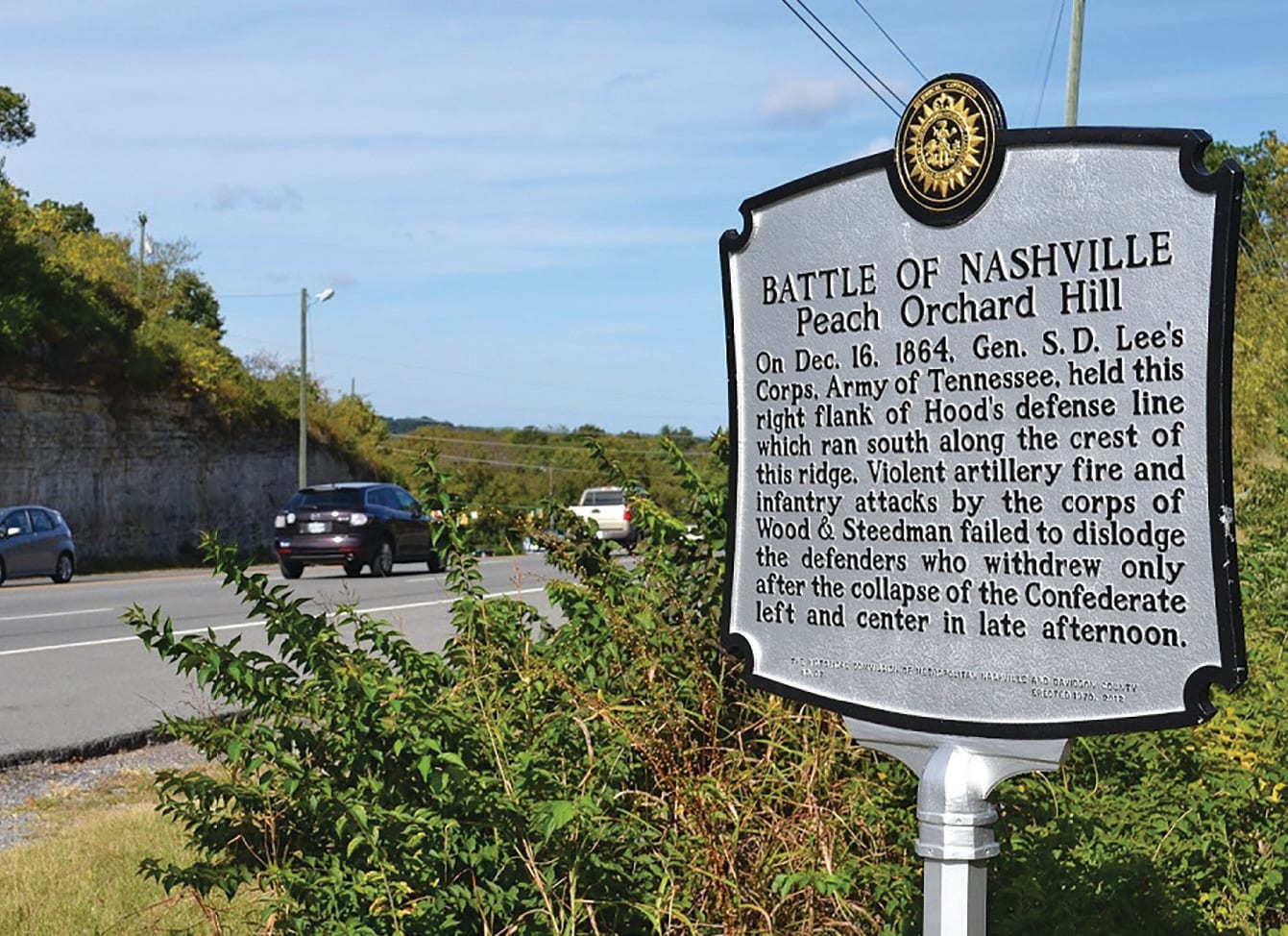

The peach orchard, where so many African-American soldiers died during the Battle of Nashville, has long since been developed (Tennessee History for Kids photo).

