Tennessee likes to boast about old structures it has preserved and historical markers it has erected — especially when it comes to the Civil War. However, in terms of Colonial and Revolutionary War era landmarks, our state doesn’t have such a stellar track record.

The first road across the Cumber-land Plateau connected Kingston (on the east side of the Plateau) to a 19th-century fortress called Fort Blount (on the west side). Thousands of early migrants — some of whose journeys are documented in personal journals and history books — took this road in the 1780s and 1790s.

Spencer’s Rock is found atop an embankment in Cumberland County.

Among the better known of these early migrants were Andrew Jackson, William Blount, Bishop Francis As-bury and French botanist Andre Michaux. However, the most remarkable of all these travelers was a French nobleman who traveled through Tennessee during the French Revolution under the title Louis Philippe, Duke of Orleans. The nephew of Louis XVI, Louis Philippe I later became king of France, ruling from 1830 to 1848.

Today, some people refer to this early road these men travelled on as the Avery Trace or the Holston Road, although it went by many names in its time. I refer to it as the Fort Blount Road.

Around 1795, a new branch of the Fort Blount Road was created that took westward migrants on a more direct route into Middle Tennessee. This branch was created by William Walton and became named for him. The community of Walton started at the westward end of the plateau is known as Carthage.

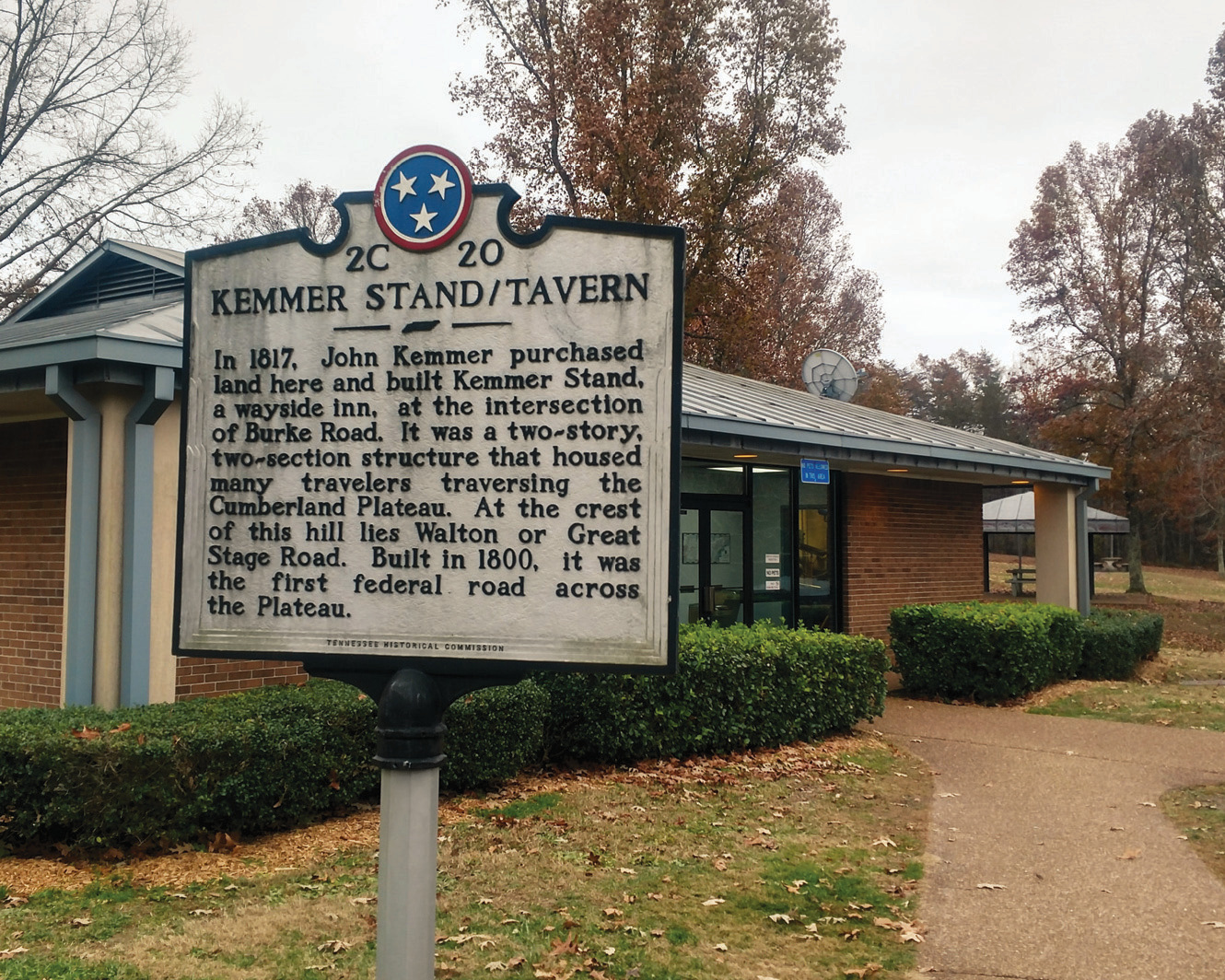

The state of Tennessee has erected a historical marker at a rest area on Interstate 40 to identify the location of Kemmer Stand.

