Tennessee history proves that laws about who votes and how they’re allowed to can affect us far into the future

Karen Camper of Memphis is a friend of mine and a board member of Tennessee History for Kids. She’s also a veteran of the U.S. military, which is one reason she and I understand each other.

Karen is also African American and a member of the Tennessee General Assembly. This combination would have been unlikely as recently as 1965, but that was the year President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law.

The reasons this law changed the election of African Americans to the Tennessee State House are fairly hard to explain, but the law made a huge difference. Let me try.

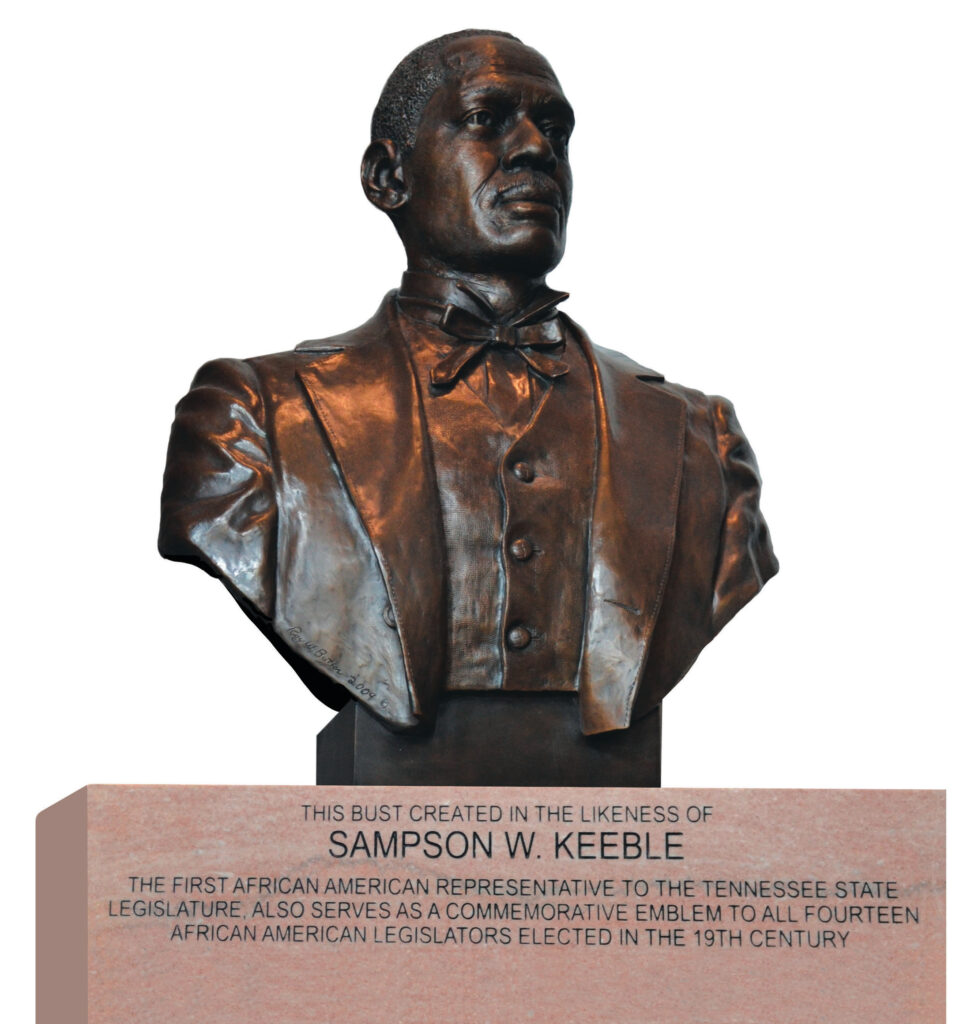

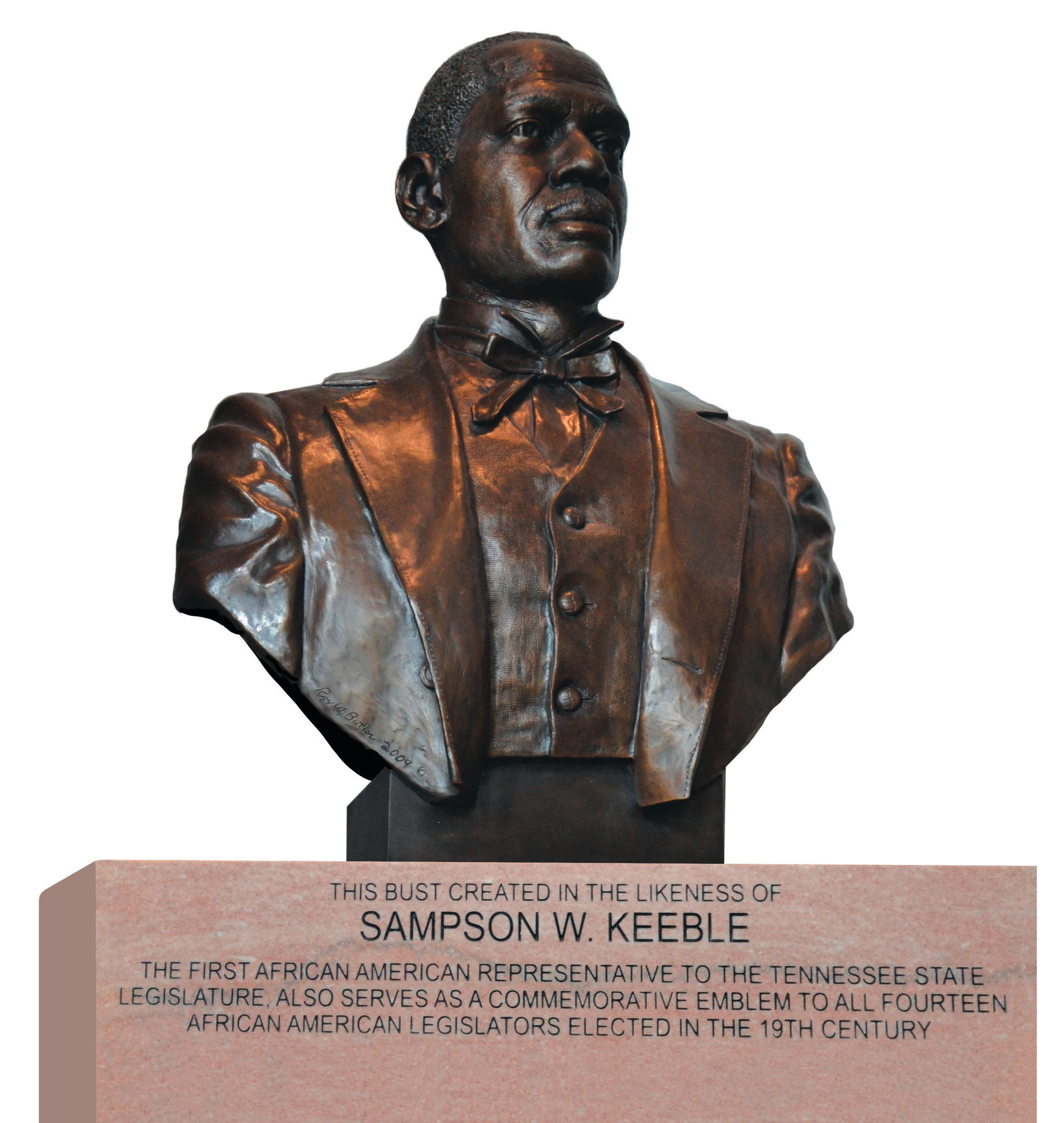

Under the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the right to vote was (theoretically) extended to former slaves. Sampson Keeble, who was born into slavery in Rutherford County, became the first Black man in the General Assembly when he was elected from Davidson County in 1872.

During the next two decades, 13 more African Americans were elected to the Tennessee State House. Among them were Thomas Cassels of Shelby County, the attorney who represented Ida B. Wells in her lawsuit against the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad, and Samuel McElwee of Haywood County, who was re-elected multiple times.

However, by 1890, voting laws were changed, “purifying” Tennessee’s ballot box (in the vernacular of the news media and several generations of Tennessee history textbooks). As I understand it, these laws fall into three categories.

