When it comes to history, politicians and generals get all the glory, but no one gives credit to the engineers.

Stephen Harriman Long and John Edgar Thomson are two examples. Were it not for Long, Chattanooga might not exist. On the other hand, Shelbyville might be a large city today had it not been for Thomson.

Here’s the background: Georgia was about 10 years ahead of Tennessee when it came to building railroads. By the mid-1830s, the Peach State had several railroads in the works with names such as the Central of Georgia Railroad, Monroe Railroad and Georgia Railroad. All three were intended to link the Atlantic Coast and Savannah River with points in the interior of that state.

Then, in 1836, the Georgia government started the Western and Atlantic Railroad. The idea of the W&A was to connect the interior of the state to the Tennessee River. The W&A hired Stephen Harriman Long — who had engineered large parts of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad — to be its lead surveyor.

Sometime in the late 1830s, a member of Long’s team drove a stake in the ground 7 miles east of the Chattahoochee River in Fulton County, Georgia. The town that grew up around “Zero Mile Post” was originally called Terminus.

Long and his colleagues then surveyed the best route to connect Terminus to the Tennessee River. They had two main choices. One was for the railroad to head west to Gunter’s Landing — a place in northeast Alabama where the Tennessee River turns from a southwest heading to a due west heading. The other was for the railroad to head northwest to Ross’s Landing — a place in southeast Tennessee where the river also turns from a southwest heading to a due west heading.

Long recommended Ross’s Landing. His report was published in the September 18, 1839, (Nashville) Republican Banner. It pointed out that:

- The Gunter’s Landing route would be about 45 miles longer than the Ross’s Landing route.

- The Gunter’s Landing route would have to pass over Alabama’s Sand Mountain, “which can only be crossed by means of three, perhaps four, inclined planes, at an ascent of more than 100 feet per mile.”

- Gunter’s Landing was more likely to flood than Ross’s Landing.

Officials also favored Ross’s Landing over Gunter’s Landing because of a belief that a private company would soon build another railroad heading southeast from Nashville to hook up with it.

The railroad went with Stephen Long’s recommendations, and to summarize:

- The town that sprung up at the former site of Ross’s Landing became officially known as Chattanooga.

- Gunter’s Landing later changed its name to Guntersville.

- Terminus changed its name to Marthasville. A few years later, it became known as Atlanta.

Now onto part two of our story:

By the time the Western and Atlantic was being built, engineers and business leaders were already working on the next big thing. A railroad that would connect Nashville to the brand-new town of Chattanooga was granted a charter by the Tennessee General Assembly in 1845. However, it wasn’t obvious what route the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad should take since it would have to cross the Cumberland Plateau and Tennessee River.

