In Tennessee, each town used to determine its own time

Exactly what time did the Battle of Shiloh begin? What was the time when the Tennessee Constitutional Convention of 1796 finished its work? Precisely when did Andrew Jackson leave the Hermitage to be inaugurated as president?

The answer to all these questions is we don’t know and will never know. You see, the idea of exact time evolved in Tennessee (and American) history. Today there are four time zones in the continental U.S., and everyone knows what time it is in each of them. But in the 19th century, every town had its own time based on when a local dignitary calculated that the sun passed overhead.

The answer to all these questions is we don’t know and will never know. You see, the idea of exact time evolved in Tennessee (and American) history. Today there are four time zones in the continental U.S., and everyone knows what time it is in each of them. But in the 19th century, every town had its own time based on when a local dignitary calculated that the sun passed overhead.

I’ve compared several newspaper references from the 19th century and have pieced together the following relationship: New York City time was 24 minutes ahead of Washington, D.C., time, which was 11 minutes ahead of Knoxville time, which was 20 minutes ahead of Nashville time, which was seven minutes ahead of Clarksville time, which was eight minutes ahead of Memphis time, which was 10 minutes ahead of New Orleans time.

You got that?

I’m staggered by the number of problems this would have caused. How did people schedule meetings? How many legal cases were affected by confusion as to the time of the crime?

And how did moving armies in the Civil War communicate battle plans and orders to each other since there was no time standard?

I’ve concluded that most towns had highly visible clocks displaying the official time and that people set their pocket watches based on that time. Towns that didn’t have big clocks had residents who complained about it. In 1859, the Memphis Appeal urged the city authorities to invest in a big clock. “For want of a true and universal standard of time, a thousand hours are lost in this city daily, by reason of people not being able to move and meet upon punctual time,” the paper said.

I would have thought that universal time was brought on by the advent of the telegraph, but, in fact, it was the railroads. Not long after the arrival of railroads onto the American scene, it became obvious that some standard time was necessary (there was a deadly train collision in Massachusetts caused by confusion as to the time).