The best-known of these changes was a tax on voting, known as the poll tax. The poll tax was authorized by the Tennessee Constitution of 1870 but was not put in place until 1889. At a time when Tennessee had no sales tax, the poll tax was an important revenue measure that raised money for public schools. It also had the (fully intended) effect of discouraging poor people (Black and white) from voting.

A second change was known as the Dortch Law when it was first passed in 1889, although it would be altered and tweaked many times over the years. This infamous piece of legislation was named for State Rep. Josiah Dortch of Fayette County (one of the first graduates of Nashville’s Vanderbilt University, by the way). The Dortch Law effectively required a voter to be able to read a ballot, as opposed to turning in a ballot that had already been filled out for the voter (which had been the case prior to that time). Furthermore, in its original version, the Dortch Law allowed poll workers to help white voters read their ballots but not Black voters.

This bust of Rep. Sampson Keeble sits in the rotunda of the Tennessee State Capitol

The Dortch Law explains why early civil rights workers (trained in places such as the Highlander Folk School) spent so much time teaching people how to read. After all, a person who couldn’t read couldn’t vote. The idea behind the Dortch Law also illustrates why literacy is a very empowering skill.

However, as important as the poll tax and Dortch laws were, I’ve become convinced that the third change to voting laws in 1889 was the most important of all. It had to do with the way district lines were drawn in heavily popu lated counties such as Shelby and Davidson.

In the 1880s, Shelby and Davidson counties had larger numbers of African American residents. Each also had enough people to justify several House districts, and in the 1880s, each county had about five or six separate districts (much like each county has multiple House districts today).