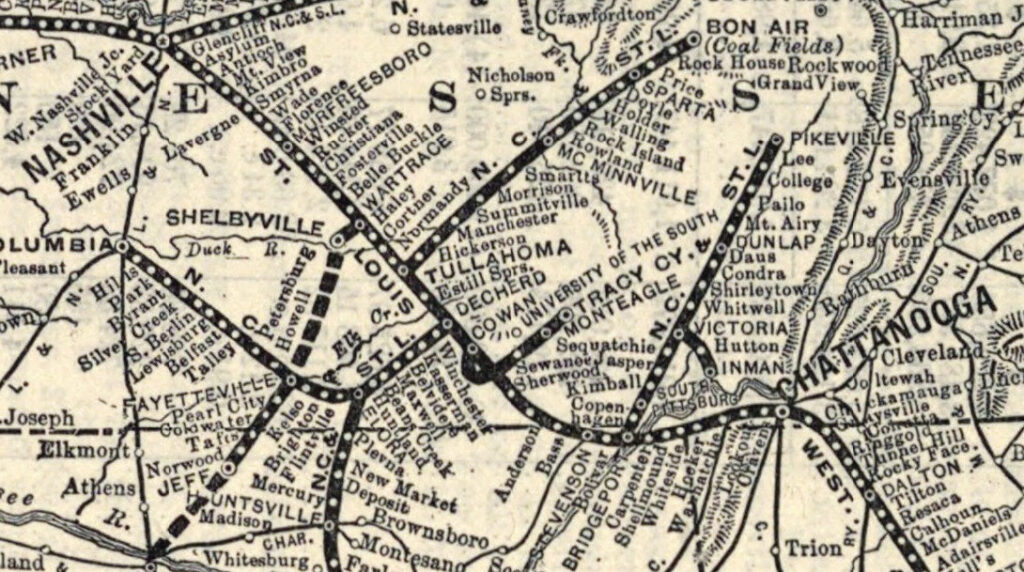

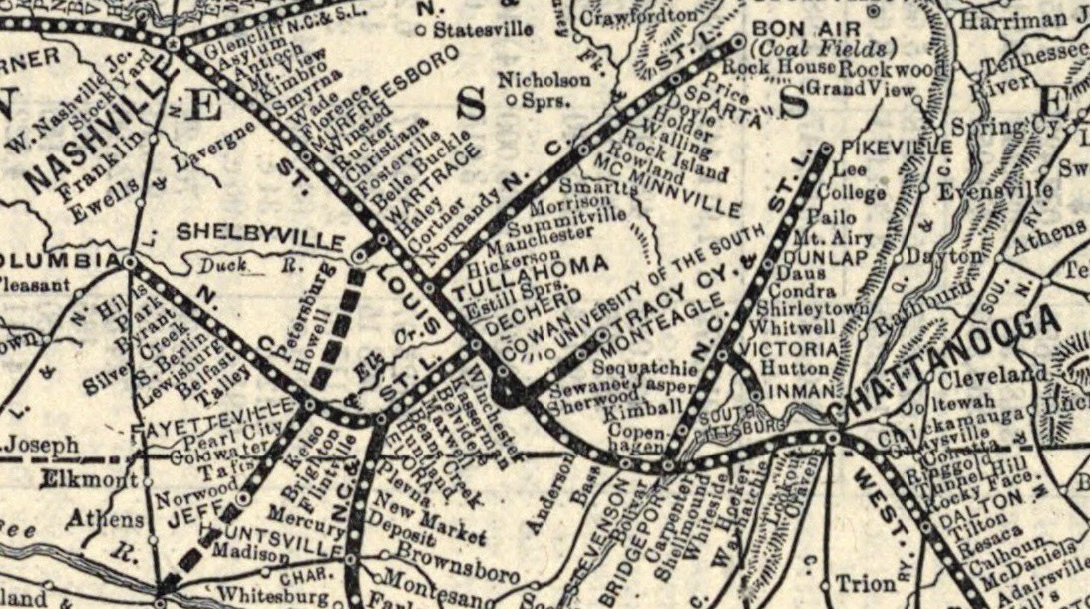

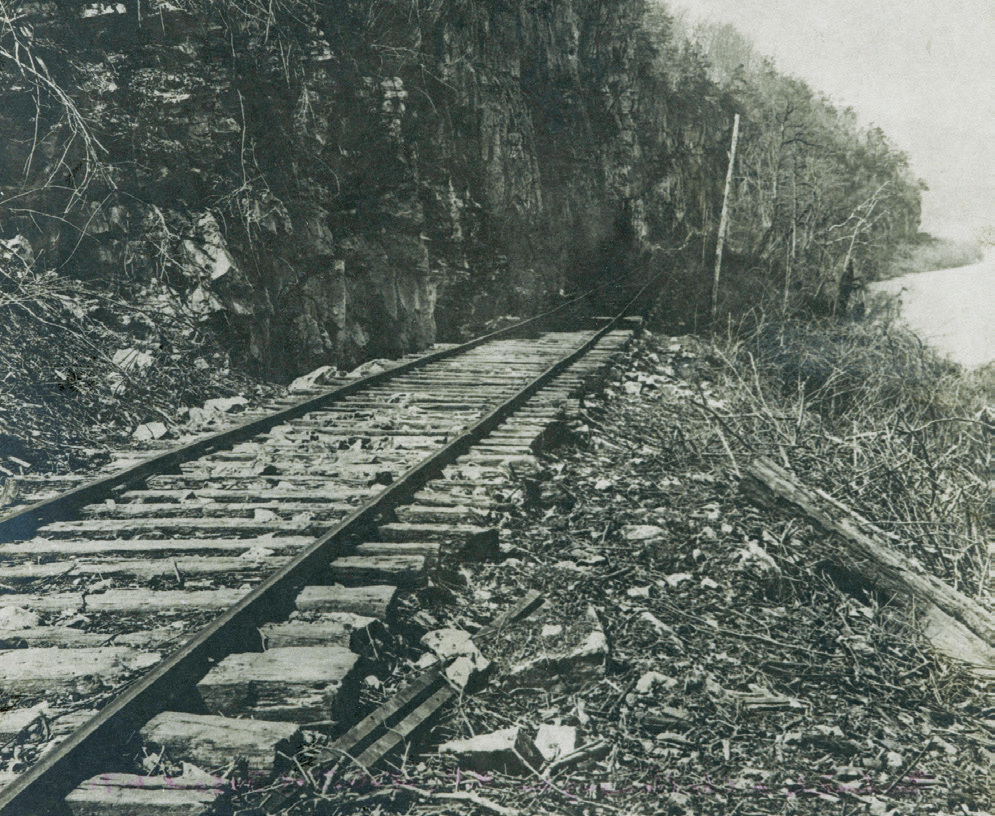

The job fell to another engineer — John Edgar Thomson — who surveyed the route from Nashville to Chattanooga in the summer and fall of 1846. Thomson chose a 152-mile path through Rutherford, Bedford, Coffee and Franklin counties where it would pass through a 2,200 foot tunnel. The railroad would then head into north Alabama, where it turned east at the Tennessee River and headed to Chattanooga from there.

There was a lot of hemming and hawing about Thomson’s route at the time — and not without reason. Murfreesboro was fine with it since the railroad would go right through that town. However, Shelbyville was not. And remember that in 1830, Bedford County had the highest population of any county in Tennessee (30,244) — higher than Davidson and twice the population of Knox.

However, Thomson was simply trying to build a railroad as inexpensively as he could. Having decided the site of the Franklin County tunnel, Thomson decided it made sense for the railroad to cross the Elk River, Duck River and all the gaps in the hills using a path that didn’t go through Shelbyville. His route passed through the Bedford County communities of Wartrace and Bell Buckle — but not Shelbyville, which had to be satisfied with a 10-mile branch line to the Wartrace Depot.

