It can be hard to pin down exactly when a place became a major tourist attraction, but I recently discovered the month and year it happened to Gatlinburg.

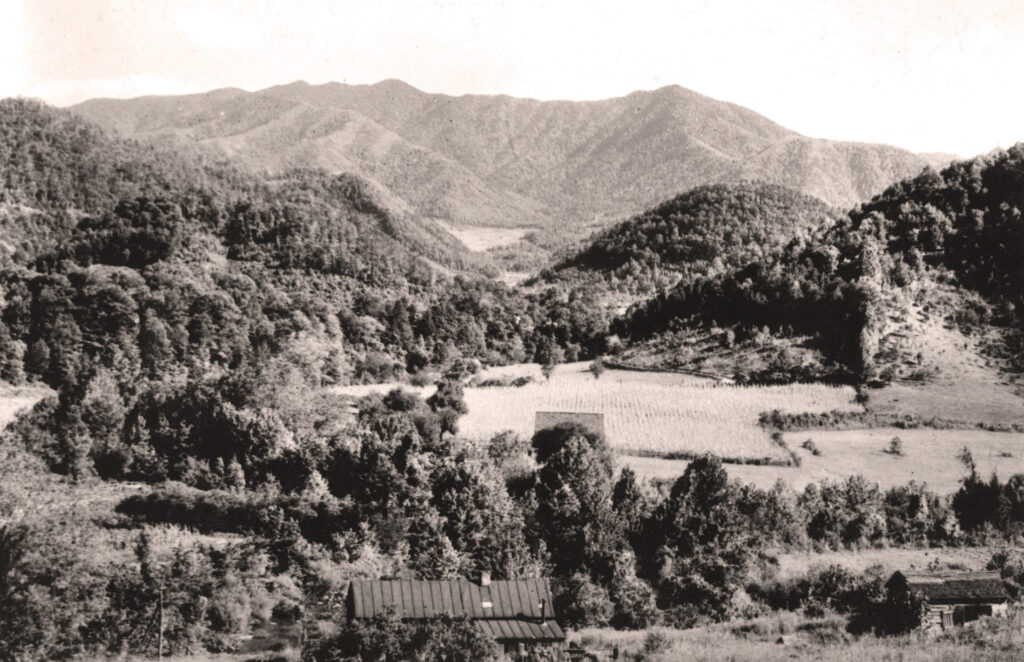

In the early part of the 20th century, not many people visited Gatlinburg because it was so hard to get there. The road that led from Knoxville to Gatlinburg was a dirt path south of Sevierville. It was in such bad condition that the few people who had cars were reluctant to risk the drive.

In August 1920, an apple farmer named H.H. Oakley made the occasional journey from Gatlinburg in a wagon led by mules. “It takes him a day and a half to get here and the same time to return home,” the Knoxville Sentinel said.

Around that time, a reporter drove the route and had this to say about it: “From Sevierville we wound thru the mountains to Gatlinburg, being compelled to wait until the car ahead of us had passed over bridges, lest the rickety things might give way.”

In 1924, the biggest story out of Gatlinburg was when a man named Matt Ogle shot and killed Henry Owenby in an argument connected to a moonshine still. The news item about the crime spoke volumes about what the town consisted of at that time. “The shooting occurred on the store porch at Gatlinburg Wednesday afternoon,” reported the article. In other words, Gatlinburg had at least one still — and only one “store porch.”

The movement to turn the Smoky Mountains into a national park was turning the corner by this time, so it was obvious that the Sevierville-to-Gatlinburg road would be improved as part of Gov. Austin Peay’s road-building plan. However, the event that immediately caused the road to be hurried along took place about a hundred miles to the south.

In July 1925, national attention focused on Dayton and the trial between the state of Tennessee and substitute teacher John Scopes. To encourage the people attending the trial to visit the proposed national park, the new Tennessee Highway Department rushed to pave the road between Pigeon Forge and Gatlinburg. “The improvements were ordered on account of the visit expected to be made by the scientists, visitors and attorneys in the Scopes trial at Dayton, to the proposed national park area in the Great Smokies,” the Knoxville Journal reported on July 19, 1925.