In Nashville, the Union Army was under the command of Gen. George Thomas (who was senior to Schofield). For the first two weeks of December, President Abraham Lincoln was displeased that Thomas allowed the Confederate Army time to rest and dig fortifications.

However, Thomas knew something Lincoln didn’t: The weather in Nashville was terrible! Not only was it hard to imagine moving an army in the middle of snowy and icy weather, but Thomas knew that the elements were much harder for the Confederates to bear than his Union troops, who had better guns, more food, plenty of clothing and better shelter.

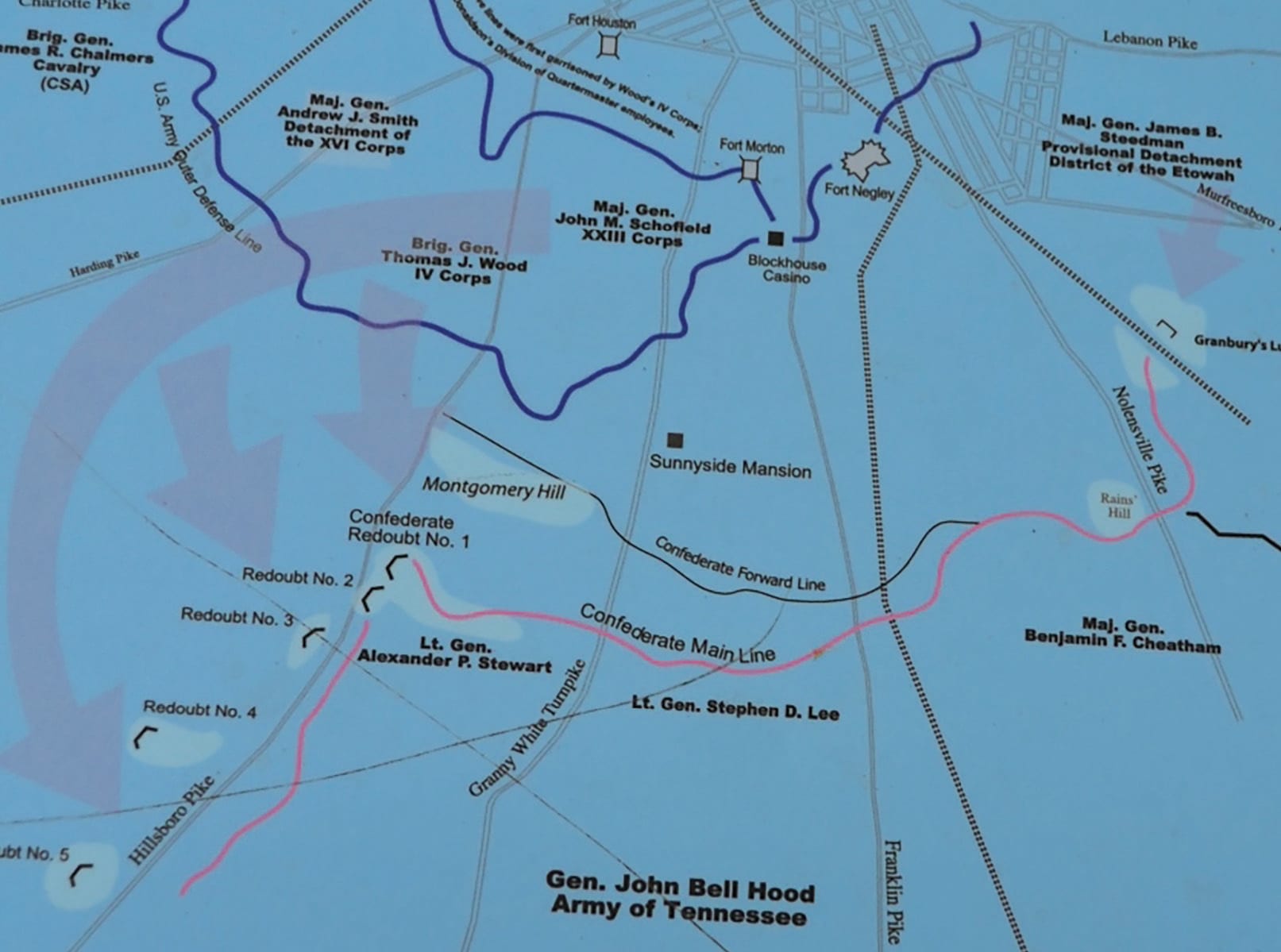

Finally, on Dec. 15, Thomas ordered his army to attack. At 8 a.m., on the Union left (the Confederate right), a Union force attacked a Confederate dirt fort called Granbury’s Lunette near the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad.

The Confederate troops won this initial skirmish. However, Gen. Hood didn’t realize that the attack on the Lunette was a diversionary tactic meant to hide the fact that the primary Union attack was coming on the opposite end of the battlefield.

As part of this main attack, 8,000 Union cavalry and 37,000 infantry advanced west, then south, and attacked the small fortresses that the Confederate Army had built in the vicinity of Hillsboro Pike. (So, on this western end of the battlefield, about 6,000 Confederates were up against some 45,000 U.S. Army soldiers!)

Today it is very hard to imagine this Union assault. On the land over which the Union troops traveled is now houses, businesses, roads, Interstate 440 and the Vanderbilt University campus. Furthermore, the land is now covered with tens of thousands of trees.

However, at the time of the battle, practically none of this part of Davidson County had been developed. Photos from the time show that the Union Army had cut down every tree in the area.

For a while, Confederate soldiers managed to hold off the Union assault. Eventually, however, thousands of well-armed Union soldiers overwhelmed the Confederates, forcing them to fall back, surrender or fight to the death.

Darkness came early on Dec. 15, 1864. As they withdrew after the fighting on that day, the Confederates formed a relatively straight line starting at a place known as Compton’s Hill and going all the way east to a peach orchard that was part of the Travelers Rest estate. This Confederate line was located along what is now Harding Place/Battery Lane.