Despite protests from Shelbyville, the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad went with Thomson’s recommendation. And although it wasn’t obvious to everyone at the time, this was a major turning point for Bedford County. After the Civil War, thanks to their status as railroad hubs, Shelby, Davidson, Hamilton and Knox emerged as Tennessee’s most populous counties. But by 1900, Bedford County would fall from first to 19th in population among Tennessee counties.

Shelbyville wasn’t the only town affected by Thomson’s route. A new town called Cowan was surveyed and laid out near where the tunnel was dug. In the 1850s, railroad executives organized two new towns at railroad stops called Tullahoma and Decherd. After the war, other towns along the route such as Smyrna would be incorporated. On the Alabama side of the mountain, both Stevenson and Bridgeport owe their existence to Thomson’s chosen route.

In conclusion, engineers Stephen Harriman Long and John Edgar Thomson had a lot to do with either the existence or the current size of the Tennessee communities of Nashville, Chattanooga, Shelbyville, Murfreesboro, Smyrna, Tullahoma, Decherd and Cowan and the Alabama communities of Guntersville, Stevenson and Bridgeport. However, I’m not sure how much either man reflected on this. Long’s Wikipedia page is dominated by his career as a Western explorer while Thomson is remembered as the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad. So as much as it pains me to admit this, the impact they made to the Tennessee and Alabama maps might have never crossed their minds.