There has been some effort in recent years to generate awareness that this early road existed, especially on its western side. However, there has been no effort to preserve its original roadbeds — at least none that I know of.

No one has done more to learn about the history of the roads than retired Tennessee Tech history professor Calvin Dickinson, who published “The Walton Road: A Nineteenth Century Wilderness Highway in Tennessee” in 2007. After extensive research, Dickinson concluded that the original course of the Fort Blount and Walton roads sometimes follows the present-day course of Highway 70, sometimes follows the present-day course of Interstate 40 and sometimes follows neither of them. Dickinson, my two sons and I recently went searching for remnants of these roadbeds.

Going east to west, here is some of what we found:

- Leaving Kingston, the old road climbed to the top of the Cumber-land Plateau using the general route of Highway 70. In the late 1700s, migrants had a terrible time getting up the mountain here; some of them would apparently carry some of their possessions by hand from the bottom to the top rather than risk taking them up by wagon. As we four ascended the mountain along this highway, we thought we noticed that the old roadbed went off into the woods at times, but we couldn’t be sure. Unfortunately, there aren’t places to stop the car and explore.

- Moving westward, the old road passed by the scenic landmark known as Ozone Falls and into a low point between two mountains near the community of Crab Orchard. For about half a century, an inn here provided the first stopover point for travelers along the old road. On April 1, 1794, Thomas “Big Foot” Spencer was killed near here, which is why a monolith — Spencer’s Rock — that towers over the valley here was named for him. Dr. Dickinson showed us where this rock is; you have to park your car on the westbound side of Interstate 40 and climb a steep embankment to get to it.

- About 10 miles west of Spencer’s Rock, the state has erected a sign at an Interstate rest area that documents the site of Kemmer Tavern, an inn located on the old road. The four of us explored around this rest stop and not only found the remnants of the road bed but even where it crossed Daddys Creek. Much of this is on state property and could (and should) be turned into a historical trail. However, the path is closed to the public, and the old bridge has fallen apart.

- Moving west, the old road bed is hard to follow; Dickinson thinks it meanders back and forth along present-day Interstate 40 and Highway 70. There are two or three places where Dickinson said he found the road bed a quarter-century ago. We drove down a few country roads and residential areas, and he pointed them out to me. Most of the time I had to admit that I never would have noticed them. Also, there were places where Dickinson thought the roadbed had been leveled and destroyed by residential development since he last looked for it.

- In the 1780s and 1790s, just about every traveler along the old road stopped at a place called Flat Rock, which is east of Monterey. Dickinson told me that he had been to Flat Rock before and said it was quite large (as much as 40 feet across). Unfortunately, Flat Rock is on private property, and we thought better of going there without permission.

- As the old road approached Cookeville, it passed by an old homestead called White Plains, which still stands. The old road then went right through present-day Cookeville, missing the Tennessee Tech campus just to the north (although there is nothing whatsoever left of the old roadbed.)

- Descending west from Cookeville in the direction of Carthage, the roadbed follows the general route of Highway 70. A Daughters of the American Revolution marker highlights the location of Raulston Stand, a landmark on the Walton Road whose visitors included Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk and Andrew Johnson. Today, the only thing there is a large tree stump.

A marker placed by the Daughters of the American Revolution highlights the location of Raulston Stand along present-day Highway 70 between Cookeville and Crossville.

Interstate 40 winds below Spencer’s Rock, a monolith in Cumberland County named for Thomas “Big Foot” Spencer.

White Plains, a homestead beside which the Walton Road ran, still stands today.

So what did we conclude after a day of exploring by car and foot? There isn’t much left of the Fort Blount and Walton roads. Landmarks that guided early migrants along its route (Spencer’s Rock and Flat Rock, for instance) are unappreciated and unknown to almost all Tennesseans.

The Volunteer State could — and should — do a better job of documenting and preserving the places and the trails that guided our 19th century era ancestors. They are important parts of Tennessee history and American history. With some effort, the Fort Blount and Walton roads could be turned into historical tourist attractions like the Natchez Trace or Oregon Trail. As it stands, however, the old roadbeds are vanishing — as is our history.