Immediately after World War II, a pair of nationally publicized riots in Tennessee foreshadowed huge changes that would happen in the United States after the war.

The first took place in Columbia on the night of Feb. 25, 1946. It began when African-American war veteran James Stephenson got in an argument with a clerk in a department store. The men fought, and Stephenson threw the clerk through a window.

That night, a crowd of whites gathered around the Maury County Courthouse, and a crowd of blacks gathered about a block south of there, in a part of town known as Mink Slide. Afraid Stephenson would be lynched, many of the blacks got their guns.

The exact events that took place that night are still in dispute; an author named Robert Ikard delved into them in the 1997 book “No More Social Lynchings.” Many accounts claim that white officials went through the Mink Slide area of Columbia in a foolhardy attempt to “disarm” black citizens there. This led to four white police officers being shot and wounded, which in turn led to a police and “volunteer deputy” sweep through Mink Slide. Doors were kicked open, homes searched and more than 100 African-Americans arrested.

The exact events that took place that night are still in dispute; an author named Robert Ikard delved into them in the 1997 book “No More Social Lynchings.” Many accounts claim that white officials went through the Mink Slide area of Columbia in a foolhardy attempt to “disarm” black citizens there. This led to four white police officers being shot and wounded, which in turn led to a police and “volunteer deputy” sweep through Mink Slide. Doors were kicked open, homes searched and more than 100 African-Americans arrested.

A couple of days later, two of the black prisoners were killed while in custody, allegedly after they grabbed guns from white officers and began shooting at them.

The Mink Slide Riot, as it became known, made national news. The two white police officers were later absolved of any wrongdoing in killing the black prisoners. Two African-Americans found guilty in the shooting of the white officers were later freed while seeking a new trial. One of their defense attorneys was Thurgood Marshall, later the first black member of the U.S. Supreme Court.

“Perhaps the most significant message to come out of the Columbia incident was this: Besieged black citizens had stood up and fought back and lived to tell about it,” author John Egerton concluded in “Speak Now Against the Day: The Generation Before the Civil Rights Movement in the South.”

Six months after the Mink Slide Riot was an election day that’s still famous in Tennessee.

In advance of the election, a group of McMinn County veterans, freshly returned from World War II, formed an organization known as the GI Non-Partisan League. This league nominated some of its own members as candidates to replace people such as incumbent McMinn County Sheriff Pat Mansfield, regarded to be part of the political “machine” that had dominated politics in that county for decades.

Things were tense in Athens when voters went to the polls on Aug. 1, 1946. Sheriff Mansfield was so concerned about the election going against him that he brought in dozens of deputies from other counties to “guard” the polls. Late that afternoon, one of these deputies shot and injured a black man named Tom Gillespie who was trying to vote at the Athens Water Works precinct.

Concerned that he was losing control of the situation, Mansfield called for all ballot boxes to be brought to the county jail so the ballots could be “counted securely,” or so he later claimed.

Members of the GI Non-Partisan League went to the National Guard Armory, armed themselves with semiautomatic weapons and surrounded the jail.

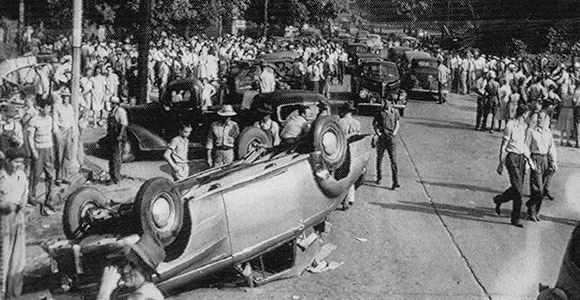

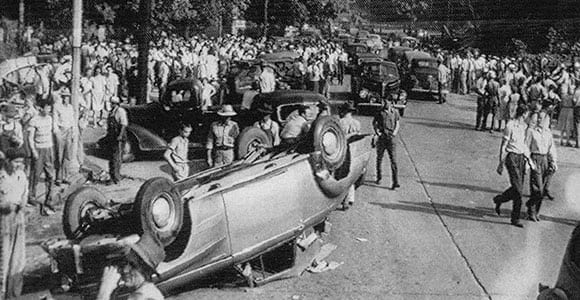

The “Battle of Athens” raged on all night between Mansfield’s men and members of the GI Non-Partisan League. After a shot was fired from somewhere within the jail, some of the GIs began setting off dynamite. Eventually the deputies surrendered the ballot boxes, the votes were counted and all GI candidates were declared victors.

The national media was sympathetic to the cause of the veterans in McMinn County but horrified at the steps taken by them. Today, however, many gun-rights activists are familiar with the Battle of Athens, referring to it as an example of why Americans should have guns.

You can find more information about this event in “The Battle of Athens” by Stephen Byrum.

There’s more on the Web

Go to tnhistoryforkids.org to learn more tales of Tennessee history.