Tennessee towns didn’t just “happen.” They were founded by investors who pooled their money, sent surveyors to find the most strategic locations, bought and subdivided hundreds of acres and laid out town squares, roads and lots. These investors also bought advertisements that made their communities sound like the best places to live.

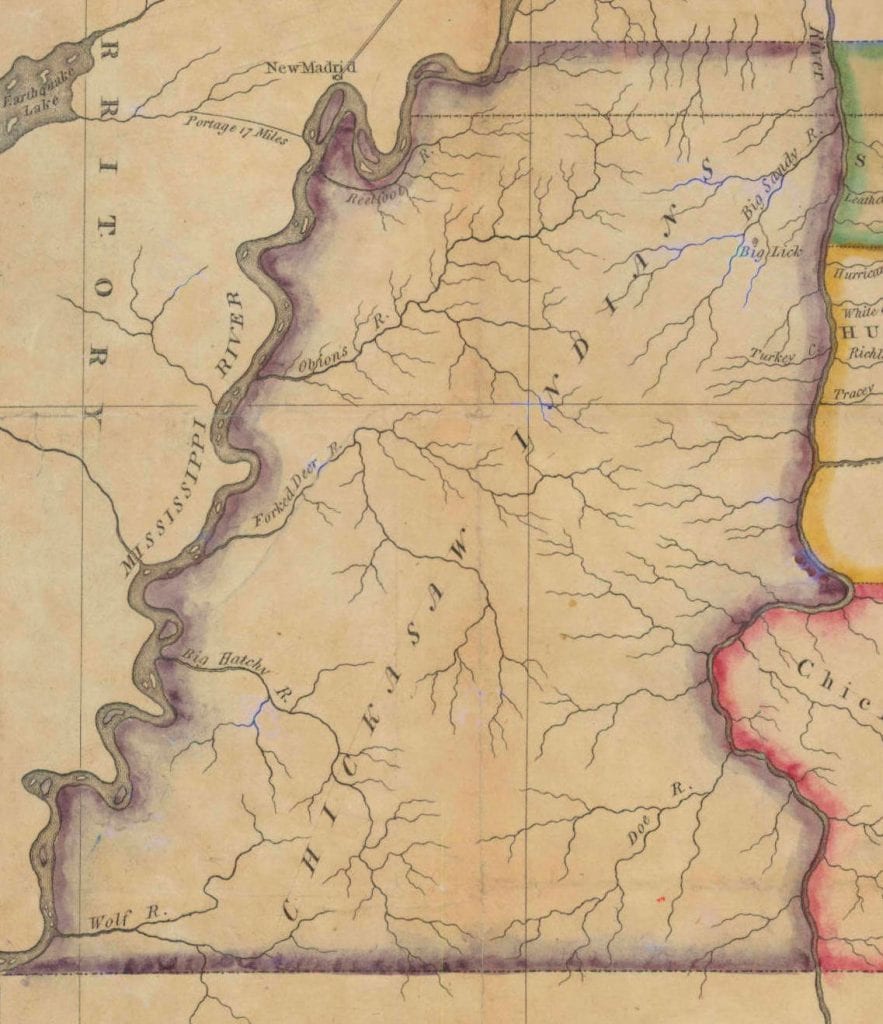

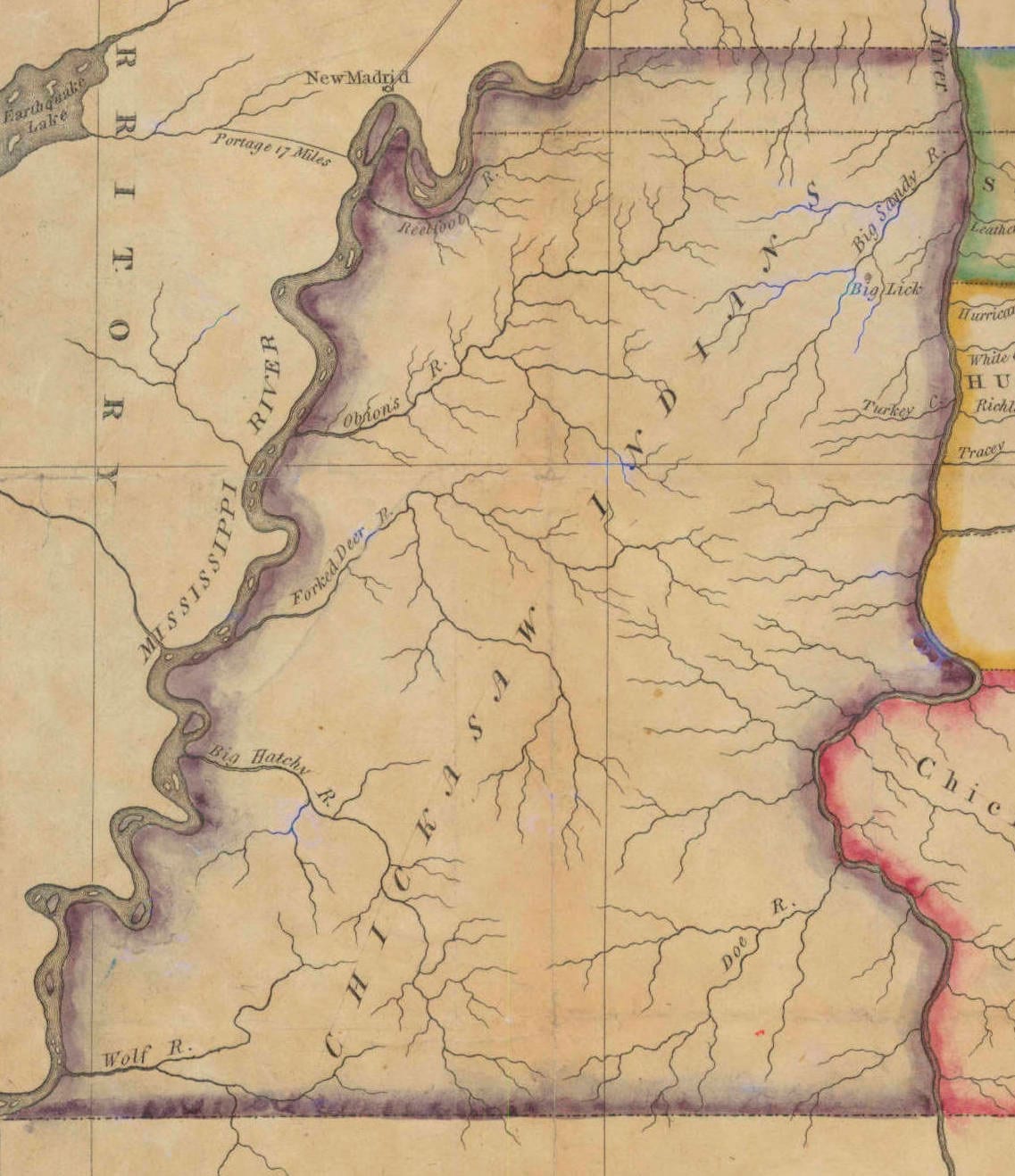

After the War of 1812, the U.S. government bought land west of the Tennessee River and east of the Mississippi River from the Chickasaw Indian nation. Andrew Jackson represented the U.S. government in this 1818 transaction, which newspapers of that era referred