One hundred ten years ago, three companies battled Mother Nature and labor disputes to pioneer hydropower in the Tennessee Valley

First some background: The science behind hydroelectricity reached a fever pitch around the turn of the 19th century. Hydroelectric dams had been built before, most notably at Niagara Falls, and the technology had great promise. This led enterprising individuals to gaze longingly at the tributaries of the Tennessee River that descend from the Appalachian Mountains as potential sources of electricity.

The Chattanooga & Tennessee Power Company was the first to break ground on a hydroelectric dam in Tennessee — on Hales Bar, about 30 miles downstream from Chattanooga on the Tennessee River — in 1905.

Unfortunately, the Hales Bar project had all sorts of problems. The bedrock at the bottom of the Tennessee River was more porous than the engineers had hoped. “Although it was an easy matter to make the dam watertight, it was found that great quantities of water spurted up from fissures in the bedrock itself,” explained a trade publication. To make the barrier watertight, workers tried to plug the massive limestone tunnels using every means possible, a frustrating and dangerous battle with Mother Nature that took years.

In search of workers, the company brought in Italian and Hungarian immigrants from New York City. They were housed along with men from the region in a makeshift community known as Sucktown, named for one of the barriers to navigation to be overcome by the lake created by the dam.

Sucktown was a scary place. In 1907, there were at least two strikes — one of Italian workers and another of White workers who were angry that an African-American had been put in a position of authority. In February 1910, at least three Black men were killed in an incident dubbed a race riot by newspapers across the country.

Meanwhile, as if to confirm the notion that there was a curse on the project, laborers repeatedly unearthed skeletons while digging at Hales Bar. No one knew — or will ever know — if the bones were the remains of mound builders, Chickamaugan Indians, Civil War soldiers or none of the above. “Last week was not the first time human bones have been pitched out by the diggers,” the superintendent explained in May 1908. “If you go down there you will see that sort of thing happen most every day.”

Then there were issues between the power company and four general contractors. Details of why the first three contractors were fired filled a lot of newspaper articles, but suffice it to say that the dam and hydroelectric plant cost more than three times the original estimate.

The Hales Bar dam, plant and power lines were finished in the fall of 1913 — a season that proved to be, quite literally, a watershed moment for Chattanooga and the Tennessee River. Around Oct. 20, the dam was closed, and the waters upstream began to rise. Forever submerged beneath the waters of the manmade lake were all the legendary barriers to navigation that had played such an important role in the story of the Chickamaugan Indians, the saga of river commerce and tales from the Civil War. “Take a last look at the suck, the pot and the skillet,” the Chattanooga News said on Oct. 23. “They now pass into the history of impeded river transportation.”

It was a remarkable month for Chattanooga. What no one bothered to point out was that the Hales Bar Dam was the first to start construction in Tennessee but the third to be completed.

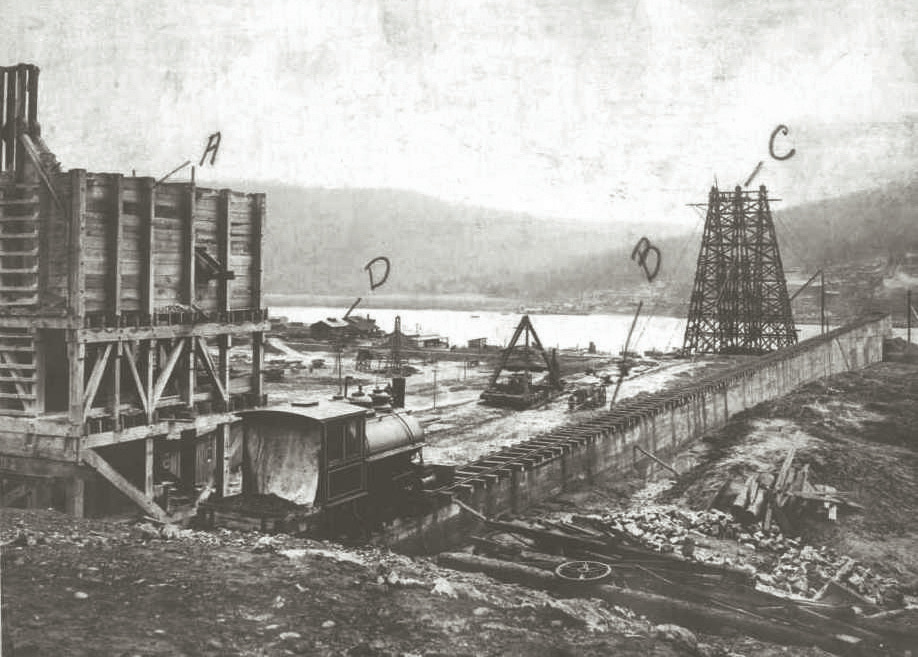

You see, in 1910, projects for two other hydroelectric dams were commenced in East Tennessee. Neither was nearly as large as Hales Bar. One was the Watauga Dam (now known as Wilbur Dam) in Carter County. This dam was financed by the Watauga Power Company and intended to provide power for the tri-cities. Its general contractor was W.J. Oliver, who was restoring his reputation after the bad publicity he received from being fired from the Hales Bar project.

Watauga Dam began producing electricity on Christmas Day 1911. “Ere long the wonderful waterpower of Tennessee, said to be perhaps greater than is afforded by any other state in the South, will be put to use for commercial and manufacturing purposes,” the Charlotte Observer pointed out.

A third firm called the East Tennessee Power Company finished a dam on the Ocoee River at Parksville about a month after Watauga Dam was finished. Its intention was to sell power to the copper factories on Polk County’s Ducktown Basin, but it also provided electricity to Chattanooga. “The current came singing into the station, the song proving to be delightful music in ears of electricians,” the Chattanooga Daily Times reported.

All this dam building was watched closely by big national companies, including a bustling Pittsburgh-based firm called Aluminum Corporation of America, later known as Alcoa (much more on this subject in a future column!).

I write all this because we normally associate the Tennessee Valley Authority with the development of hydroelectricity. But TVA came a generation after this first wave of dams. TVA acquired Watauga, Parksville, Hales Bar and other dams produced by these predecessor companies and went on to build much larger dams such as Norris, Nickajack and Pickwick Landing. It’s important that we remember the companies and workers who came before TVA.