However, in 1889, the General Assembly passed a bill that allowed both Shelby and Davidson counties to get rid of their separate geographic districts and, instead, to lump all of their districts together into county-wide “multi-member” districts. So, instead of having separate House districts, both counties were represented by people elected “at large” by the entire county.

The logic of this is pretty clear in hindsight. With Davidson and Shelby counties divided into separate geographic districts, it was inevitable that one or more of those districts would be majority Black and would, therefore, elect an African American representative. But if those counties elected a “ticket” of House members at large, it would be very unlikely that an African American would win.

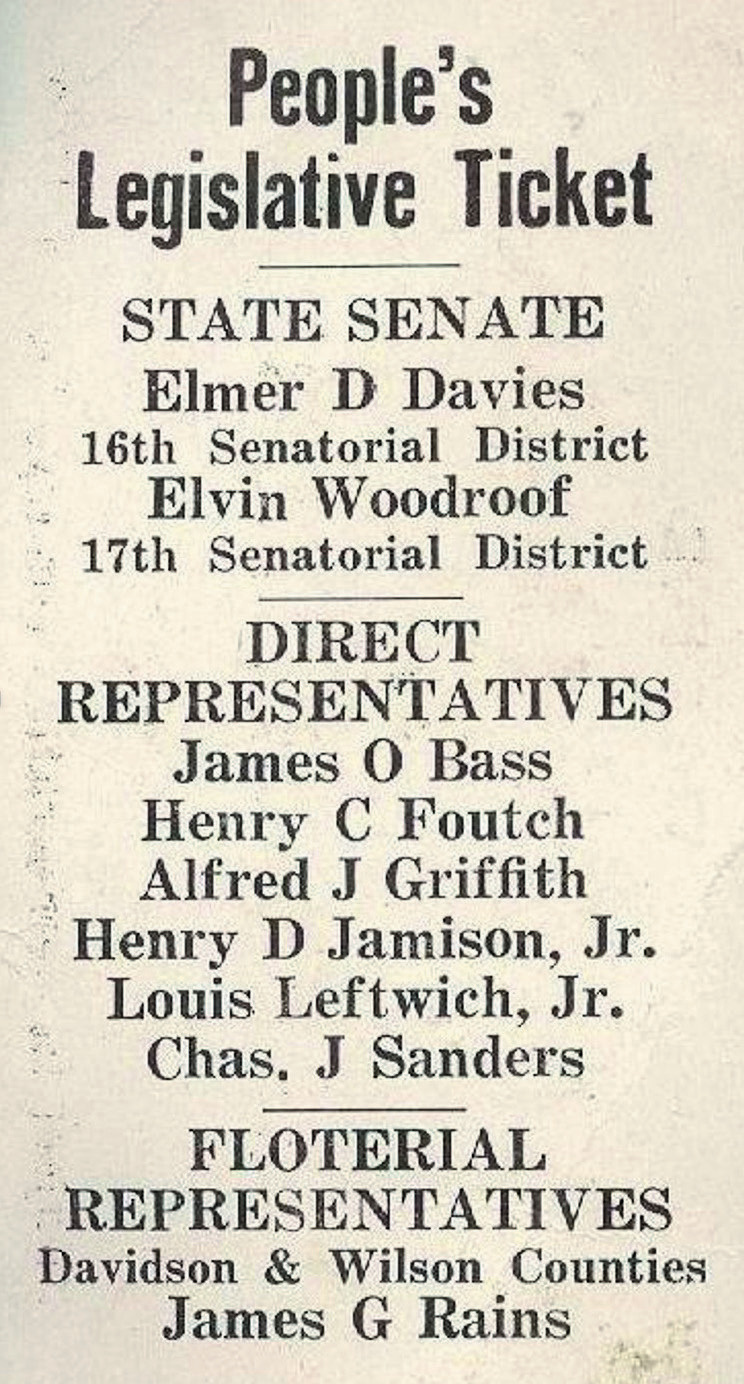

Under a system that replaced separate geographic districts with county-wide “multi-member” districts in Shelby and Davidson counties, establishment groups chose “tickets” of men who campaigned together.

Thanks to this system, neither Davidson nor Shelby County elected an African American to the General Assembly for three-quarters of a century. Typically, the way it worked was that the Democratic Party establishment, chamber of commerce and newspaper editors got together and chose a “ticket” of a half-dozen men who campaigned together (although there wasn’t much campaigning that needed to be done under this system).

In 1964, on the eve of the passage of the national voting rights act, A.W. Willis of Shelby County was elected as one of Shelby County’s representatives. In 1965, he was the only Black member of the 99-member Tennessee House.

There are many parts of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the many state laws that were passed because of it probably fill quite a few law school lectures. As a result of the national law, Tennessee got rid of the “multi-member” districts in Shelby and Davidson counties and created separate districts. That’s why there were six African American House members elected in November 1966 (three from Shelby County, two from Davidson and one from Knox). At least one of these six members of the “Class of ’66” is still alive, that being Bob Booker of Knoxville, who writes and speaks about various subject as part of the Knoxville History Project (knoxvillehistoryproject.com).