to as the Chickasaw Purchase. After it occurred, the Chickasaw Indians were forced to move to present-day Mississippi.

White settlers moved quickly into West Tennessee, creating one of America’s first land rushes. They organized towns with speed — a process documented in newspapers of the time.

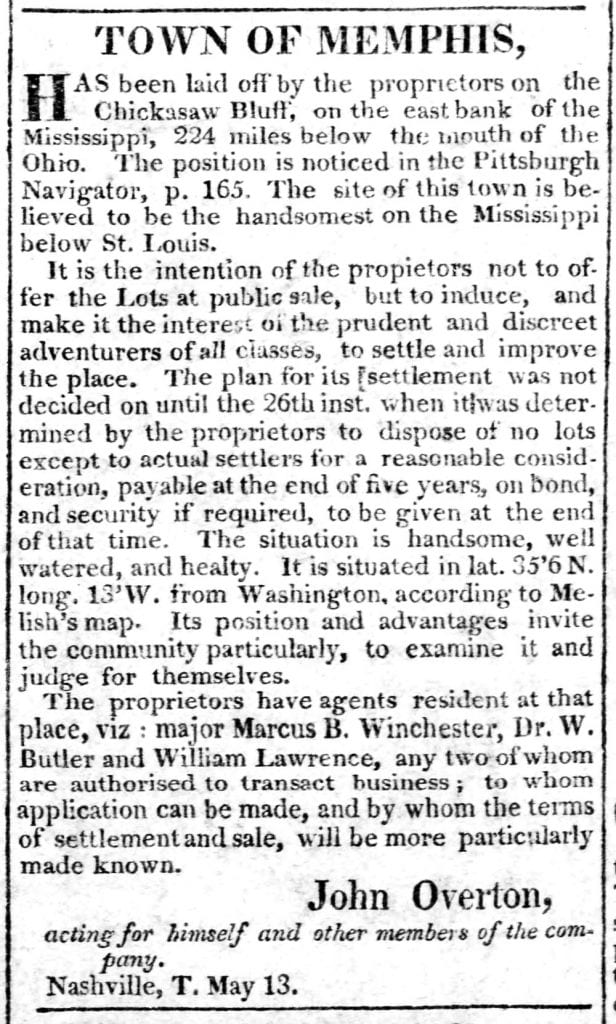

“(The) town of Memphis has been laid off by the proprietors on the Chickasaw Bluff, on the east bank of the Mississippi, 224 miles below the mouth of the Ohio,” reported the July 3, 1820, Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette. “The site of this town is believed to be the handsomest on the Mississippi below St. Louis.”

