The Volunteer State was affected indirectly but felt the effects for a very long time

Last month, on the 100th anniversary of the U.S. joining World War I, I wrote about some of the Tennesseans who fought in the war. This month, I’d like to talk about the ways World War I affected the homefront.

I’ll begin by saying that, in my opinion, World War I had more long-term impact on Tennessee than any other war in the 20th century. If this statement surprises you, then consider these four examples:

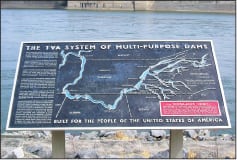

Wilson Dam

Prior to the creation of dams, the Tennessee River was unnavigable in the Muscle Shoals area in northwest Alabama. Many of Tennessee’s early settlers learned this when they migrated west aboard flatboats and wrecked or got stuck there.

Attempts to solve the Muscle Shoals problem began as early as the 1830s when the federal government tried (and failed) to build a canal around them.

About the time the U.S. entered World War I, the federal government began building a dam on the Tennessee River in northwest Alabama. Its primary purpose was to provide power so the government could make gunpowder for the U.S. Army. The dam brought with it the added bonus of flooding the Muscle Shoals, making the Tennessee River passable through north Alabama.

Wilson Dam, as it became known, wasn’t finished until long after the war ended. What followed was a long debate about what to do with it. At one point, the federal government considered selling the dam to Henry Ford, who intended to build a massive industrial city in the area that would rival Detroit. The Tennessee Manufacturers Association, precursor to the Tennessee Chamber of Commerce and Industry, sent lobbyists to Washington, D.C., to build support for this idea.

The proposal to sell the dam to Ford was rejected because people like Sen. George Norris of Nebraska thought the government should not turn over Wilson Dam to a private individual. What they preferred was a quasi-governmental organization that would build dams up and down the Tennessee River. Under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, this idea morphed into the Tennessee Valley Authority.

Today, TVA operates hydroelectric, coal, natural gas and nuclear power plants — as well as renewable energy sites — all over the Tennessee Valley. It provides electricity, which affects the lives of just about everyone in the state. People fish and play on TVA lakes. Towboats and barges routinely carry products from one end of the Tennessee River to the other because it has been made permanently navigable. Thanks to TVA and its network of dams, rivers in Tennessee are far less likely to flood as they once were.

I think it is sad that TVA caused the flooding of thousands of homes, farms and communities in Tennessee. But there is no doubt that it has changed the state forever. It all started because of World War I.

Old Hickory

This story has a lot in common with Wilson Dam. In 1918, the federal government authorized DuPont to build a gunpowder factory at a bend in the Cumberland River northeast of Nashville known as Jacksonville. Like Wilson Dam, the construction of the Jacksonville powder plant was a massive undertaking that resulted in a migration of thousands of people. The plant went into production in July 1918 and within a few months was producing 700,000 pounds of smokeless powder per day.

But after the war ended, the federal government closed down Old Hickory. For several years, the facility sat idle. Eventually, DuPont bought the factory it had built only a few years earlier for a fraction of the cost it had been paid to build it. About that time, Jacksonville changed its name to Old Hickory.

DuPont thus became one of the largest industrial employers in Middle Tennessee and remained so until recent times.

Naval Air Station Memphis

When I flew in the Navy, I knew many people who had been trained at a naval air station near Memphis. What I didn’t realize until recently was that this facility (now known as Naval Support Activity Mid-South) was first created because of World War I.

It was 100 years ago this month that the Department of War sent a group of officers to Memphis to find a site for a military aviation school. They chose the Millington area, and by the end of that summer, the new school was known as Park Field. During the war, thousands of U.S. aviators learned how to fly Curtiss JN-4 Jennys in the air above Millington.

Park Field shut down in the 1920s but came back during World War II, this time under the name Naval Air Station Memphis. For decades, it was a place where enlisted aircrewmen went for flight training. That changed in the 1990s. Although aviators are no longer trained at Millington, it remains a navy base today and is used for functions such as human resources and personnel command.

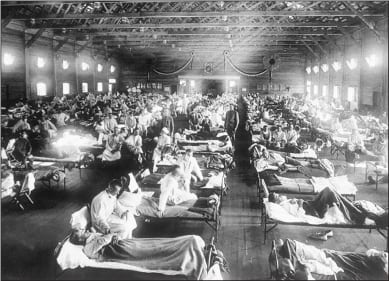

The influenza epidemic

No one knows for sure how the influenza epidemic of 1918 started. But the mass migration of people during the war and the horrible living conditions the war caused in some parts of the world absolutely contributed to its spread.

The epidemic killed far more people than World War I. Some 8,000 Tennesseans died from the epidemic — more than twice the number who died in the war itself.

In Tennessee, influenza hit densely populated places especially hard. For several weeks, just about everyone who ventured outside in one of Tennessee’s cities wore a mask. Church services were canceled for weeks. So was college football season (heaven forbid!).

However, the epidemic’s biggest impact on Tennessee may have been more long-term.

The influenza epidemic resulted in reform within the medical community. In part because of the epidemic, national foundations such as the General Education Board began giving more money to the cause of medical education. They also became very critical of the type of medical education then being given at small medical colleges all over America. As a result, small medical colleges across Tennessee were shut down while the ones at Vanderbilt and Meharry (in Nashville) were greatly expanded. This type of reform took place throughout the country, affecting medical education nationwide and contributing to the “professionalization” of the medical field.

So, today, when you use electricity, drive by Old Hickory or the naval base at Millington and visit a hospital, think about the Great War of 1918 and how it changed your life.