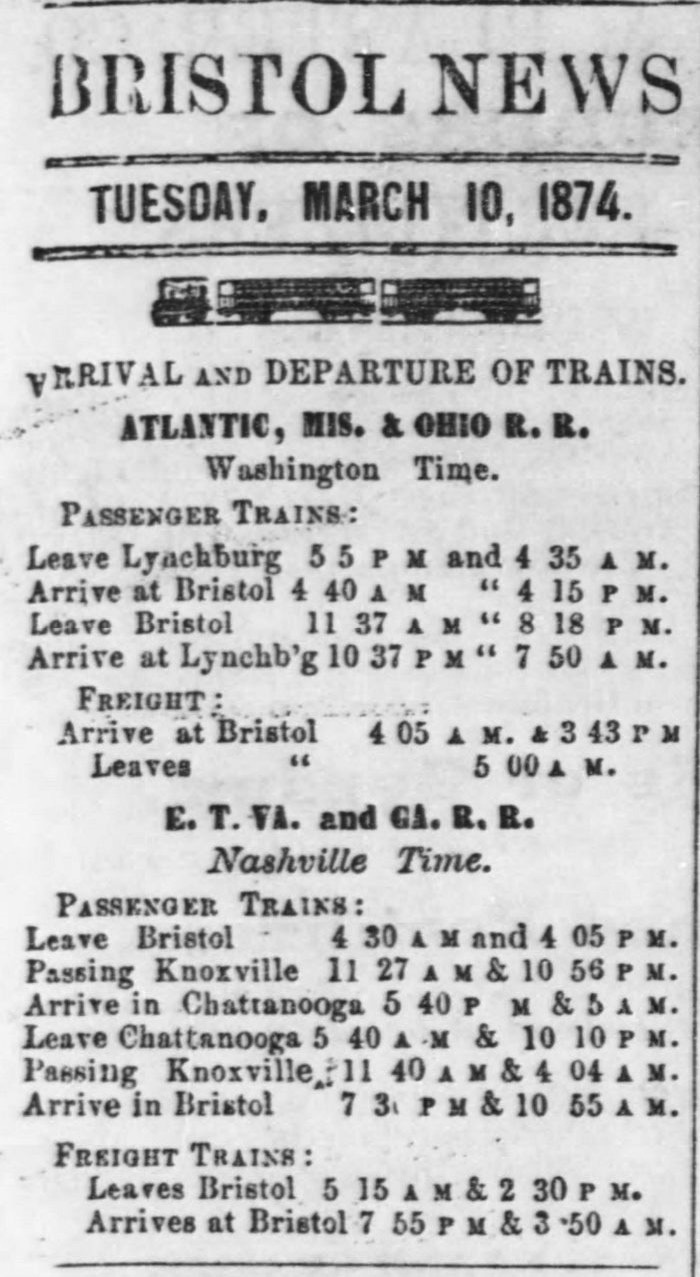

However, railroads were in competition with each other, so they didn’t exactly cooperate. Each railroad came up with its own time — that of a city in the region in which it operated. The Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad ran on Washington, D.C., time. The Louisville and Cincinnati Railroad ran on Lexington, Kentucky, time

In cities with multiple railroads, it must have been fun to keep up with the timetables. “Rail road time twenty minutes faster than city time,” advised an item for the Memphis and Charleston Railroad in the April 21, 1868, Memphis Public Ledger. One inch below, an item for the Memphis and Louisville Railroad stated that “railroad time is 15 minutes faster than city time.”