The Jackson Gazette contained ads for many of the other towns that were laid out in the decade following the Chickasaw Purchase. Here are some examples:

“On Monday the 20th of September next, the Commissioners of the town of Lexington will proceed to sell the balance of the LOTS remaining unsold in said town,” the paper reported on Aug. 24, 1824.

“Among the many towns about to be reared in the Western District, none presents greater claims to public consideration than the town of Covington,” claimed an ad on Feb. 12, 1825. “Few towns in the state possess equal advantages in a commercial point of view.”

“Taking everything into view, we feel ourselves authorized in saying the town of Dresden presents to the purchaser many advantages, and has a fair prospect to become wealthy, respectable and populous,” said an ad on Feb. 19, 1825.

“This town (Gibson-Port — later Trenton) is situated on a beautiful eminence, or bluff, on the South side of the Little North Fork of Forked-Deer River, in the centre of a county in point of soil not surpassed by any in the Western District,” the Gazette published on June 11, 1825. “Adjacent to the town are four never-failing Springs, of excellent water.”

“We believe few town sites in the Western country will present to the consideration of the people superior claims (than that of Dyersburg),” said an ad on July 9, 1825.

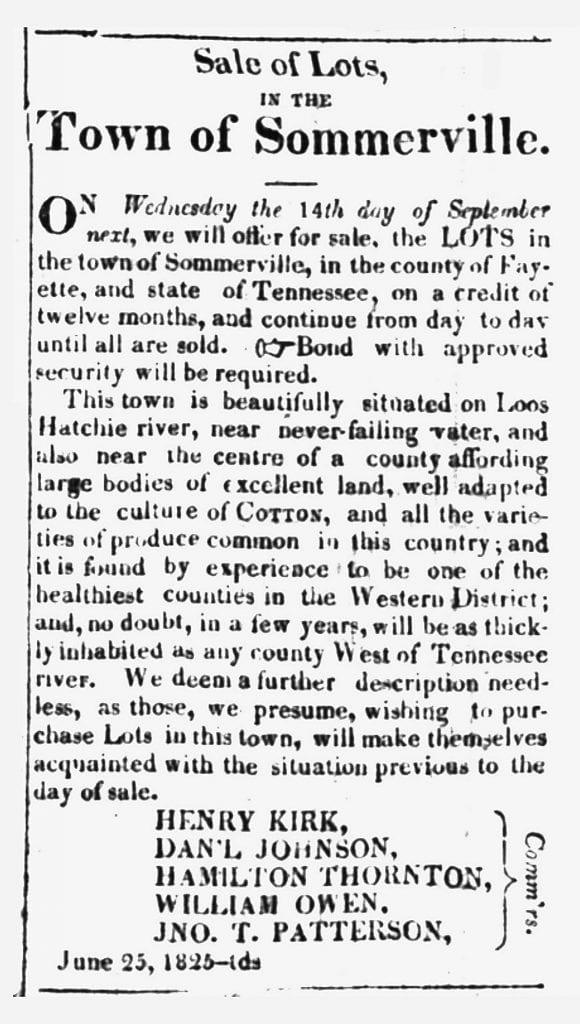

“This town (Sommerville — later spelled Somerville) is beautifully situated on Loos Hatchie river, near never-failing water, and also near the centre of a county affording large bodies of excellent land,” said an ad in the Gazette on July 9, 1825.

Most of these towns remain today. However, the Memphis Advertiser ran ads for a Tipton County community called Randolph in the fall of 1827. Located on the Mississippi River about 40 miles upstream from Memphis, Randolph had hotels, a newspaper and a thriving cotton trade within only a few years. Today you can still read back issues of the Randolph Recorder newspaper, published in the 1830s, at the Tennessee State Library and Archives.

However, from its early years, Randolph was doomed. An 1834 cholera epidemic was so bad that, as the Nashville newspaper reported, “It was with great difficulty that coffins, even of the coarsest material, could be procured to bury the dead — so sudden and fatal were the attacks.” Randolph later lost out to Memphis for the U.S. mail route and the railroads.

Today there is little left of the town of Randolph.