After the Confederates spent all night frantically creating defenses, fighting resumed the next day. Around 3 p.m., about 6,000 Union infantrymen attacked at the peach orchard.

“As they approached (the Confederate) line, they became entangled in fallen tree tops, laid out to slow them down,” Ross Massey writes in “Nashville Battlefield Guide.” “As they struggled to get through, Confederate artillery opened, and the infantry rose up and poured out a deadly fire. The attackers were confused and broke for the rear, ending their part in the battle.

“Local legend says it would have been possible to walk across the slope of the hill, stepping from one dead Yankee to another.”

Many of these Union soldiers were members of the 13th United States Colored Troops, which lost at least 220 officers and men at the peach orchard.

Things went better for the Union at the other end of the battlefield. Atop Compton’s Hill, about 1,500 Confederate soldiers tried to hold out against an armed force several times its size. They fought bravely, but eventually the musket and cannon fire took its toll, and Union soldiers (many of whom were from Minnesota) fought their way to the top.

The Confederate cause was lost for good when Col. William Shy was mortally wounded. At that time, Compton’s Hill became known as Shy’s Hill.

The Battle of Nashville monument is located in a park at Granny White Pike and Battlefield Drive.

After the defeat at Shy’s Hill, the entire Confederate line ran southward in retreat. “Such a scene I never saw,” wrote Sam Watkins, a private in the Army of Tennessee who was shot three times in the battle. “The army was panic-stricken. The woods were everywhere full of running soldiers. Our officers were crying, ‘Halt! Halt!’ and trying to rally and re-form their broken ranks.”

The Confederate Army of Tennessee didn’t stop marching until it got to Mississippi.

The Union Army later reported that 387 of its soldiers were killed and 2,500 wounded in the two-day battle. The Confederate Army was never organized enough to report its casualties after Nashville. But it is believed that about 4,500 Confederates were killed, wounded or captured at Tennessee’s most forgotten Civil War battle.

This map shows the lines on day two of the Battle of Nashville.