Barrett, Egerton and Seigenthaler informed and inspired us

I’m lucky to have met and befriended some amazing people. Unfortunately, three of them have died in the last year or so: John Egerton, John Seigenthaler and George Barrett. Each was at least a generation older than I. All inspired me and affected the state of Tennessee. With the news of each of their deaths, I was struck both by satisfaction that I had known them at all — and regret that I didn’t know them better.

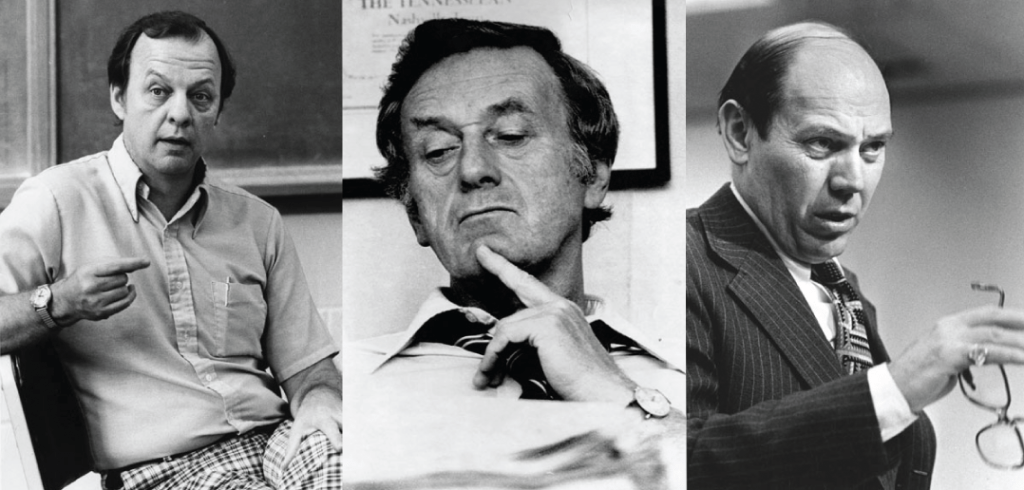

John Egerton died a year ago, in November 2013. In the early 1990s, when I was a reporter, I bought a copy of a Nashville history book titled “Faces of Two Centuries” that John had written years before. Neither a coffee table book nor a scholarly treatise, I could not put this book down the first time I saw it. It was one of the most interesting, detailed, readable and passionate works of local history that I have ever read, and it was one of the books that stoked my interest in Nashville history. In 1999, when I had the opportunity to write a Nashville history book of my own, I wanted it to be as good as “Faces of Two Centuries.”

By the way, John Egerton wrote several other books, the most important of which was “Speak Now Against the Day: The Generation Before the Civil Rights Movement.”

John and I became friends, but not the sort who talk every week. He and I spoke about once a month about the things we were working on. He encouraged me to write books; in fact, he gave me a complimentary review for my first book (and all the reviews weren’t nice — believe me!) He was someone I would frequently call and ask questions about Tennessee history and culture. Two years ago, I wrote a cover story about Nashville history for the (now defunct) Nashville City Paper. The first person I quoted was John Egerton.

What struck me the most about John was the inspirational things he would say and the way he would say them. The last time I saw John Egerton, he and I were at the Nashville Public Library, and he was asking me how Tennessee History for Kids was going. John, who was the sort of person who would invade your body space, shook my hand, pointed his finger right into my chest and said, “Well, you are going to have stick with it, and you know that you are going to have stick with it because if you don’t, no one else will.”

That was the sort of thing he would say to you in his gentle Southern drawl, the kind of thing that wakes you up in the middle of the night with goosebumps. It was the sort of thing that would make you realize, “I can’t quit. John Egerton told me I couldn’t.”

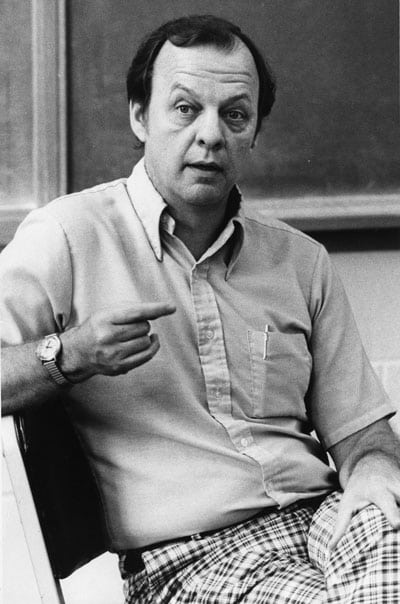

John Seigenthaler, longtime editor of Nashville’s daily newspaper, The Tennessean, died this past summer. I did not know Mr. Seigenthaler well because I worked at the Tennessean after he left. However, he was someone I called upon for stories and advice.