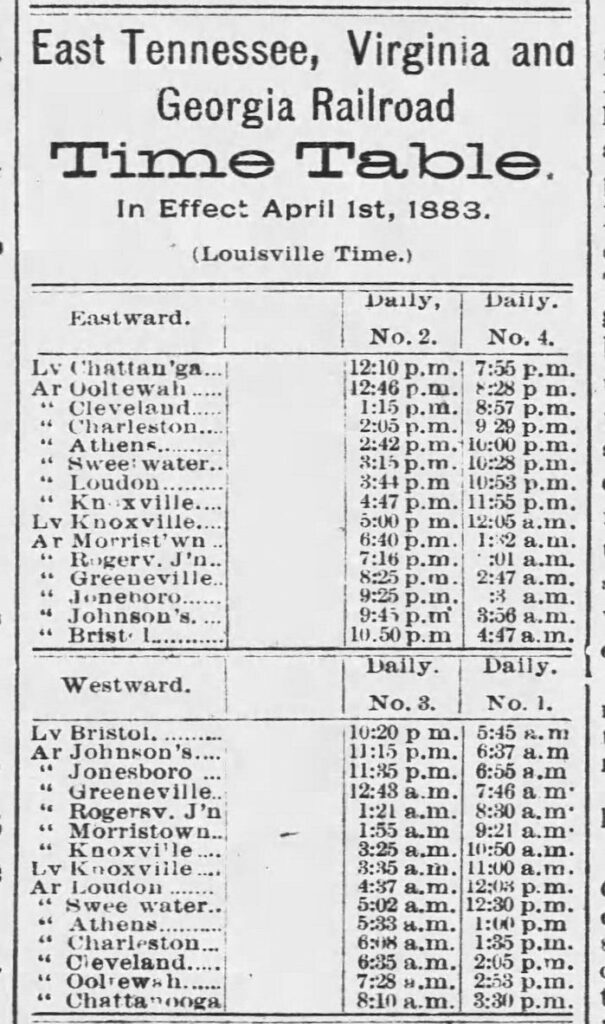

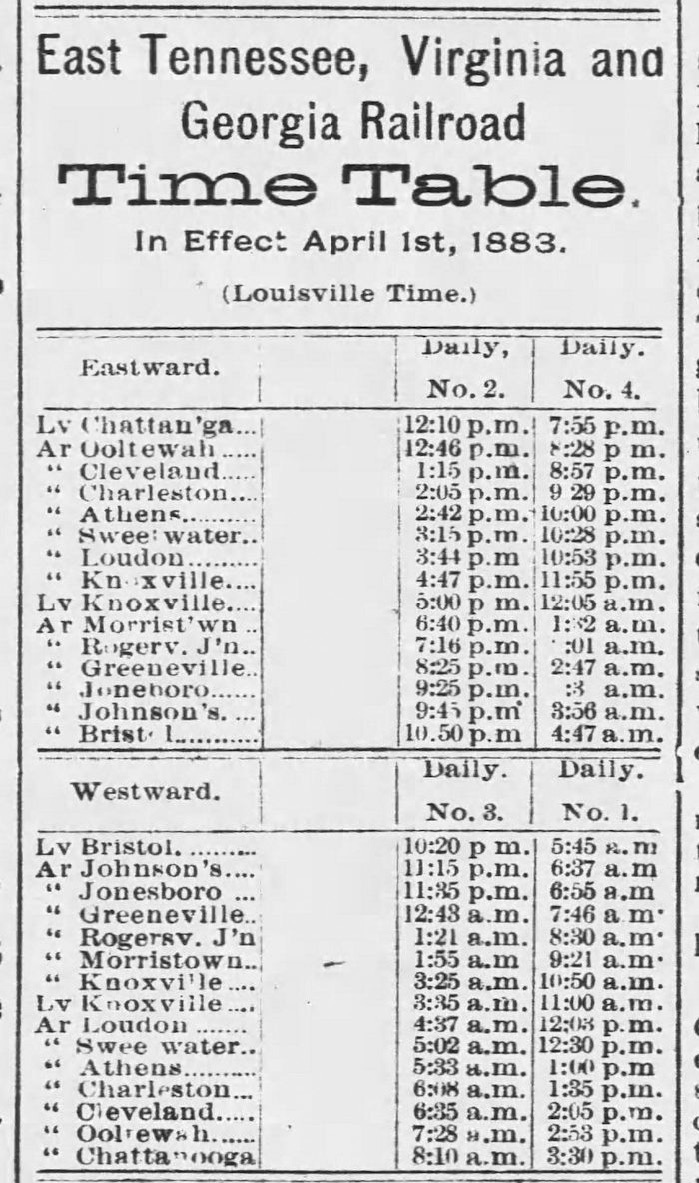

To add to the confusion, railroads sometimes changed the time zones they used. In 1874, the East Tennessee, Virginia and Georgia Railroad ran on Nashville time. Nine years later, the same railroad ran on Louisville, Kentucky, time.

Speaking of the East Tennessee, Virginia, and Georgia Railroad and time confusion: In July 1880, the Chattanooga Daily Times informed its readers that the railroad operated 12 minutes faster than Chattanooga time. Nine months later, the same newspaper contained an item that stated that the same railroad operated 15 minutes faster than Chattanooga time.

This chaos remained until 1883 when the railroads divided the country into four time zones and came up with a time known as “Railroad Standard Time.” The switch happened on Nov. 18, which must have been a strange day to ride a train. “Should any train or engine be caught between telegraph stations at 10 o’clock a.m. on Sunday, November the 18th, they will stop at precisely 10 o’clock, wherever they may be, and stand still and securely protect their trains or engines in the rear and front until 10:18 a.m.”

Shortly thereafter, most large cities officially shifted to Railroad Standard Time. For instance, Nashville shifted over to Railroad Standard Time a week later. “The town clocks will be set back to the standard time today,” the Nashville American reported on Nov. 25, 1883.

However, some towns and cities resented the idea of big business deciding what time it was, so they refused to adopt Railroad Standard Time for a while. Chattanooga was one such place, and its newspaper ridiculed the city for it. “Last week there was only 15 minutes difference between the standard railroad time and the city time,” reported the Chattanooga Times on Feb. 15, 1884. “This week the city time is fully 20 minutes faster than standard time.”

I don’t know when Chattanooga came around to Railroad Standard Time, but I do know that Detroit, Michigan, famously refused to switch away from local time until 1905.

If there were any holdout towns and cities remaining on local time in the United States, those vanished in 1918. In that year Congress enacted the Standard Time Act, making precise time an official and legal concept in the U.S.

Today, we have many things we can argue about. But at least we can agree on the time, right?