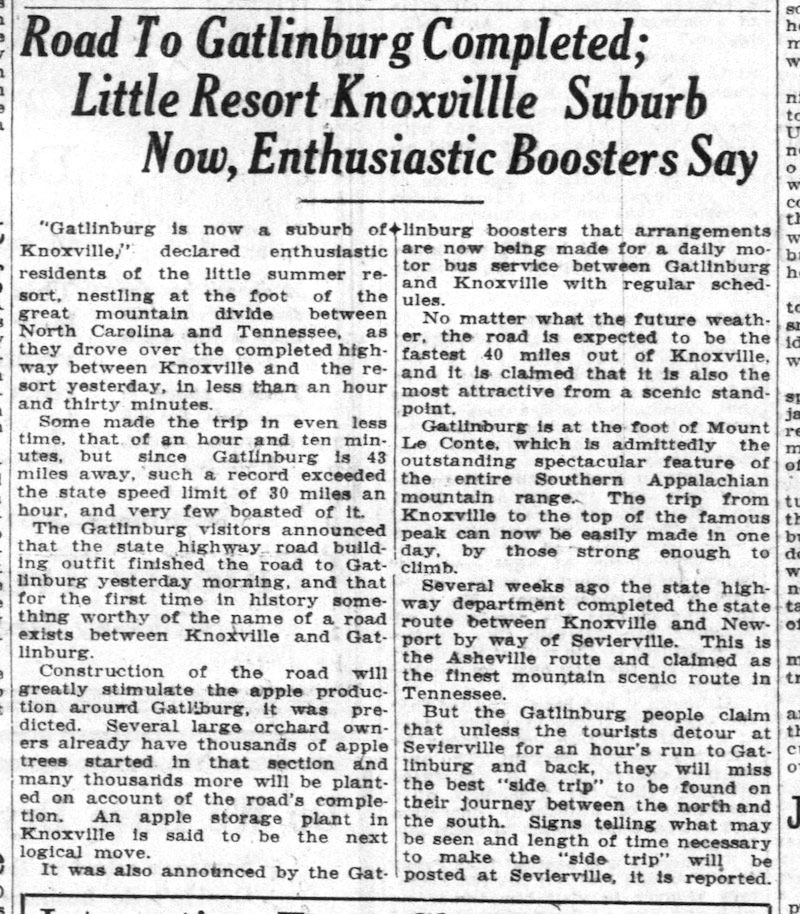

So it was that, in July 1925, a road crew of about 40 men blasted rocks, widened and leveled the bed, and paved the road along the Little Pigeon River in Sevier County. They made such progress that, on Aug. 8, the Journal declared that “for the first time in history something worthy of the name of a road exists between Knoxville and Gatlinburg.”

Overnight, Gatlinburg went from a difficult-to-reach mountain village to a tourist destination. “‘Gatlinburg is now a suburb of Knoxville,’ declared enthusiastic residents of the little summer resort, nestling at the foot of the great mountain divide between North Carolina and Tennessee,” the Journal reported. Within weeks, the paper was filled with small items about families, church groups, Boy Scout troops and others visiting the place.

A year after the road was improved, a YMCA official named Barnett Napier stationed boys along the road between Pigeon Forge and Gatlinburg and instructed them to count cars. The findings? “Gatlinburg was visited by 510 cars last Sunday afternoon between the hours of 1 and 5 p.m,” the Journal reported on July 1, 1926. “Not more than 10 cars visited Gatlinburg on Sunday afternoon two years ago.”

The word “Gatlinburg” only appeared 11 times in Knoxville’s two daily newspapers in 1920. It was mentioned 180 times in 1925 and 227 times in 1926.

During the next few years, some of the stories published nationally about Gatlinburg made it sound like outsiders had found aliens from another planet. “It is only very recently that the children of the western Smokies have learned to play,” a travel writer for the Oakland (California) Tribune wrote in 1928. “Because of their shut-in existence the mountain people did not show their feelings and their children were sombre-looking little things who did not smile and laugh like ordinary children.” However, the article went on to say, “most of those same solemn faced boys and girls now know how to sing, run and play and laugh.” The once-remote Gatlinburg “now boasts a fine new church, two excellent summer hotels, many new homes, three general stores, a barber’s shop, two small gift shops, and two antique shops.”

Gatlinburg’s first two hotels were the Mountain View Hotel (built by Andy Huff in 1919) and the Riverside Hotel (built by Dick Whaley in 1923). In the 1920s and for some years after that, these hotels reflected a different culture and lifestyle than we experience today. Their rooms had porches, rocking chairs and (of course) no air conditioning. Guests at the Mountain View Hotel hiked all day and sat down at family-style tables to dinners of fried chicken, boiled ham, creamed potatoes and fresh (but overcooked) vegetables.

After the road was paved, Huff and Whaley added new rooms and built new hotels. And I think it is safe to say that they and others like them haven’t stopped building hotel rooms in Gatlinburg since.

Finally, a personal note: Among the many Knoxville residents who made day trips to Gatlinburg during these early years was my grandmother, who graduated from Knoxville High School the same year the road was paved. Louise Dempsey liked the place so much that she moved into a small apartment there after she was widowed, which is why I spent so much of my teenage years there.

The following realization is staggering for me to contemplate:

When I was wandering around Gatlinburg in 1974 — going to the Space Needle and Wax Museum and playing putt-putt golf — the year 1925 was as far removed (49 years) as the year 1974 is now. As much as Gatlinburg has changed in the last half century, it changed far more in the previous half century.