About 10 years ago, for instance, I had an idea for a way the Metro Nashville school system could resuscitate its high school newspapers. I thought this would be a great way to help education and journalism. I must have spent an hour on the phone talking with Mr. Seigenthaler about that idea. (He told me he thought it was a great idea, but, unfortunately, it went nowhere).

In other conversations, I talked to Mr. Seigenthaler about book ideas, politics and Nashville history. I was not of his generation, and I was not his equal, but he always acted as if he thought I was. Back in 2001 as we sat next to each other on an airplane, he told me all about the commission on federal election reform in which he was taking part, but admitted that what he really wanted to do was spend more time with his grandkids.

The last time I saw Mr. Seigenthaler, I showed him a copy of the rare photo I had found of James K. Polk (which was the subject of my November 2013 column in The Tennessee Magazine). Some people might have acted aloof about my discovery of this photo. Not Mr. Seigenthaler, who had written a book about Polk. He was amazed and thrilled and wanted to know all about where I’d found it. As a matter of fact, his reaction made me feel pretty good — an effect he often had on people.

When I wrote “Fortunes, Fiddles and Fried Chicken,” I probably taped five hours of interviews with Mr. Seigenthaler. He was thrilled about the book project and gave me a list of about 25 people he thought I should interview. I think I got around to all of them.

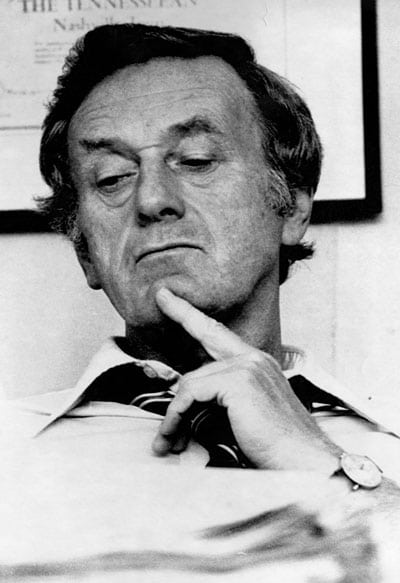

The first time I met George Barrett, he represented me in a lawsuit. You see, George would file lawsuits against the government when he felt like it was overstepping its bounds. In 2000, when I was a reporter at an Internet newspaper called NashvillePost.com, I was kicked out of a secret meeting of the Senate Finance, Ways and Means Committee. A few days later, as a result of this event, George Barrett filed a lawsuit against the state of Tennessee that became known as Mayhew v. Wilder. (My side lost that lawsuit, by the way.)

I got to know George pretty well after that. I learned that he and Cecil Branstetter had been the two Nashville lawyers most associated with organized labor and the civil rights movement back in the 1950s and 1960s. George told me a lot of stories, some of which I have on tape and some of which I have probably already forgotten.

The Highlander Folk School was the topic of my February 2013 column. George had once represented Highlander and its radical leaders (such as Myles Horton), so I had spoken to him about that. About the time the column ran, a statewide movement was formed with a goal to raise money to preserve the Highlander site. This made George very happy. “Hey, you know about these people giving money to save Highlander?” he would say to me.

The last time I ran into George was at the grocery store. We were in the checkout line, and he was talking to me about Highlander and asking me about when we were going to have lunch again. He then turned his attention to the young man who was bagging his groceries. “So who are you?” George asked him. “Where do you go to school?”

The young man told George that he went to Father Ryan High School, the Catholic institution George Barrett attended (along with John Seigenthaler, by the way). Well, that was the end of my conversation with George. He told the kid that he went to Father Ryan and that it is a great school with great tradition. He asked the young man what his plans were, what his favorite subjects were and where he might want to go college. That was where I left George for the last time: treating a young man he had never met as if he were his own son.

Perhaps there is a lot in that story about why I will miss George Barrett, John Seigenthaler and John Egerton.